Kids Are Learning To Be ‘Kind,’ ‘Respectful’ In Ga. Schools’ Behavior Intervention Program

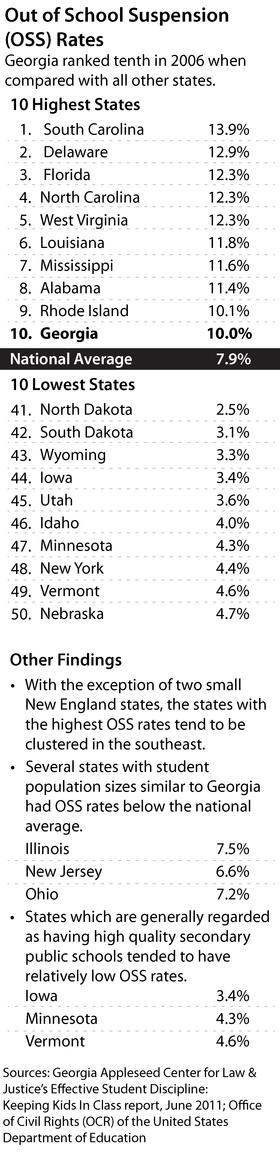

Georgia has one of the highest school suspension rates in the country.

But, it is dropping. To shrink the number further, some state officials are pushing a program that has helped reduce discipline problems nationwide.

Click the blue arrow to hear the broadcast version of this story.

Students at Peachtree Elementary School in Gwinnett County can socialize during lunch, but every few minutes what could be considered soft 80s rock pipes into the cafeteria.

Without any other cue, the kids stop talking and eat. It’s almost Pavlovian in nature, but it’s part of a program called Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports, or PBIS. It’s a program now in 400 Georgia schools.

It teaches discipline like any other school subject. Rules and expectations are taught over and over. It’s almost like learning math facts, says first grade teacher Sarah Hehir.

“First, I’ll teach them the rules, so they will be posted, we’ll read them together,” she says. “Then, we’ll model them in the classroom, and then the students will practice them.”

Her school focuses on two specific behaviors: being principled and respectful.

“To be respectful is to help somebody if they’re in trouble or to help them if they don’t understand something or to help them if they probably dropped something or forgot it,” third grader Ian Price says.

If you’d like to know what it means to principled, first grader Michael Kaplan can help you out.

“It’s to be kind,” he said.

When students behave in a way that’s respectful or principled whether in class, in the hallway or on the bus, they earn tickets. Those can add up toward prizes or trophies.

Peachtree Elementary adopted PBIS in 2010. Assistant principal Cheri Griffin says, at the time, she saw a lot of kids in her office with discipline problems.

“It would be 10-15 a week,” Griffin says. “And now you’re looking at our data, and we have probably 90-some discipline referrals for the year so far.”

In other words, they have about one-fourth of the problems they used to.

State officials notice numbers like that. Garry McGiboney, a deputy superintendent at the Georgia Department of Education, is a big proponent of PBIS. He says it comes down to a shift in focus.

“Where do you want to put your time?” McGiboney says. “Do you want to spend your time dealing with consequences, or do you want to put that same amount of time on the prevention side?”

McGiboney says schools that have adopted the program have decreased their suspension rates.

That’s no surprise to Randee Waldman, director of the Barton Juvenile Defender Clinic at Emory Law School.

“We’re looking at what was causing the breakdown in our school system,” she says. “Why were people acting out in a certain way and how can we get to them before that happens?”

Waldman is also an attorney who represents students in school discipline cases.

“Right now, we have a system that says, ‘You did x,’” she says. “We are immediately going to respond to ‘x’ in a punitive, reactionary way.”

That hasn’t worked well for Georgia, says Rob Rhodes. He’s with Georgia Appleseed, a nonprofit law center which has researched school discipline.

“It’s one of those situations where it’s not rocket science,” Rhodes says. “To the extent that a kid is not sitting in class in the seat, the chances of learning are substantially reduced, to say the least. And, of course, the data bear that out.”

Rhodes says schools that are tough and quickly suspend students are not helping the state’s lagging graduation rate.

For example, in 2013, 15 percent of Clayton County students were suspended. Just 56 percent of students graduated that year.

But even strong supporters of PBIS say it won’t completely eliminate discipline problems because kids will be kids.

“We’re not saying we’re not going to consequence poor behaviors, we are,” Bob Burgess, who oversees Gwinnett County’s PBIS program, says. “We’re going to address it, but we want to do it in a positive way. And then if the student continues to [misbehave], we want to provide those interventions and supports to help them self-monitor.”

Because of PBIS, Peachtree Elementary can focus on tough cases and learning environments have improved.

State officials are reluctant to mandate or require all schools to use the PBIS program, but hope schools will opt-in voluntarily.

Some Georgia senators are showing their support by debating a bill that suggests local schools adopt the program.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))