A river flows under Atlanta’s airport, and people hope to make it a destination

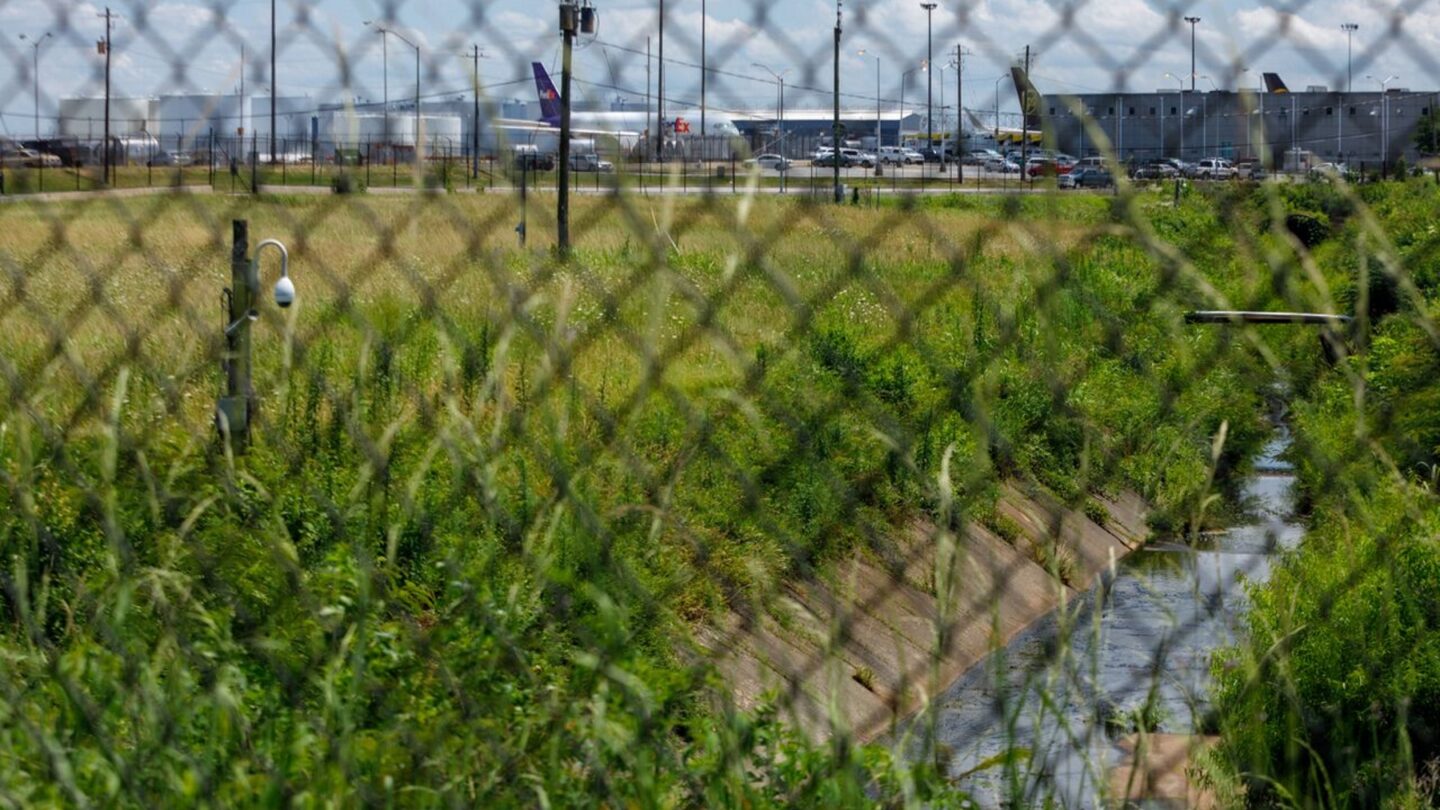

South of the airport, the Flint River gains in size and flows above ground. The lights for the fifth runway are in the background.

Dustin Chambers / WABE

When you’re in a plane on the runway at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport, or on the plane train heading to a terminal, the Flint River might be flowing somewhere beneath you.

The river starts just north of the airport, and it’s not really much to see around its headwaters, woven into the cities through which it flows, through pipes and in ditches along roads.

There’s an initiative now to bring the Flint out of its relative obscurity in the Atlanta area and to make the river a destination.

Finding The River

Hannah Palmer grew up near the airport, in houses that have since been bulldozed as the airport has grown. As a kid, she says, she had a vague idea the Flint River existed but didn’t realize it flowed near her.

Now, she’s on a mission to let people around the airport know the Flint River is a thing, and it’s here.

“I’ve been doing this tour,” she says, “just taking community groups around who literally have never heard of the Flint River, never seen it.”

Palmer works for an initiative called Finding the Flint, funded by the Atlanta Regional Commission and the environmental groups American Rivers and the Conservation Fund.

She starts the tour in Hapeville, and, warning that the river might look a little underwhelming, sets off for the headwaters.

“It’s not like you go to the source of the Ganges in the Himalayas or some sacred mountain pristine place,” she says. “This is a totally urbanized watershed.”

As she crosses into East Point, she points out a dense bunch of trees off the side of the road, a sign that water is nearby. She says she’s used maps, plus clues like the trees, to piece together where the Flint flows.

“It’s like a scavenger hunt,” Palmer says.

In a semi-industrial area in East Point near an electrical substation, she pulls over for the first stop of her tour. Here, the Flint River is a stream of water in a ditch by the side of the road.

And, like the water in any other ditch, it’s heading somewhere. The water here will tunnel under the airport, flow through Middle and South Georgia, meet up with the Chattahoochee River at the Florida border, form the Apalachicola River and empty into the Gulf of Mexico. It supplies water to farms, cities, wildlife and fish. It’s tied up in a U.S. Supreme Court case.

Connecting To The River

The idea with the Finding the Flint project is to connect people with the river in different ways, depending on location. Near the electrical substation, Palmer says, the tactic could be to just add a sidewalk along the road and a sign pointing out that the ditch is a river.

In other places, though, Palmer has bigger ambitions.

Outside a fence around the airport, near Delta’s flight museum and headquarters, the Flint River heads underground for about a mile and a half (though it does have a moment of daylight between runways).

“From where we’re standing, you can see planes taking off, you can hear the activity of the runways,” Palmer says.

There’s open space inside the fence right along the river, just before it goes underground. Palmer says she’d like to see a little park here, a place for airport employees or travelers to enjoy some nature and for people to come watch the planes.

“I have two little kids who love watching planes and who demand to do so, quite often,” she says, as a plane roars overhead. “We have the world’s busiest airport; we don’t have an official observation deck. I love the idea of using the river as a way to create that public interface.”

So this idea of improving the Flint River and adding trails and parks around the airport – what does the airport think of all this?

“We think it’s a great idea,” says Polly Sattler, senior sustainability planner at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport.

Sattler, who is also on the board of the Flint Riverkeeper, one of more than a dozen organizations that support Finding the Flint, says the initiative could actually be good for the airport because it could help manage all the water that flows off the runways during storms.

Though, she adds, there are some things to figure out, like security around the airport and making sure the river doesn’t attract more birds, since those don’t mix well with planes.

“So there are complications,” she says.

Delta Air Lines supports the project, too, as do the cities of East Point, College Park and Hapeville.

“Bringing awareness to an amenity that has been hidden for so many years is really important for the area, for quality of life, for recreation,” says Kirsten Mote, the program director with the Aerotropolis CID, another project supporter.

Highlighting Rivers

Finding the Flint is one of several projects in metro Atlanta where people are working to take advantage of the creeks and streams that run through the region. In addition to the Chattahoochee, there are efforts on Proctor Creek on the city’s west side; on Peachtree Creek in northeast Atlanta; and on the South River in DeKalb County.

“It’s an interesting space we’re getting into in metro Atlanta where we’re realizing the value of these watersheds,” says Katherine Zitsch, manager of natural resources at the Atlanta Regional Commission. “It’s a conversation that is going on across the region about getting people access to these phenomenal recreational features while also restoring them along the way.”

Other cities have been rediscovering their rivers or waterfronts, too: Austin, Texas; New York; Los Angeles.

There is a huge revitalization project on the LA River, for example, which would be familiar, perhaps, to fans of the movies “Grease,” “Terminator 2” or “Drive,” as a large concrete trench.

“If they can do it there, we can do it here with these little headwaters,” says Palmer.

Enjoying The River

South of the airport, once the river is above ground again, the Flint looks like a river, and it’s pretty.

“It is surprising how beautiful the river is down here,” Palmer says.

She’s standing under a bridge, so it’s not like total wilderness, but here, the Flint is about 30 feet wide. Instead of being in a ditch, the river flows around rocks and has actual riverbanks, with tall grass and flowers growing along them.

Looking back upstream, we can see the approach lights of the airport’s fifth runway.

Maybe someday there could be a larger regional park here, Palmer says.

She’s raising her family in this area and says she’d like to bring her kids to play along the river, a big difference from when she was growing up and didn’t know where the Flint River was.