After Attacks On Election Integrity, Georgia Officials Work To Rebuild Confidence

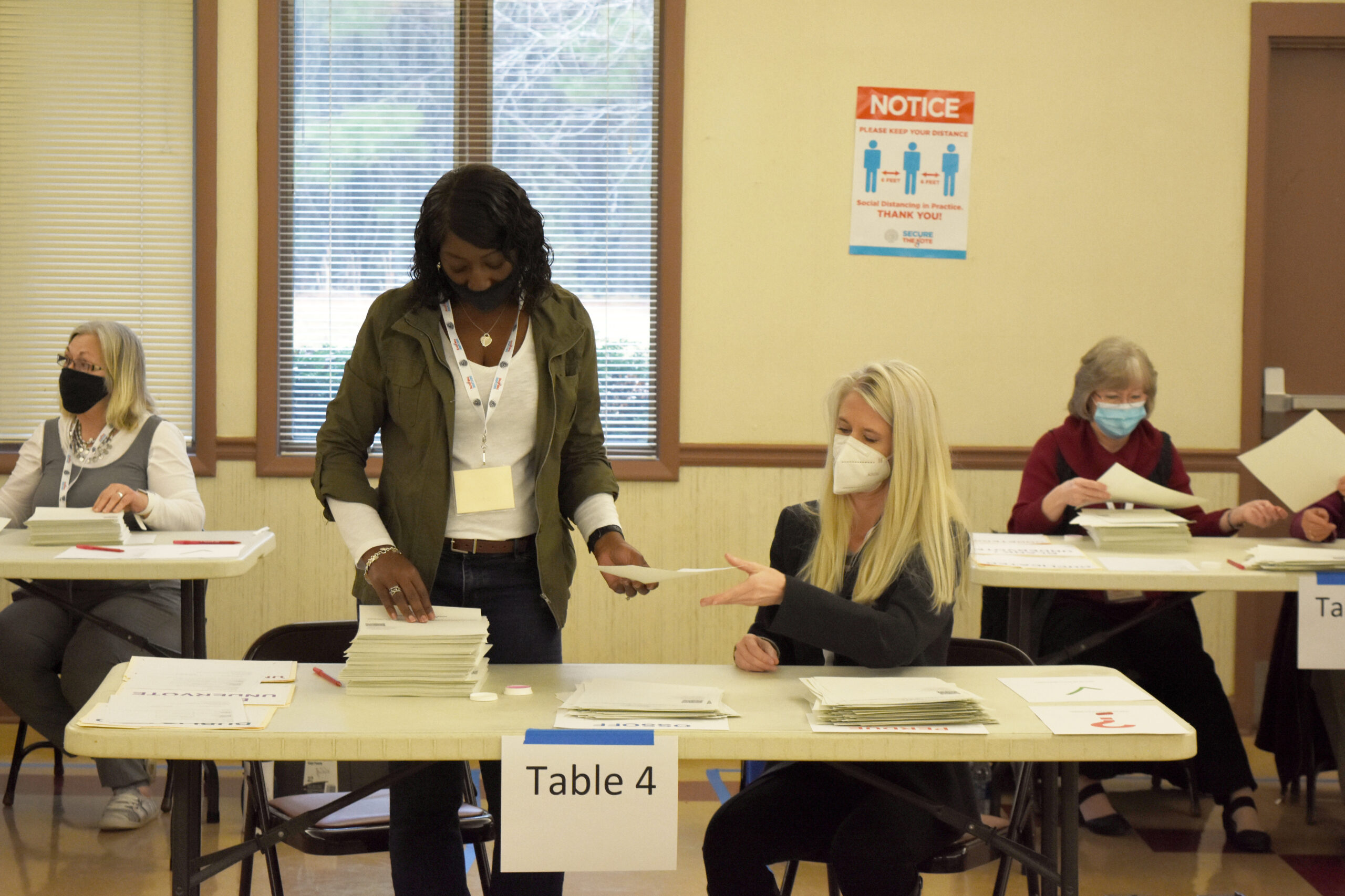

Bartow County, Ga. election workers conduct a full hand count of ballots in the Jan. 5 Senate runoff between former Sen. David Perdue and Sen.-elect Jon Ossoff as part of a voluntary recount aimed at improving voter confidence.

Stephen Fowler / Georgia Public Broadcasting

It’s been more than a week since the Georgia Senate runoff elections delivered control of Congress to Democrats.

But inside the Bartow County, Ga., Senior Center on Tuesday, a dozen teams worked in pairs to do a hand recount of more than 43,000 votes cast in the Jan. 5 runoffs.

The final margin for the races are outside the threshold for a recount, and the voters in this county an hour northwest of Atlanta are about 75% Republican — so the result isn’t close, or expected to change.

So why did poll workers spend a day conducting a voluntary audit at the end of an exhausting election cycle?

“A lot of my voters, a lot of my citizens, do not trust the voting system after November, after a lot of misinformation went out about this specific system,” elections director Joseph Kirk said.

Kirk is a firm believer in transparency and education when it comes to the state’s voting system – especially after one of the most secure elections in state history, one that saw record turnout and few reported problems.

But Georgia was also ground zero for misinformation and attacks on election integrity, led by President Trump and a number of top Republicans in Georgia and beyond.

Outgoing Sens. Kelly Loeffler and David Perdue made last-minute pushes to support a challenge to the Electoral College, the chair of the Georgia Republican Party and other lawmakers backed lawsuits seeking to overturn the state’s presidential results and the Republican-led legislature held hearings that promoted false claims of voter fraud and promised to crack down on voting rights.

The November election saw President Trump lose Georgia by about 12,000 votes and the 5 million ballots cast were counted three times, including a full hand audit required by law.

Kirk believes audits should happen after every election as a way to help the public trust their votes are counted and verify voting equipment functions correctly.

“I’ve spent a lot of time since the November election explaining to people on the phone that I know your vote was counted accurately, because we went back and checked that we did,” he said. Why would I want to stop saying that now?”

In this case, the audit examined the Senate election between former Republican Sen. David Perdue and Democratic Sen.-elect Jon Ossoff. Ballots were checked by pairs of election workers that audibly read off votes on the page, confirming with their partner before moving to the next one. From there, stacks of ballots are then counted in groups of 10 before each batch is entered into a tally sheet and eventually compared to the final totals.

State Election Board member Matt Mashburn stopped by the audit and was pleased with the process but frustrated with fellow Republicans who have spent weeks pushing conspiracies about the election and eroding faith and trust.

“The paradox is that we have these tools that we’ve never had before so that we can have a fair count and be confident with the tabulation and the results,” he said. “But the public has the least amount of confidence.”

In deep-red Bartow County, many Republicans expressed concerns with 24/7 absentee drop boxes, vote counting and the machines picked by the GOP legislature. In November, One voter even called the police to investigate a polling place for having a mysterious connection to China. It was just a power cord.

While fewer members of the public were there to watch the audit than November’s vote count, those who were there said it was still an important step in becoming an informed voter.

For Republican monitor Judy Kilgore, it helped seeing things with her own eyes, and knowing that some of her friends and neighbors she trusted were the ones doing the counting.

“I can personally hear them, I can walk around the tables, I can observe what they’re doing,” she said.

Kilgore said rhetoric around voting wasn’t helping turnout, especially for Republican candidates in an increasingly competitive state.

“You want to be able to get people to the polls to vote, you want them to have confidence in their vote, that it does count,” she said. “If you want your candidate to win… put a little bit more effort in it, but don’t sit back and be an armchair supervisor.”

In the aftermath of the 2020 election cycle, observing how the electoral sausage gets made isn’t just something for skeptical Republicans. Democratic monitor Karen Tindall threw herself into volunteering this year at the age of 71, in part because she wanted to help take partisan politics out of the way our votes are counted.

“I think we just need to talk about the process and explain it to people because the elections are safe and they are fair,” she said. “I think our elected officials have to think more about their oath of office to the Constitution and not their allegiance to their party… I mean, you have elected officials who are outright lying about how the elections went!”

After working for about eight hours, the final margin of error in Bartow County was less than a tenth of percent from the original results – expected, Kirk said, because humans are involved in the counting process that is normally done by machine.

The audit comes as Georgia’s legislature gets back to action, and some Republican lawmakers have promised to crack down on absentee ballots after spending weeks spreading misinformation and false claims of fraud.

There are signs that changes might not be so extreme: state Sens. Brandon Beach and Burt Jones were stripped of their committee chairmanships after backing lawsuits trying to overturn Georgia’s election results. A third senator, Matt Brass, was removed from the prestigious redistricting committee in favor of a lesser post.

And while some lawmakers floated the idea of removing no-excuse absentee voting enacted by (and primarily used by) Republicans for the last 15 years, Republican House Speaker David Ralston said he would appoint a new bipartisan committee to tackle any changes.

“Many Georgians are concerned about the integrity of the election system: some of those concerns may or may not be well founded, but there may be others that are,” he said Wednesday at a Georgia Chamber of Commerce event. “What we are trying to do is go through the perceived problems in a very thoughtful and responsible way.”

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))