Atlanta Subdivision Forgotten, Stuck In The Recession

Atlanta’s housing market seems to be back. Condos and apartments are shooting up, and there are plenty of construction cranes around the city. But those cranes aren’t everywhere. Across the metro area, there are hundreds of subdivisions still showing signs of the Great Recession.

‘All These Nice Big Houses, But … ’

From the outside, the Villages at Oakshire, in the southeast corner of Atlanta, looks like a neat, normal housing development. Big brick walls flank the entrance. Look around on the inside, though, and things start to seem off.

“This house has never been completed,” said Jerry Hicks, standing in front of a house where the lawn’s overgrown and plywood covers the windows. Hicks lives down the street. He said there used to be a house like this one right across the street from his home.

“The city actually came in and said, ‘This has got to come down. Because it was open, and it had been raining,’” Hicks said. “So they tore that one down. This one, I’m surprised they haven’t torn this one down.”

Hicks said he’s underwater on his mortgage, stuck in this unfinished subdivision. The gates at the entrance don’t work. People have sewer problems. Half the roads in the development have no houses, and trees and weeds have taken over, like some kind of post-apocalyptic movie.

Over the years, people squatted in some of the unfinished houses, said Hicks, and the wiring and appliances got stripped out of others. Vacancies are less of an issue now. Hicks said out of the 70-or-so homes in the subdivision, about six are vacant.

The most visible hangover from the recession is the state of the roads, which are rough and gravelly. Manhole covers stick up inches above the surface. At some point, someone put asphalt around them, to soften the edges. So they’re like small, square speed bumps. They roads have never been fully paved.

“And so now it’s starting to crack, and it just doesn’t look like it’s in a developed area, basically,” he said. “Have all these nice big houses, but the road is ancient looking.”

The I-20 Divide

The subdivision is a legacy of the housing boom before the bust.

Hicks bought his house in 2006, before it was completed. The next year, he moved in, just in time for the mortgage crisis and great recession. He and many of his neighbors stuck it out, but the developer didn’t. Hicks said the company bailed before it finished building.

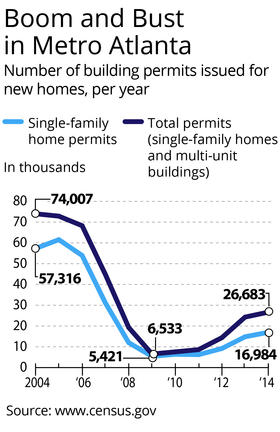

“We, along with Phoenix and a couple other cities, led the country in single-family subdivision development and sprawl,” said Dan Immergluck, a city planning professor at Georgia Tech. He said once the housing market collapsed there were no more buyers, but there were still all those subdivisions that were being built.

Immergluck said when the housing market collapsed, Atlanta was one of the hardest-hit metro areas in the country. But now, he points out, a lot of areas of Atlanta have recovered.

“Atlanta’s a paradox because as a metro, the indicators are pretty positive,” he said. “Job growth has returned, housing demand has returned.”

In places like Midtown and Buckhead, housing prices are rising. But Immergluck said Atlanta is a “dual market,” split by I-20. In Jerry Hicks’ ZIP code, 47 percent of homeowners are underwater, where the balance left on the mortgage loan is higher than the fair market value of the property.

“I think we have a bigger, kind of, race and space divide than lots of other cities,” said Immergluck.

Villages at Oakshire is in Atlanta City Councilwoman Joyce Sheperd’s district. She said for developers, the wealthier areas north of her district are low-hanging fruit.

“Then when you come to the southside of Atlanta, it is a whole different world in terms of trying to get developers to come in, working to make something happen,” Sheperd said.

She said there are four or five other subdivisions in her district that were never finished. Some are just what she calls “pipe farms.”

“They are now sitting there overgrown with pipes coming up out the ground, and nothing happening with them.”

She said she’s tried to get developers interested in the area. And she’s been to the Villages at Oakshire to take stock of the situation.

Hicks said city officials have been involved intermittently, but when he sees the development happening in other parts of town, he said he feels like a stepchild.

“Why do you put so much effort in that area, and completely ignore us altogether?” he asked. “So there’s animosity. You know, we’re angry about it.”

He said he’s stuck around for so long, partially to get his money back, but the main reason is his home.

“I fell in love with the house,” he said. “And I do think it’s going to turn around, just when.”

Hicks said a couple of developers have started poking around in the empty half of the neighborhood, and may finally build some houses there.

And one potential bright spot on his street is the paving. Atlanta voters recently passed a referendum to fund repairs all over the city. Councilwoman Sheperd put the streets here on the list of things to fix and said that should happen next year.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))