Atlanta’s Traffic Woes Trace Back To Railroads, Land Lotteries

For some people, the first image that comes to mind when you think of Atlanta is gridlock.

To deal with the slow-moving traffic, you can even find how-to videos on YouTube:

But why is the traffic so bad here? How did our founders design Atlanta that makes it different from other major cities?

Tom Weyandt, Mayor Kasim Reed’s former transportation adviser for the city of Atlanta, said there’s no natural reason for Atlanta to exist.

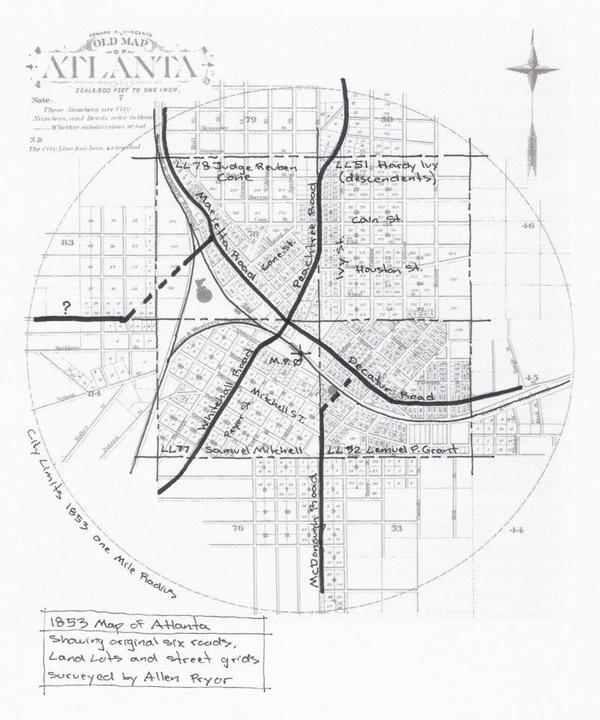

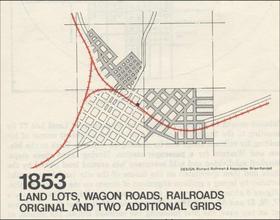

“There’s no mountain chain; there’s no desert; there’s no water – we’re here because of the railroads. The railroads came together right in downtown. The zero mile post is in Underground Atlanta,” Weyandt said. “And the city grew out along the railroads. That’s why we have these eccentric five-point intersections in many different places in the downtown area.”

The best example of a crazy intersection is obviously in Five Points — where Decatur Street, Edgewood Avenue, Marietta Street and two parts of Peachtree Street intersect.

But before we get to our bizarre streets – we need to go back in time first.

Expelling Native Americans

So in Georgia, there were two major Native American tribes: the Creek and Cherokee Indians. When white settlers arrived, Native Americans were forcibly removed from their homes.

In what’s now present-day Atlanta, a formal treaty was signed in 1821 between the Creek Indians and Georgia General Assembly. The Creeks got $200,000 out of that deal.

Farris Cadle, the author of ”Georgia Land Surveying History and Law,” said there’s evidence of bribery and conspiracy behind the signing of that treaty.

“We stole the land from the Indians and bushwhacked ’em and beat ’em up and basically took the land from them by military force,” Cadle said. “They were coerced into signing the treaties.”

Georgia’s Land Lotteries

This land was then distributed to white settlers through Georgia’s Land Lottery System in 1821.

For just 25 cents, white men, women and even orphans could put their name in a rotating barrel to claim some land. There were eight of these in our history and Georgia was the only state to distribute land this way on a large scale.

We can thank these early landowners for the lack of a logical grid pattern in Atlanta.

“The landowners were trying to maximize their profits from the sale of the lots that they were laying out. They put a minimum amount of land in the streets, so the streets wound up with odd configurations and narrow widths,” Cadle said. “And of course then, the rest is history. Atlanta became a big city and it had an odd and inconvenient street pattern.”

Railroad Tracks

Cadle said that as the railroad tracks were laid down, the landowners tried to make streets perpendicular or parallel to the railroad tracks and since trains like to twist and turn … it’s messy.

“Most of the transportation system is a radial system. So for almost any trip that you choose to make, you have to go in and then you have to go back out,” Weyandt said. “There are few arterial roads, so that’s complicated the travel patterns as well.”

Urban Sprawl

In many ways, Atlanta is the poster child for urban sprawl.

Jane Hayse is director of the center for livable communities at the Atlanta Regional Commission.

“Atlanta, just like several other Southeastern cities, there’s no geographic limit to how we grow, in terms of mountains, rivers, oceans. So we’ve grown in all directions,” Hayse said. “So people are traveling farther distances to get into our major employment centers and that also leads to congestion.”

Hayse said having to share our major interstate highway, I-75, with the large number of tourists during vacation months doesn’t help either.

Kim McCarthy has been reporting on traffic in Atlanta since 1997.

“When I first started flying with WSB, on I-85 we would never go north of 316. Now, we go up all the way to Gainesville,” McCarthy said. “We’ve all had to learn different, farther-out counties, farther-out roads, because the delays are stretching farther and farther.”

A Growing Region

“Traffic was bad, but it was nothing like it is now,” McCarthy said. “Hours of gridlock for people to get just to work.”

She says there are many reasons for this:

- As a transportation hub, we get slammed with truck traffic on I-75

- There are three major highways that intersect in the middle of downtown

- We have a weak public transit system

- Most of the metro area is not walkable

And Atlanta’s population is growing.

“Almost no one in Atlanta is native to Atlanta anymore, so you’ve got different driving styles from all over the country. People get confused,” McCarthy said. “They’re looking at their GPS and so many times you see people go across four lanes of traffic to get off at an exit because they’re not sure where they are.”

State Response

It’s hard for the Georgia Department of Transportation to keep up with all of the newcomers. Take the outdated intersection of I-285 and Georgia 400 that it’s just now getting to.

“From the conception of an idea to fix a road till the time that they actually are able to get all the studies done, all the funding and contractors in place, it could be 10 years,” McCarthy said. “And by then, that plan is obsolete, because there are so many people — more people — here.”

And there’s not much the state can do about the roads beyond building more express lanes and using better technology to manage the traffic. Meg Pirkle is chief engineer of GDOT.

“There’s not a whole lot of room to build. Commissioner Keith Golden has said many times that we can’t build our way out of this congestion,” Pirkle said. “And our board also has a policy that if we do build anything, it has to be managed, which means tolled or occupancy restrictions – that kind of thing.”

Public Transit

So the only way out of Atlanta’s traffic nightmare is serious investment in public transit.

Weyandt explained why we’re so, so far behind.

“There was an opportunity in the mid ’60s for five counties plus the city of Atlanta to join the – what become the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA),” Weyandt said. “Four counties plus the city opted to join that. Cobb County, in the mid ’60s decided not to even consider transit. And that coincided with a period of suburban white flight. I think racial issues were a significant part of decisions to not go forward with transit in many suburban areas.”

Take Gwinnett County. In 1990, 70 percent of voters rejected MARTA, when just about 12 percent of the county was made up of minorities. Today, it’s the opposite. Sixty-four percent of Gwinnett residents say they would welcome MARTA, according to a recent poll. Gwinnett’s now one of the most-diverse counties in the state, with more than half of the county made up of Asians, blacks and Latinos.

The Silver Lining

Traffic, and wasting days of your life sitting in it, is part of the deal when you choose to live in a region with a big city.

At least we can be grateful we don’t live in the nation’s capital.

A recent national study ranked the Atlanta area as 12th in the country for congestion. We spent 52 hours stuck in traffic and spent about $1,100 in wasted fuel and productivity. The Washington, D.C., area came in first, where residents spent about 80 hours in highway delays last year.

Jonathan Lewis, a transportation director for the city of Atlanta, said to improve traffic, the city is synchronizing traffic signals, converting one-way streets to two-way streets where possible and trying to connect neighborhoods to MARTA.

“There’s traffic congestion in the city. We just don’t have many opportunities to widen roads and our residents don’t necessarily want us to do that,” Lewis said. “Our opportunities are getting better use out of our existing right of way and create choices for folks.”

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))