Georgia Receives Low Rank For Protection Of Records For Young Offenders

Say you were convicted of shoplifting a couple of times when you were 13. Fifty years later, you would hope that wouldn’t still be on your record.

But in some states, like Georgia, it probably is. And anyone can access it.

“Everyone assumes that these records are confidential and I think that’s because the public also wants them to be confidential,” says Lourdes Rosado with the Juvenile Law Center.

Rosado says most states – including Georgia – are doing a poor job.

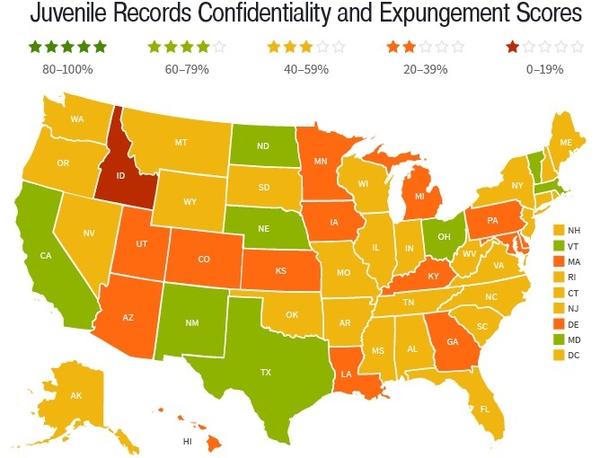

Georgia received just two out of five stars on a national report ranking states for how well they protect criminal and court records for those under 17.

Randee Waldman is director of the Juvenile Defender Clinic at Emory’s Law School. She hasn’t read the full report, but she says it’s pretty obvious to her.

“Georgia could do better in protecting our kids,” Waldman says.

In Georgia, you can’t get your criminal record expunged. You can only make a request to have it sealed.

There are a few situations where the crimes you committed when you were young automatically become public record. For example, if you commit a serious crime, like robbery or arson. But most of the time, it’s the minor stuff – like shoplifting. Do it twice, and your information is now public.

“Or a kid is adjudicated delinquent on shoplifting and then gets into fight while at their group home and is charged with simple battery,” Waldman says.

A public juvenile record makes it harder to access housing, education and employment. One of Waldman’s clients in Dekalb County is facing eviction after the landlord found out about her child’s record.

“I have a case right now where the parent has been told that she has 10 days to leave the house or the child must move out of the house within those ten days,” Waldman says.

Dina Sarver is from South Florida. She says her juvenile record almost prevented her from graduating from college. She served a six-month sentence for stealing cars when she was 15.

“Anyone with my first and last name and $18 can pay online and see my juvenile offenses,” Sarver says.

Lourdes Rosado says that’s counterproductive.

“It really prevents too many young people from growing up,” Rosado says. “They’re ready to pursue their education, to get jobs, to join the military. And it really flies against the whole purpose of the juvenile court.”

Sarver says she’s grateful for the juvenile justice system. It helped her get her life on track. But when she’s prevented from chaperoning her son on school field trips, it hurts.

“I’m sure there are many individuals out there who may have resorted back to a life of crime because they’ve seen that these restrictions aren’t something that they can overcome,” Sarver says.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))