A Never-Ending Legacy: Gordon Parks’ Photography Permeates Atlanta

He died in 2006, but Renaissance man Gordon Parks is still making his mark on Atlanta.

In collaboration with each other and in conjunction with the Gordon Parks Foundation, two Atlanta galleries and the High Museum of Art have been featuring Parks’ photographs for the past few months.

Both the High and Jackson Fine Art have photographs from the collection “Segregation Story,” and Arnika Dawkins Gallery is displaying “American Champion” along with a smattering of iconic Parks photos.

These collections highlight Parks’ style and provide the backbone of his biography.

Born in 1912 in Fort Scott, Kansas, Parks grew up in poverty and segregation. He was the youngest of 15 children. When his mother died when he was 14, he had to find ways to support himself with odd jobs. One such job was playing piano in a brothel.

Parks picked up his first camera when he was 25 and got a job taking photos at the Farm Security Administration. The project was to document American life after the Great Depression, and Parks was assigned to Washington, D.C.

As an African-American in the social climate of the 1940s, he was barred from certain establishments. Despite this, he befriended Ella Watson, who was on the cleaning crew at the F.S.A.’s headquarters, and photographed “American Gothic, Washington, D.C.,” one of his most well-known photographs.

In 1948, Parks became the first African-American staff photographer at Life magazine.

There, he did series after series of photo essays. To document segregation in the South, Life sent Parks to Alabama in 1956. There, he encountered the Thorton family and ended up spending several weeks with three generations of the family in Mobile and in the country. The result was 26 photos in a spread called “Segregation Story.”

The photos at Jackson Fine Art and the High Museum, however, were discovered only recently. Since his death, the Gordon Parks Foundation has been surveying all of his photographs and stumbled upon 200 additional “Segregation Story” transparencies.

“Segregation Story” is a civil rights collection, a representative of part of Parks’ ethos to use his camera as a weapon against racism and poverty.

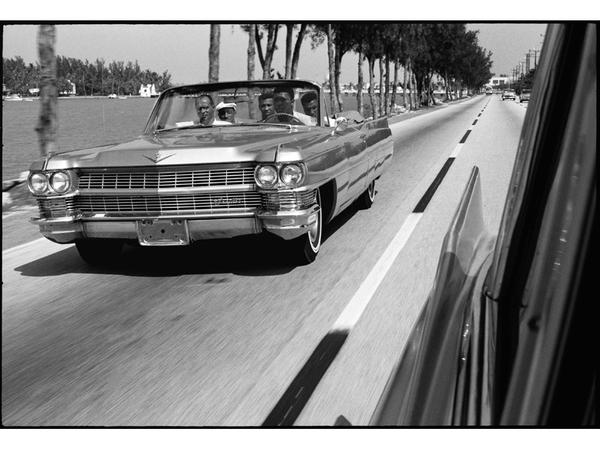

“American Champion,” on the other hand, shows his ability to connect with his celebrity subjects.

In 1966, he followed Muhammad Ali to Miami and London. At the time, Ali had a brutish, egoistic reputation, but Parks managed to capture a softer side of the famous boxer in the series.

Parks ended his career at Life in 1968.

He moved into Hollywood in the late 1960s and was the first African-American to direct a major Hollywood film. Two of his films, “The Learning Tree” and “Shaft,“ are included in the National Film Registry, which collects films that are “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant.”

In his lifetime, Parks took thousands of photographs, directed five Hollywood films, wrote several collections of poetry, and composed movie scores and classical pieces.

His work will continue to grace the walls of Atlanta’s galleries: “Segregation Story” at Jackson Fine Art until March 14; at the High Museum until June 21; and “American Champion” at Arnika Dawkins Gallery until March 27.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))