At The Sweet Auburn Curb Market, History Is Also On The Menu

During a weekday dinner hour, a vast industrial warehouse at the intersection of Edgewood Avenue and Jesse Hill Jr. Drive is buzzing. Live jazz bounces off the walls, and the smell of pralines mixes with Panbury’s Double Crust Pies, wafting between closed retail spaces and merchant booths.

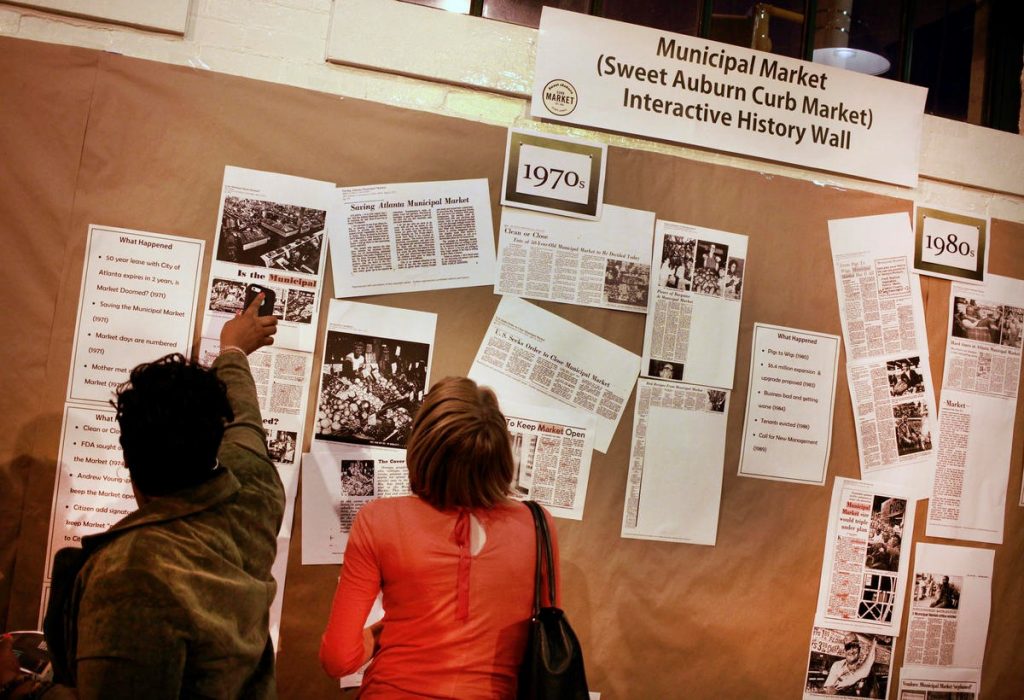

People are mingling at the Sweet Auburn Curb Market during Party with the Past, an Atlanta History Center event that introduces visitors to historic sites in the city.

Guests wander the aisles, sampling food from eateries, including Grindhouse Killer Burgers and Three Cities Pizza, which have stayed open after hours. Craft beer and wine are served to event goers amid conversations about the market — about its history, and what’s its always meant to the city

Born From Tragedy

The story of the Sweet Auburn Curb Market began in flames on the afternoon of May 21, 1917.

The Great Atlanta Fire, kindled by stacked mattresses, slowly raged through the Skinner Storage Company building on Decatur Street, then grew out of control. In consuming most of what is now the Old Fourth Ward, the fire killed one person, left nearly 5,000 homeless and burned an estimated 2,000 buildings to the ground. The New York Times reported that the destroyed structures included “the city’s finest homes and hundreds of Negro houses.”

A year after the fire, farmers began flocking to the city, gathering under tents on the scorched land of Edgewood Avenue to sell their goods. The makeshift outdoor market was an immediate success, giving city residents direct access to fresh meats and produce for the first time.

“Prior to the 1920s, there wasn’t really an inexpensive local market in Atlanta,” said Atlanta Food Walks founder Akila McConnell, a curb market customer and a guest speaker at the Party with the Past event.

“Everybody either had to shop at the more expensive Produce Row, or they were planting their own gardens,” she said. “There wasn’t this concept of local Georgia farmers coming into the city and selling their own produce.”

As the crowds grew, so did the need for the market to operate under something sturdier than tents. Nellie Peters Black, a women’s rights activist and agricultural reformer, and the Atlanta Women’s Club organized a drive that raised nearly $300,000 for the construction of a permanent fireproof brick building. On May 1, 1924, the Municipal Market of Atlanta opened its doors.

Blacks were permitted to shop inside the new market, but because of segregation they were sent outside to the curb to sell their goods. Despite being relegated to the curb, their booths drew big crowds, a success that lent the market its current name.

A Gathering Place

The Sweet Auburn Curb Market continued to thrive throughout the 1940s and 1950s, just as the surrounding neighborhood was blooming.

Jim Crow laws siphoned black residents into a small corridor between downtown and neighborhoods to the east. Residents like Alonzo Herndon, a former slave-turned-millionaire, began starting businesses, social organizations and churches in the area, mostly along Auburn Avenue. This activity led to an unprecedented boom in economic and social growth.

The Sweet Auburn district, which the Times described 20 years earlier as an “obscure Negro section,” had become a bustling epicenter of black business and social society in Atlanta.

By this time, the curb market had evolved into much more than a place to pick up produce and freshly butchered meats.

“A market is always first and foremost a gathering place,” McConnell said. “And that was part of the excitement, even back then. [The curb market] became this place where people of all socioeconomic levels could gather, and was more egalitarian than almost any other place in the city.”

“In Atlanta between the 1920s and the 1960s, a black person and a white person couldn’t even walk on the same side of the sidewalk,” she said. “But here, at the market, everybody shopped together. I’ve talked to folks who said there were only two places where black people and white people were treated equally at that time — in line at the ticket counter at the train station and at the municipal market.”

Decline and Recovery

As the 1960s ushered in the Civil Rights era, the golden age of the Sweet Auburn neighborhood was nearing an end. Black residents and business owners funneled out into newly available areas of the city, abandoning what Fortune magazine once dubbed the “the richest Negro street in the world.”

This exodus led to a steep decline of people and money coming into the district, a drop that would continue for decades. A lack of investment meant cracked sidewalks, shuttered businesses and buildings crumbling into disrepair. Blight and crime gave tourists few reasons to visit.

The National Register of Historic Places listed Sweet Auburn as one of the nation’s most endangered places in 2012, the district’s second such designation since 1992.

The curb market wasn’t spared the effects of the fall. Vendors were unable to pay rent. The building fell victim to vandalism and burglary. Construction made the market difficult for customers to reach. After being partially renovated for the 1996 Olympics, the market was badly damaged in the 2008 tornado that ripped through Atlanta.

However, the market endured. While surrounding shops were forced to shut their doors, the Sweet Auburn Curb Market held fast, bringing on Pam Joiner as manager in 2005.

By 2015, after several stops and starts, the market was full and bustling again, bringing in trendy new eateries while maintaining its community feel.

‘Everybody’s Market’

At the Party with the Past event, there’s little evidence of decline or neglect. The Sweet Auburn community is beginning to thrive again, and its neighborhood market stays packed nearly to capacity with vendors (and on any given weekday afternoon, a stampeding lunch crowd).

From segregation to today’s success, the market has been resilient, remaining a community bastion in providing affordable food. Vendors who’ve called the market home for more than 40 years now sell to the children and grandchildren of their former customers.

“Who wouldn’t want to go to a butcher who cut the meat of their mother, their grandmother, their great-grandmother?” said Dorthey Hurst, long-time customer and the market’s administrative assistant.

Indeed, it could be argued that it’s a tactile sense of legacy and history, of generations of love and kindness, that have held up the market, even through dark periods of history.

“It’s still a gathering place for all people without regard for socioeconomic level, without regard to race and religion and ethnic background,” McConnell said.

“I love Ponce City Market. I love Krog Street Market. But these are expensive places, and they exclude a lot of people. The Sweet Auburn Curb Market is egalitarian. It’s always been affordable. It’s always been focused on the community. It’s always been everybody’s market.”

Dionne Gant, owner of Miss D’s New Orleans Style Popcorn and Pralines, agrees.

She came to Atlanta and the Sweet Auburn Curb Market eight years ago, in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, to sell her popcorn, pralines and sweets. Since then, her candy shop has grown from a folding table at the entrance of the market to an addiction for many in the city and a restaurant partner of the new Mercedes-Benz Stadium.

Miss D’s is the perfect example of not only of what the Sweet Auburn Curb Market embodies — a gathering space, a community hub, a small business incubator — but also what it means to the community.

“It’s not about the bottom line,” Joiner said. “It’s about the people.”