Southerners do not have a monopoly on storytelling, but they’ve certainly made it an art form.

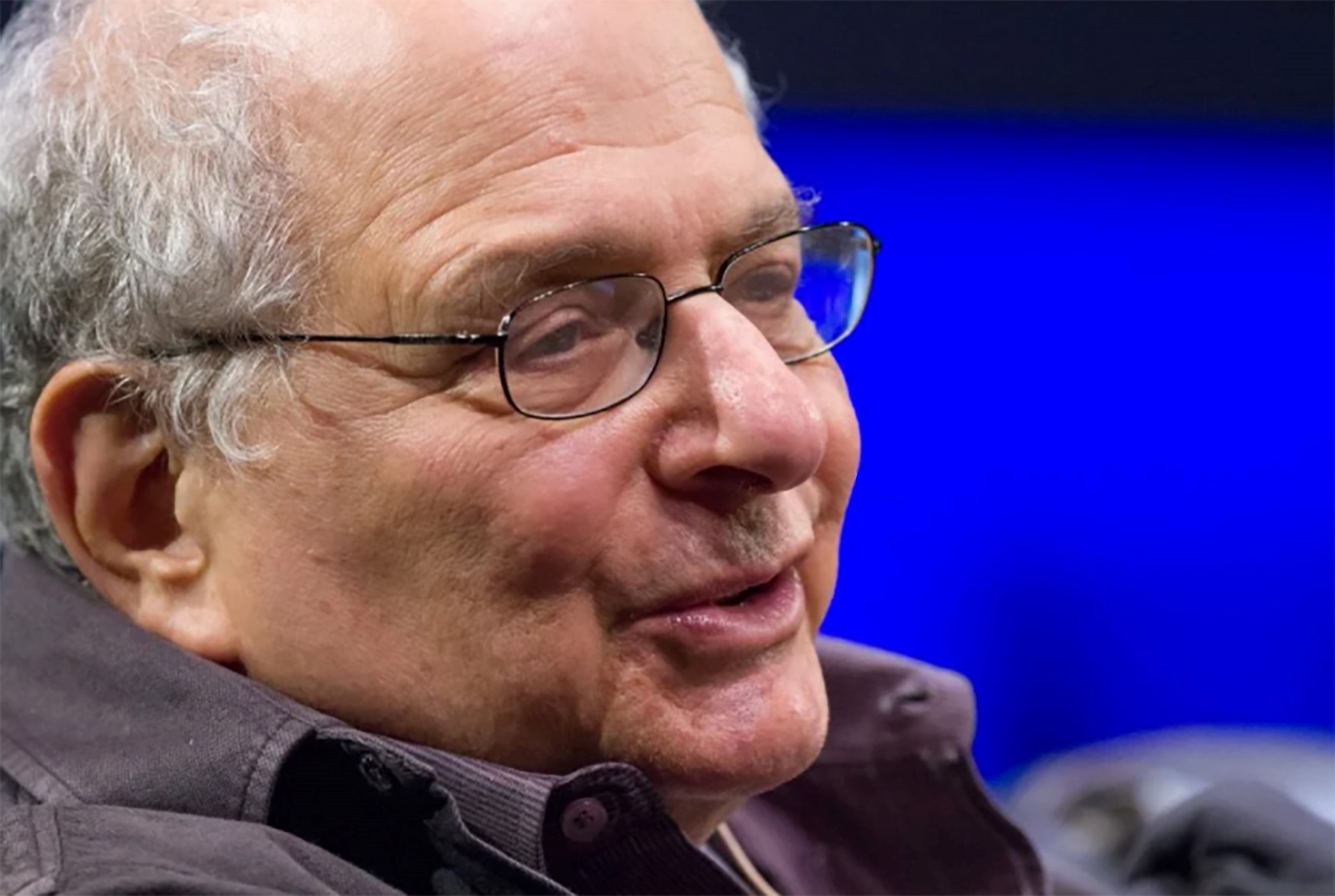

Alfred Uhry is an Atlanta native who is the first playwright to win the Tony Award, the Oscar, and the Pulitzer Prize. He will be giving a free, virtual lecture with The Breman Museum Sunday at 4 p.m.

“City Lights” host Lois Reitzes spoke with Uhry about some of the topics he will cover, such as race and religion.

Most of his works such as “Driving Miss Daisy,” “The Last Night of Ballyhoo,” and “Parade,” look at Jewish relationships in the South.

Interview Highlights:

On his Jewish upbringing in Atlanta:

“Race and religion [have] always been a part of what I write about because it was there in my bones from the time I was born.” He continues, “My generation of German Jews had Christmas trees, and Easter egg hunts, and no Jewish ceremonies. Although, a lot of us were confirmed when we were fifteen at The Temple. We had sort of nothing, it would have been easier to be Baptist or Episcopalian. I went to one satyr in my life and it was just a foreign country to me. It’s just too bad, it would’ve been nice. We grew up sort of gypped out of the good things about being Jewish.”

His thoughts on the significance of “Driving Miss Daisy:”

“I think the big mistake in the world is trying to turn the past into the present. You can’t do that. The past is the past and it happened the way it happened. I think both of them [Hoke and Daisy] made the world more possible, by beginning to realize that there could be warmth between the two, not just master and server. To have the story of ‘Driving Miss Daisy’ to take place in the year 2020 wouldn’t make any sense. This is a story of mid-century Atlanta, of a privileged, older Jewish woman and a Black driver. They were what they were.”

On The Temple being instrumental during the Civil Rights Movement:

“I think a lot of it was due to Rabbi Rothschild. He brought a political zeal to being Jewish, which was terrific. And we needed it. I don’t know if Atlanta Jews were particularly political before that, I just don’t think so.”