How Georgia Is Trying To Expand Computer Science Classes To Help Fill Jobs

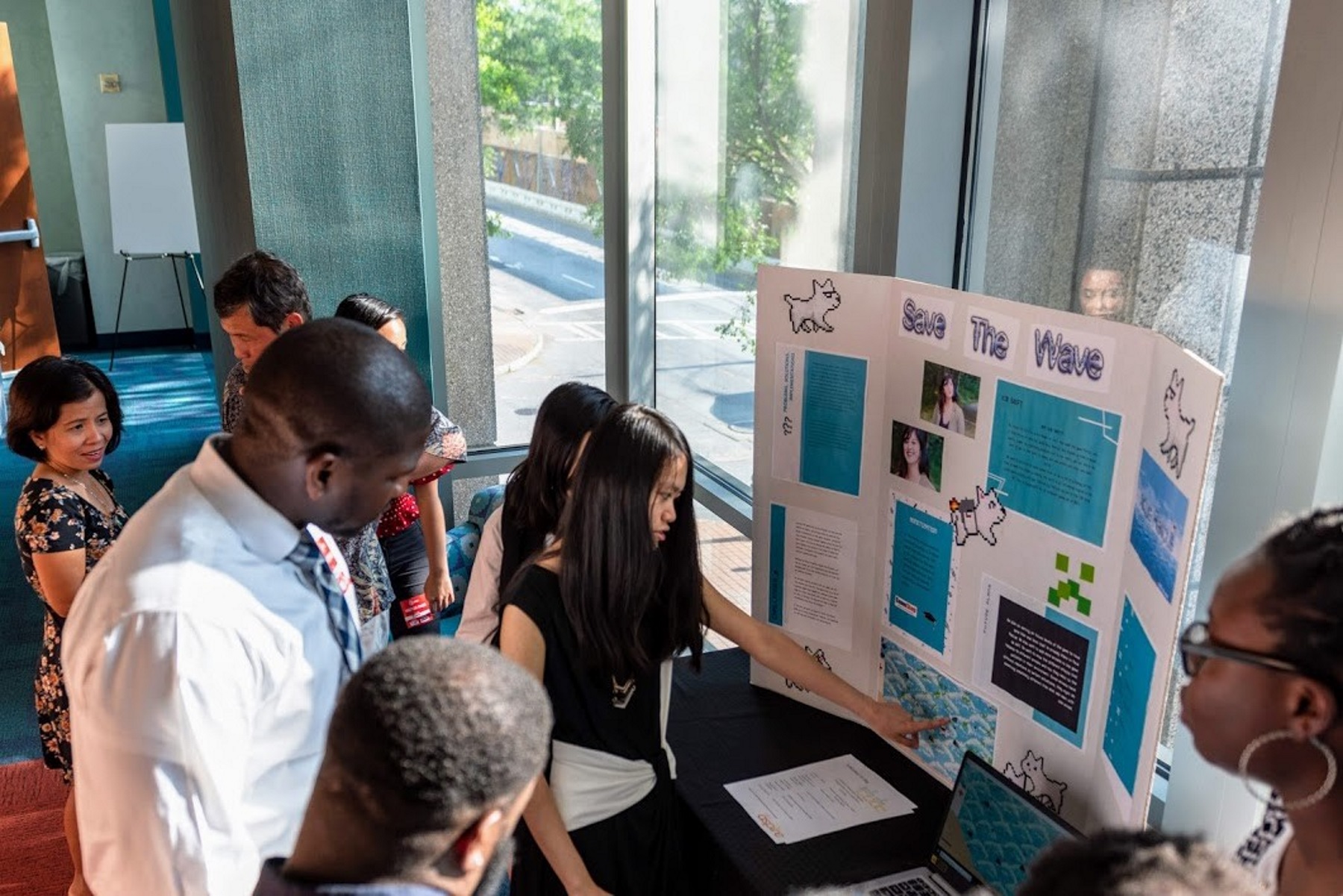

Jovita Chang explains her group’s final project, “Save the Wave,” a video game that teaches users about pollution and climate change. Participants took part in a seven-week Girls Who Code program at AT&T and presented their final projects on graduation night. This is the kind of innovation Georgia is looking for, but it could be tough for these students to keep the momentum going when they return to school.

Chris Montgomery

As Georgia becomes more of a technology hub, it’s facing some big problems.

For one, the state isn’t producing nearly enough computer science graduates to fill available tech jobs. According to the Georgia Department of Education, there are close to 20,000 open computing jobs in the state, but just 1,200 students graduate from Georgia colleges each year with computer science degrees.

Historically, Georgia’s K-12 public schools have offered computer science as an elective. Some schools offer Advanced Placement computer science courses. The state has nine different technology pathways students can choose, but they’re not available in every school or even every district.

In an attempt to expand computer science courses, state lawmakers passed legislation this year requiring middle and high schools to offer at least one computer science course by the 2024-25 school year.

The problem with expanding classes, though, is that there aren’t enough certified teachers to lead them. According to the Georgia Professional Standards Commission, which certifies teachers, as of March 2019, there were just over 260 teachers certified to teach computer science employed in Georgia’s public schools.

That’s an improvement from three years ago when the Georgia DOE says there were just 33, but the state will need more to meet the law’s requirements and schools’ needs.

Filling In The Gap

To some extent, nonprofit organizations have stepped in to help. Groups like Black Girls Code and Girls Who Code offer coding programs for young women and girls of color.

At a graduation ceremony for a Girls Who Code chapter at AT&T in downtown Atlanta, students present projects they’ve been working on during their seven-week summer program.

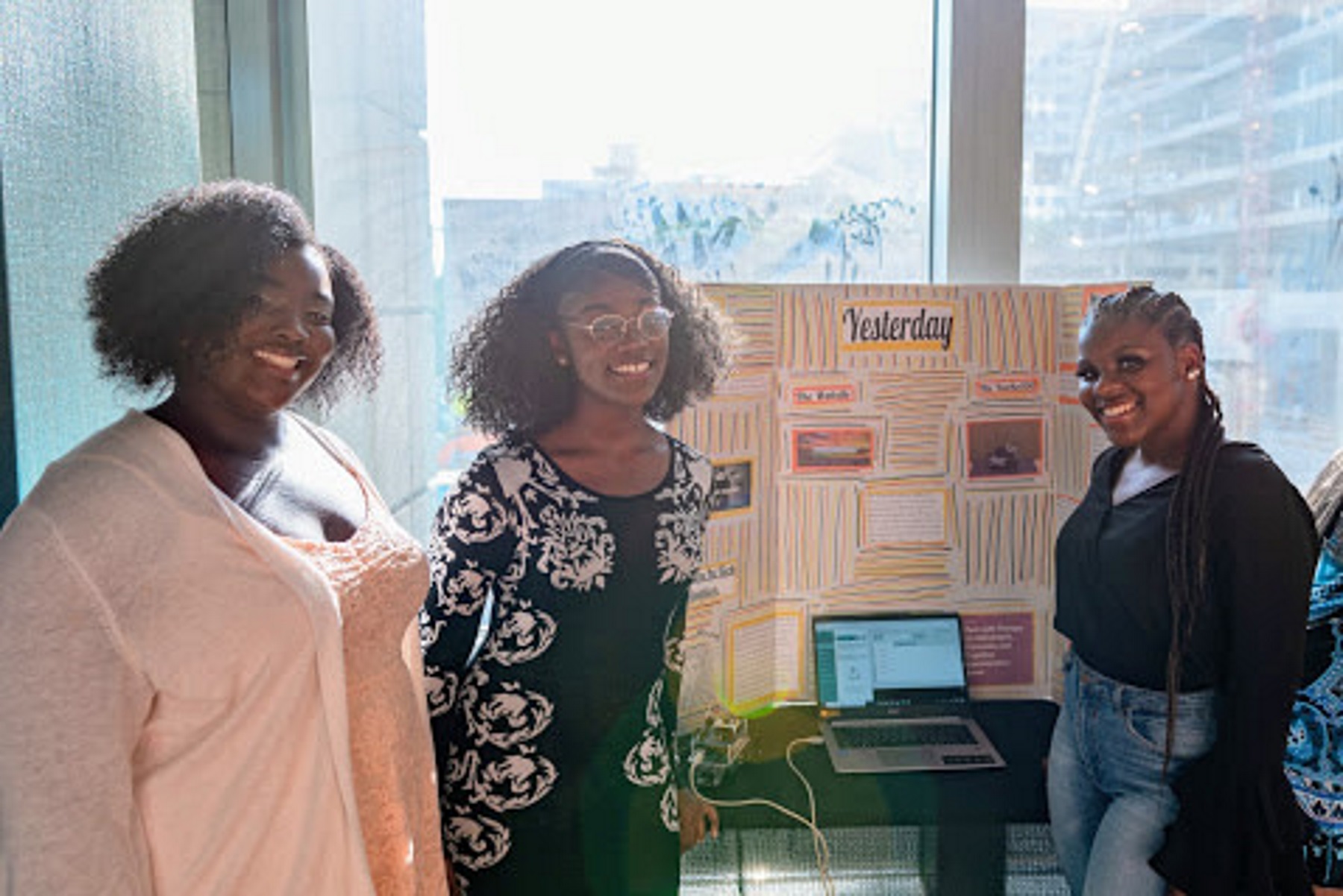

One group has developed a robot and a website to help dementia patients. They’ve programmed the robot to play “Hey Jude” by the Beatles because research shows music can trigger memories in dementia patients.

“We also programmed it to emit a red LED light, which is scientifically proven to help cognitive functions,” said Janiece James, who worked on the project.

Another group developed a game to teach users about pollution.

Three girls who called themselves the “Golden Touch Titans” developed a website to help women of color choose the right makeup shades for their skin tones.

This is the kind of innovation — and these are the kinds of students — Georgia is looking for.

But when they return to school in the fall, it could be tough for these girls to keep the momentum going.

The idea is that students that go to those coding clubs…will go back to their schools and demand that they have some experiences, some opportunities at their school.”

Bryan Cox, computer science program specialist at the Georgia Department of Education

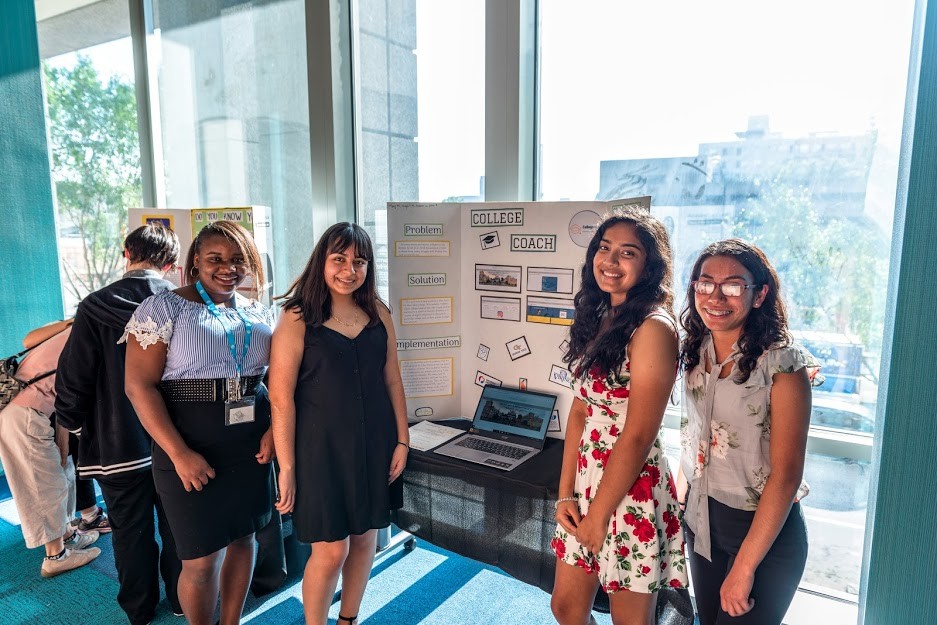

Sophia Huynh’s group built a website to educate people about their human rights. She says her school has one tech-related class.

“Computer science is only open to seniors,” she said. “So, it’s kind of limited.”

This is a common problem. Computer science classes are limited in a lot of schools. That’s one reason why lawmakers passed Senate Bill 108, the legislation that expands those classes.

But that leads to another problem: There aren’t enough qualified teachers to teach those courses.

A Teacher Drought?

State officials, like Bryan Cox, are well aware of this. Cox is the computer science program specialist at the Georgia Department of Education. The primary part of his strategy to recruit teachers is convincing existing ones to add computer science to their skill sets.

“[It involves] getting them to be cross-certified in computer science so that they could teach what are their core content areas as well as computer science, or, if they want, they can just become a computer science teacher,” Cox said.

Code.org, a nonprofit focused on expanding computer science in schools, has teamed up with the Center for Integrating Science, Math, and Computing (CISMC) at Georgia Tech to train existing teachers in computer science.

“We have trained over 3,000 [Georgia] elementary teachers and 200 middle and high school teachers,” said Sheela VanHoose, code.org’s director of state and government affairs.

Cox wants to recruit from various sources, including potential career-changers.

“… people from the tech industry that have either retired or decided they want to do something else more meaningful, more fulfilling, and they want to bring their talents to South Beach,” he said jokingly, referencing NBA star LeBron James’ announcement that he was leaving his hometown of Cleveland to play for Miami.

VanHoose says the “LeBrons” in the tech sector may not want to leave.

“The reality is these tech jobs are in demand. They’re well-paid jobs,” she said. “In many states, they’re one of the highest-paying jobs.”

VanHoose says it’s not unheard of to see someone leave the tech sector to teach, but it’s not very common.

To some degree, the state could depend on students like Sophia Huynh, whose group at Girls Who Code developed the website that teaches users about their human rights. Huynh enjoyed the summer program so much that she’s taking matters into her own hands when she returns to school.

“Next year, I’m making a coding club along with my other friend — he knows how to code,” she said. “‘So, I was like, ‘This is a perfect opportunity.’”

Bryan Cox says that’s exactly what the state hopes to see.

“The idea is that students that go to those coding clubs … will go back to their schools and demand that they have some experiences, some opportunities at their school,” Cox said. “So the schools will then offer them.”

VanHoose and Cox say the key to developing a teacher pipeline is expanding college programs for future teachers.

“I think the next hurdle for Georgia is to really start to link higher ed with K-12 and how they prepare future teachers,” VanHoose said.

Cox says colleges need to make computer science part of their teacher-training programs.

“Right now in Georgia, we only have one of those programs at Columbus State University,” Cox said. “But we aspire to have many, many more because that’s just the sustainable approach.”