2 Scholars Discuss 1927 Film ‘The Jazz Singer’ As Part Of The Breman Museum Virtual Conversations

“The Jazz Singer: Blacks, Jews, and Jazz” film discussion will be held on April 29 at 7 p.m.

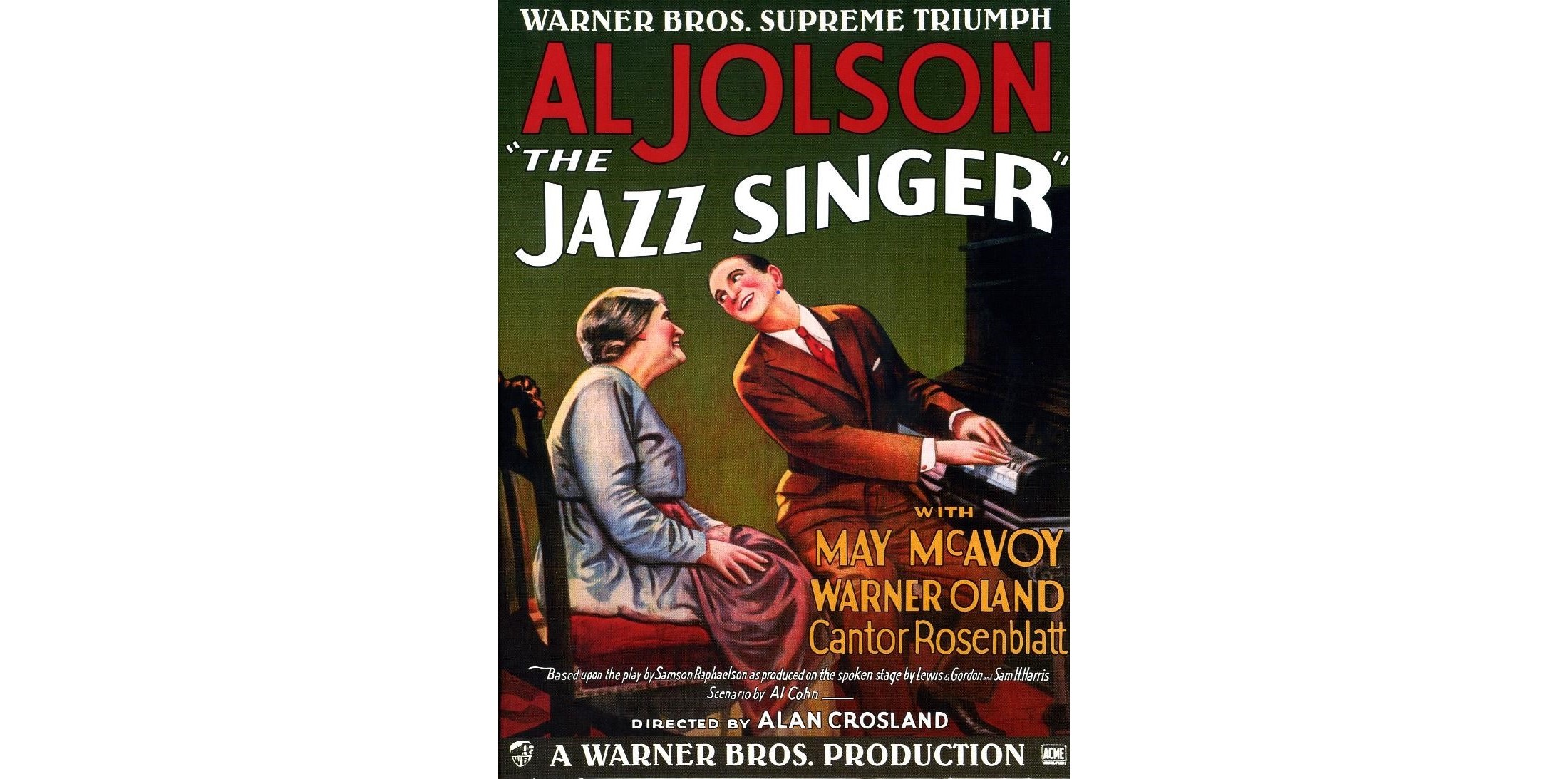

Courtesy of The Breman Museum

Legendary trumpeter Louis Armstrong wore a Star of David pendant around his neck all his life — the man embodying the link between jazz and Jews since the dawn of the art form.

African American and Jewish musical cultures were intimately connected in the first half of the 20th century. Both the richness and complexity of that relationship will be explored in a free online event from the Breman Museum on April 29.

Emory music professor the Rev. Dr. Dwight Andrews and Emory film professor Dr. Matthew Bernstein will discuss and show clips from “The Jazz Singer,” the film that began an era of synchronized sound to movies.

Bernstein and Andrews joined “City Lights” host Lois Reitzes via Zoom to delve into the linked histories of Jewish and Black communities in America, and the legacy of “The Jazz Singer.”

The 1927 film “The Jazz Singer,” starring the legendary and controversial vaudevillian actor and singer Al Jolson, is a challenging piece of cinema.

Though a stark example of our country’s worst impulses, with its racist representations of Black characters using white actors in blackface, it also invites a rich conversation about the links between early American Jewish and Black communities.

Musically innovative and culturally complex, the film still sparks important conversations about race and culture today.

“The Jazz Singer: Blacks, Jews, and Jazz” virtual film discussion can be streamed at 7 p.m. April 29 here.

Interview Highlights

On cinematic innovations:

“It was the first film that combined musical performance into the feature film narrative format,” said Bernstein. “Between the electricity of hearing [Al] Jolson sing and dance, and also some scenes where he ad-libs dialogue, people went crazy over this film.”

“It’s not great filmmaking — it’s fascinating, culturally. Because the film was a hit, and it cannot be just because of the excitement of sound,” said Bernstein. “For a Hollywood studio like Warner Brothers, which is created by Jewish immigrants, to decide that they’re going to make this film about Jewish life and the struggle of assimilation is really, really significant.”

Racism in early 20th century entertainment:

“Minstrelsy was one of the powerful ways to mythologize just how brutal slavery was, and minstrelsy made light of it,” said Andrews. “It creates a complete myth about slavery. And so it becomes not only a popular entertainment, but it furthers a popular point of view, which kept people from dealing with the brutalities of slavery.”

“Many were concerned that [early] film would be yet another way to further the kind of myth-making that minstrelsy did, but on a whole new level. So when you look at films like “Birth of a Nation,” and the kinds of myths that it created and really furthered the cause of many very racist and violent movements against Blacks, people began to take what they saw on the screen as truth,” said Andrews.

Interconnections in Jewish and Black American arts:

“We can see this wonderful synergy [in] the early popular American song as we know it … a wonderful weave of ethnic identities. Partially because of the intersection of these communities — Black and Jewish and others — but also because there are some inherent musical practices that are common to both cultures that go back to, perhaps, the beginning of time,” said Andrews. “Call and response, but also certain kinds of scales and modes that we associate with so-called ‘sorrow songs,’ the pentatonic scales that we associate with African American folk music.”