To Keep Growing, Atlanta Has To Watch Its Water

On the Nov. 9 edition of “Closer Look,” Dr. Calinda Lee discussed the National Center for Civil and Human Rights’ work to educate others about the history of prison labor through a memorial at the Bellwood Quarry in Westside Park.

Brenna Beech / WABE

Two years ago, Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed spoke about the importance of water from the bottom of a giant quarry west of Midtown.

“Conservative estimates show that if we were to go just one day without water, the price tag to our local economy would exceed $100 million,” he said.

Reed and other local leaders gathered there because Bellwood Quarry is one way the city plans to ensure Atlanta doesn’t have to deal with that problem. The city is turning the old granite quarry into a 2.4 billion gallon reservoir to serve as a 30-day emergency backup water supply. The land around it will eventually be the city’s biggest park.

“When we are done with this project, it will change the city of Atlanta forever,” Reed said at the event.

So Atlanta is working on its future water supply, but there are other things that are out of the city’s control.

Small Supply

“We will always be a step away from the next drought,” said Katherine Zitsch, manager of natural resources at the Atlanta Regional Commission, while standing next to the Chattahoochee River.

“The Chattahoochee River, we’re looking at it right now. It is not the Nile. It is not the Hudson. It is not the Amazon. It is a small water supply. And we’re reliant upon that,” Zitsch said. “Atlanta started as a transportation hub, not a water hub. So we have to work with what we have.”

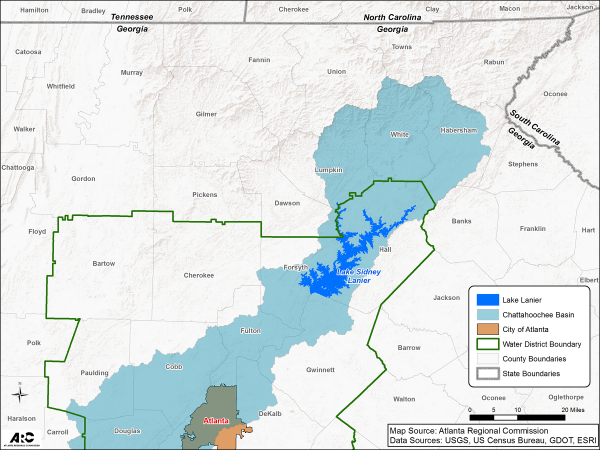

More than 70 percent of metro Atlanta’s water comes from the Chattahoochee. And the creeks and streams flowing into the river’s headwaters above Lake Lanier are small, she said, so the lake fills slowly.

“It doesn’t matter if it’s raining here,” she said. “It matters if it’s raining in those small creeks at the Lake Lanier watershed.”

Take Tropical Storm Irma. About five inches of rain fell in Atlanta when the tropical storm hit, but up above Lake Lanier only two inches fell, Zitsch said. So there can be a disconnect between what we experience in Atlanta, versus how our water supply is actually doing.

“Even if my lawn is wet,” Zitsch said, “great, I have a beautiful green lawn,” but areas around Lake Lanier might still be dry.

There have been a few big droughts in the past 15 years. One drought began last year. After a rainy summer, the state lifted water use restrictions in metro Atlanta, but Lake Lanier is still relatively low.

Water Wars

Another threat is Georgia’s neighbors. For more than 25 years, Florida, Alabama and Georgia have argued about the water that flows down the Chattahoochee and other rivers that start in Georgia.

“Litigation is a fact of life here in metro Atlanta,” Zitsch said. “We always have to be defending our water supply.”

There are six water supply-related lawsuits right now, including one in the U.S. Supreme Court. In that case, Florida is asking for a cap on Georgia’s water use. That could affect not only metro Atlanta residents and businesses, but also Georgia farmers.

An attorney appointed by the court has recommended siding with Georgia, and the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in the case.

Gil Rogers, director of the Alabama and Georgia offices of the Southern Environmental Law Center, said whatever happens with that one case, the fight over water won’t be resolved.

“We need to bring everybody to the table and come up with a bottom-up solution that will resonate with leadership of all the states,” he said. “We’ve had great conversations, but it’s not percolating up.”

Rogers said the challenges go back to Atlanta being a big – and growing – region, with a relatively small water supply.

“It’s always been grow first and ask questions later, and we’ve just got to get out of this mindset,” he said.

Beyond drought and lawsuits there’s also climate change, and whether that means less water or more, it will be another thing Atlanta has to adapt to. And how Atlanta uses water affects people, businesses and the environment downstream too. Atlanta’s not just near the headwaters of the Chattahoochee; five other rivers flow out of metro Atlanta.

“I’m just concerned that we are going to be permanently out on this ledge because of where we’ve grown and how many people we’ve stuck into this very small watershed,” Rogers said. “We’ve got to keep recognizing that’s a problem and taking it seriously.”

Using Less, For Now

Metro Atlanta has gotten better about conserving water. Rogers said since the big droughts in the past decade or so, there’s been more awareness that the Chattahoochee River can’t provide an unlimited supply of water.

Per capita and overall water use in Atlanta have both gone down.

But the Atlanta Regional Commission projects that metro Atlanta will grow by 2.5 million people by 2040, and all those people will need water.

“For the economic growth of Atlanta to continue we are going to have to make sure we continually improve our conservation and efficiency practices,” Zitsch said. “We’re not going to get additional water here in Atlanta, so we have to make sure we use our resources wisely.”

Atlanta voters are preparing to elect a new mayor and replace nearly half the City Council. In this moment of transition, WABE is exploring “The Future of Atlanta.”