Parents Hope Georgia’s New Dyslexia Law Will Make It Easier To Get Services

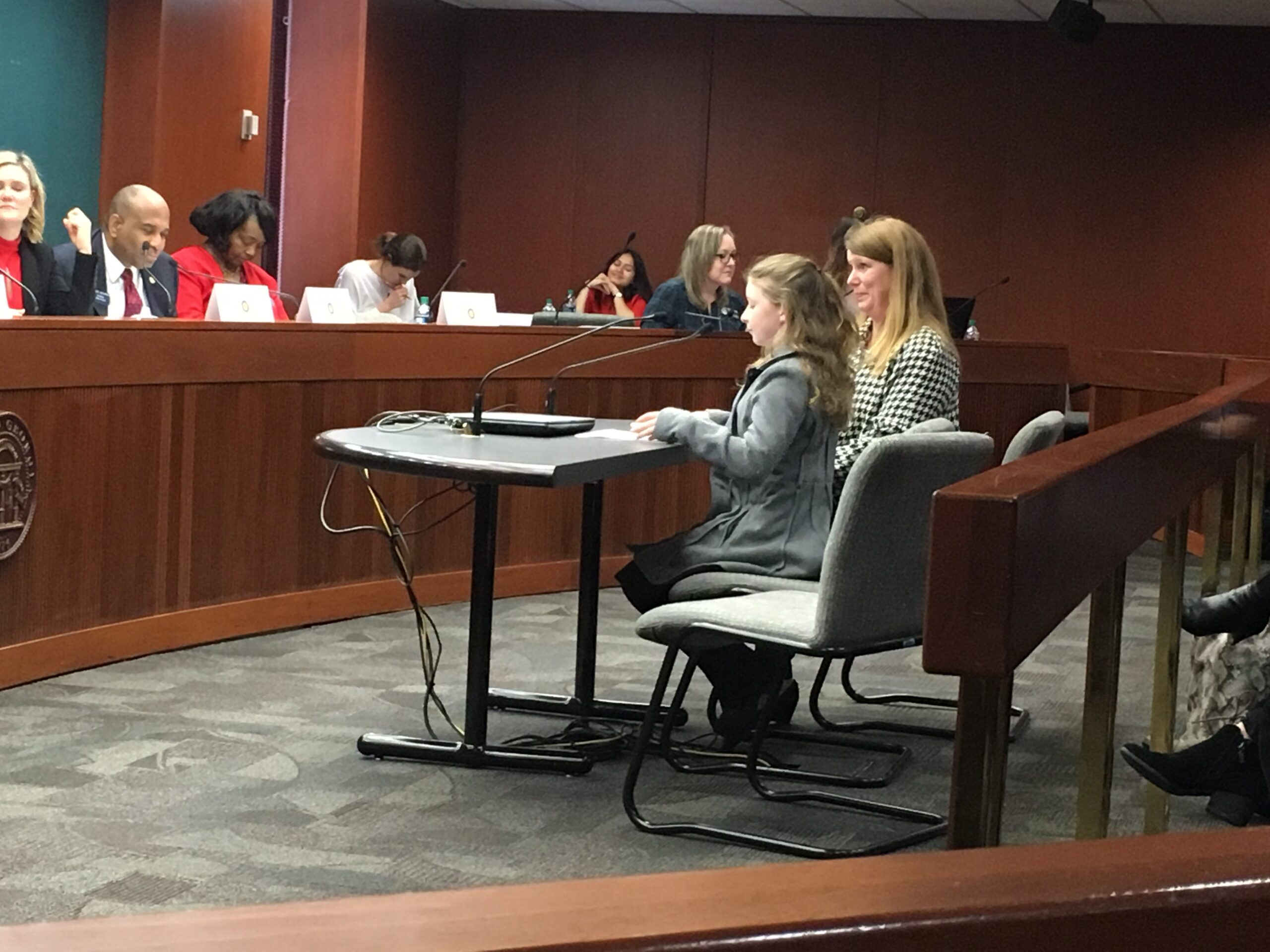

Audrey Jane Leftwich, left, testified about her struggles with dyslexia in front of a legislative panel in 2019.

Martha Dalton / WABE

In 2019, Georgia passed Senate Bill 48, a bill aimed at helping students with dyslexia. Experts say about 1 in 5 people have the learning disability, which often affects a person’s ability to read.

The legislation came together due to parent demand.

Even though federal law (called the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act or IDEA) entitles students with dyslexia to extra services, it doesn’t specify which ones. As a result, many parents say it can be difficult to get the therapies their children need.

Georgia’s law is more specific and names programs and services students with dyslexia should receive. Parents are hopeful the measure will make it easier for children with dyslexia to get more support in public schools.

Spotting The Signs

Lauren Taylor’s son is in fourth grade. When he was in kindergarten, she noticed he could say the alphabet as long as all of the letters were in order. But if she pointed to an isolated letter, like ‘e’ and asked him to name it, he froze. She urged his public school to evaluate him, and by the fall of his first-grade year, it did. He was diagnosed with dyslexia.

Theoretically, having a dyslexia diagnosis should have made it easier for Taylor to make a case for her son getting specialized instruction in school. He already had an Individualized Education Program (IEP), due to an earlier speech problem. Students with special needs are entitled to IEPs under IDEA.

Taylor’s son was supposed to receive specialized reading services for kids with dyslexia, among other services. However, she said the school didn’t always follow the IEP.

Peter Wright, an attorney who represents children with special needs, said this situation is common. Wright also has dyslexia. He’s successfully argued Supreme Court cases on behalf of students with dyslexia. Wright said when schools avoid giving kids specific dyslexia services, it’s often because they don’t have teachers who are trained in those methods.

“School districts are not going to say, ‘We don’t have any staff that are trained in the Susan Barton technique or the Orton Gillingham approach,’” he said. “They’re going to try to talk the parent into a different alternative.”

Susan Barton and Orton Gillingham are the names for evidence-based structured literacy programs used to teach students with dyslexia.

You’re expected, as a parent with a dyslexic student, to be an attorney, to have special knowledge about U.S. laws and regulations. You’re expected to be an educator with knowledge as to what your children are supposed to learn at every level.

Diane Weinberg, whose son has dyslexia

Wright conducts training for parents of dyslexic students across the country. He said parents who successfully get services for their kids with dyslexia often have to convince school officials of the severity of the problem.

“[They have to think], ‘How can I get them to see it the way the private evaluator saw it?’” Wright said. “That’s effective, powerful advocacy, and it’s not easy.”

Lauren Taylor has found that out the hard way. In the office of her Brookhaven home, she took out several enormous binders full of documents.

“This is [my son’s] first year of public school,” she said, plopping the first binder on the floor. “This is the second year, which is first grade rolling into second grade. Here’s his original eligibility for his IEP for dyslexia.”

Taylor’s massive notebooks contain all kinds of information, including psychiatric evaluations, notes from school meetings and test results.

“One of my folders … is dedicated to nothing but email correspondence,” Taylor said.

She said her son does get Orton-Gillingham tutoring in school now, and the school’s principal has been supportive. However, she said, there have been times when her son’s IEP hasn’t been followed. This past fall, for example, he wasn’t allowed extra time on a standardized test, which is outlined in his IEP.

Taylor wants to make sure other parents know their rights so they can advocate for their kids.

“That’s my fight,” she said. “School districts don’t tell people what to do. They don’t tell [parents] there’s no road map.”

Parents Turned Experts

Diane Weinberg’s son, Isaac, who has dyslexia, was in a different school district but in a similar situation to Taylor’s son. Weinberg testified in front of lawmakers last year, urging them to pass dyslexia legislation.

“[Isaac’s public] school has done everything within its power to provide him with the best education possible, but the school is just not equipped to meet his needs,” she said.

Similar to Taylor, Weinberg’s dining room table is full of books on dyslexia, packed binders and teaching tools. After a full day of work, she often helps Isaac with his homework.

“You’re expected, as a parent with a dyslexic student, to be an attorney, to have special knowledge about U.S. laws and regulations. You’re expected to be an educator with knowledge as to what your children are supposed to learn at every level,” Weinberg said.

Weinberg is an attorney. She doesn’t practice education law, but she said she’s had to learn it. Because it’s common for kids with dyslexia to have other disorders, Weinberg takes Isaac to five different kinds of therapy sessions every week.

“You’re also expected to make money or have somebody in your family making money,” Weinberg said. “So that, as well as having a job to have time and the flexibility to take your child to all of these appointments.”

Weinberg said her family is lucky. They can afford therapy appointments and private school for Isaac. She knows some families don’t have those resources.

“It becomes almost a problem that if you have enough money, then maybe you can get your child help, and if you don’t, well, then, good luck with you,” she told lawmakers last year.

Isaac has been in and out of public and private schools. This year, he’s at a private school that specializes in teaching kids with learning disabilities. He said it’s a good fit.

“I feel like I’m learning more, and they have better skills for my dyslexia,” he said.

Weinberg hopes this will last, but she said it’s hard to predict. She’d like to feel confident sending Isaac to local public schools, but she’s not sure it would be a good option for him.

‘It’s Still Hard To Talk About’

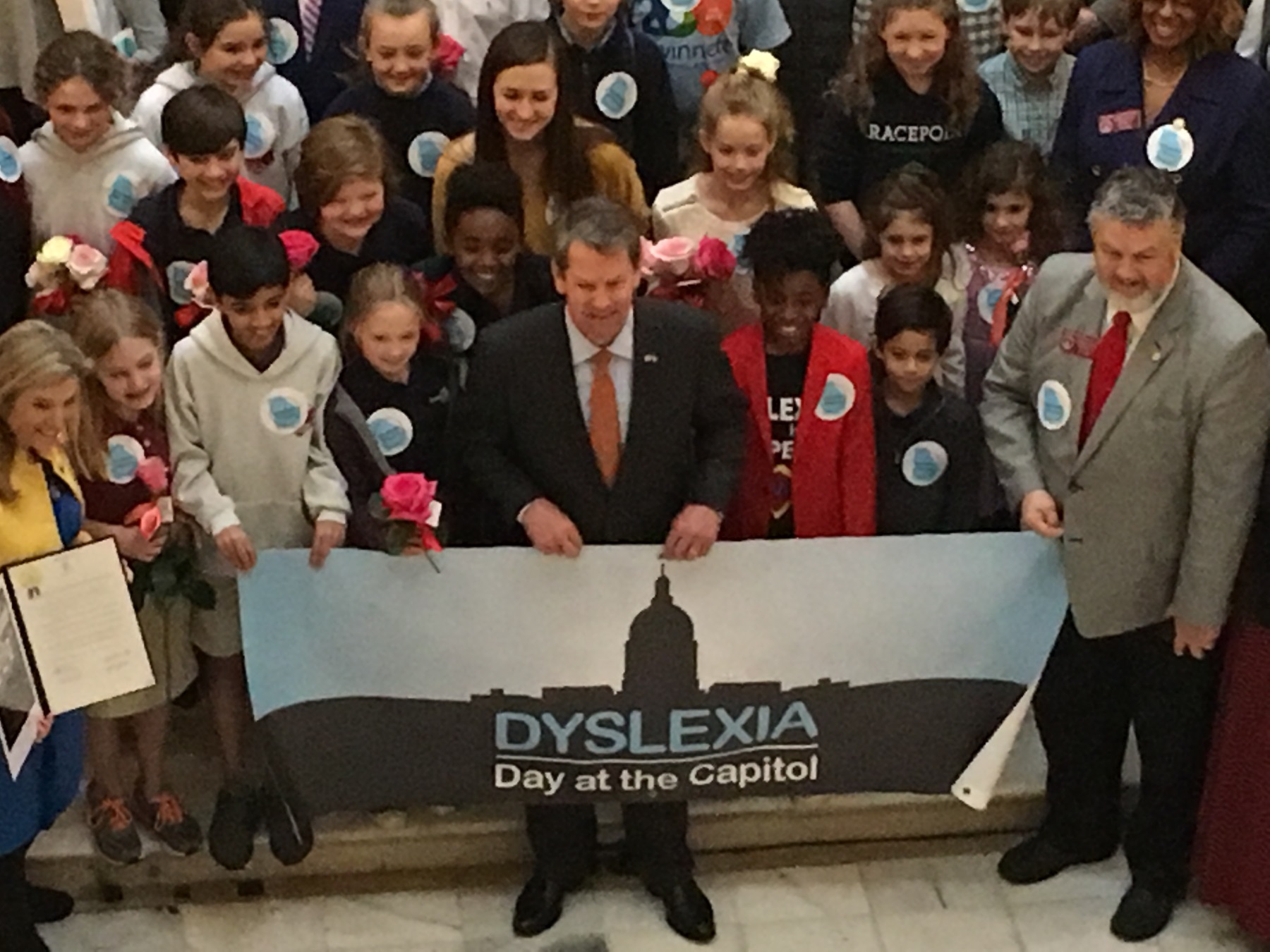

Georgia lawmakers listened to parents, including Weinberg, last year while the law was under consideration. Students also urged legislators to take action, describing how hard it was trying to keep up with their classmates.

“Before I was diagnosed, I would go to do my homework, and I would always start off in a good mood, but I would end up in tears,” said Brynn Haynes, who was in fourth grade at the time.

“Somebody [had] to read me my test [in elementary school],” said high school student Jenna Benedict. “My teacher decided that students would read me my test instead of her, and it made me feel like I was stupid and dumb, and it’s still hard to talk about today.”

“Our struggles as dyslexic children are similar but are very personal,” said Audrey Jane Leftwich, a fifth-grader at the time. “The opportunity for our teachers to have training so they can identify dyslexia in the classroom will stop them from guessing what is going on with struggling readers like me.”

That’s why Georgia lawmakers said they passed the legislation. They don’t want teachers to guess what’s going on with kids, and they want the entire process to be easier for parents and kids.

“Dyslexic students don’t seek pity,” said state Sen. P.K. Martin, R-Lawrenceville, while presenting the bill to the Georgia Senate last year. “They seek resources and techniques so they can better succeed in school. Their parents seek a partnership with their schools, as they search for ways to reach and assist their students who often struggle with homework and other assignments.”

The opportunity for our teachers to have training so they can identify dyslexia in the classroom will stop them from guessing what is going on with struggling readers like me.

Audrey Jane Leftwich, a fifth-grader at the time

Martin, who chairs the Senate’s Education and Youth Committee, also sponsored SB 48.

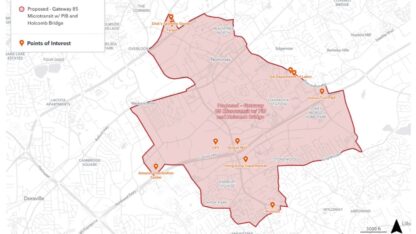

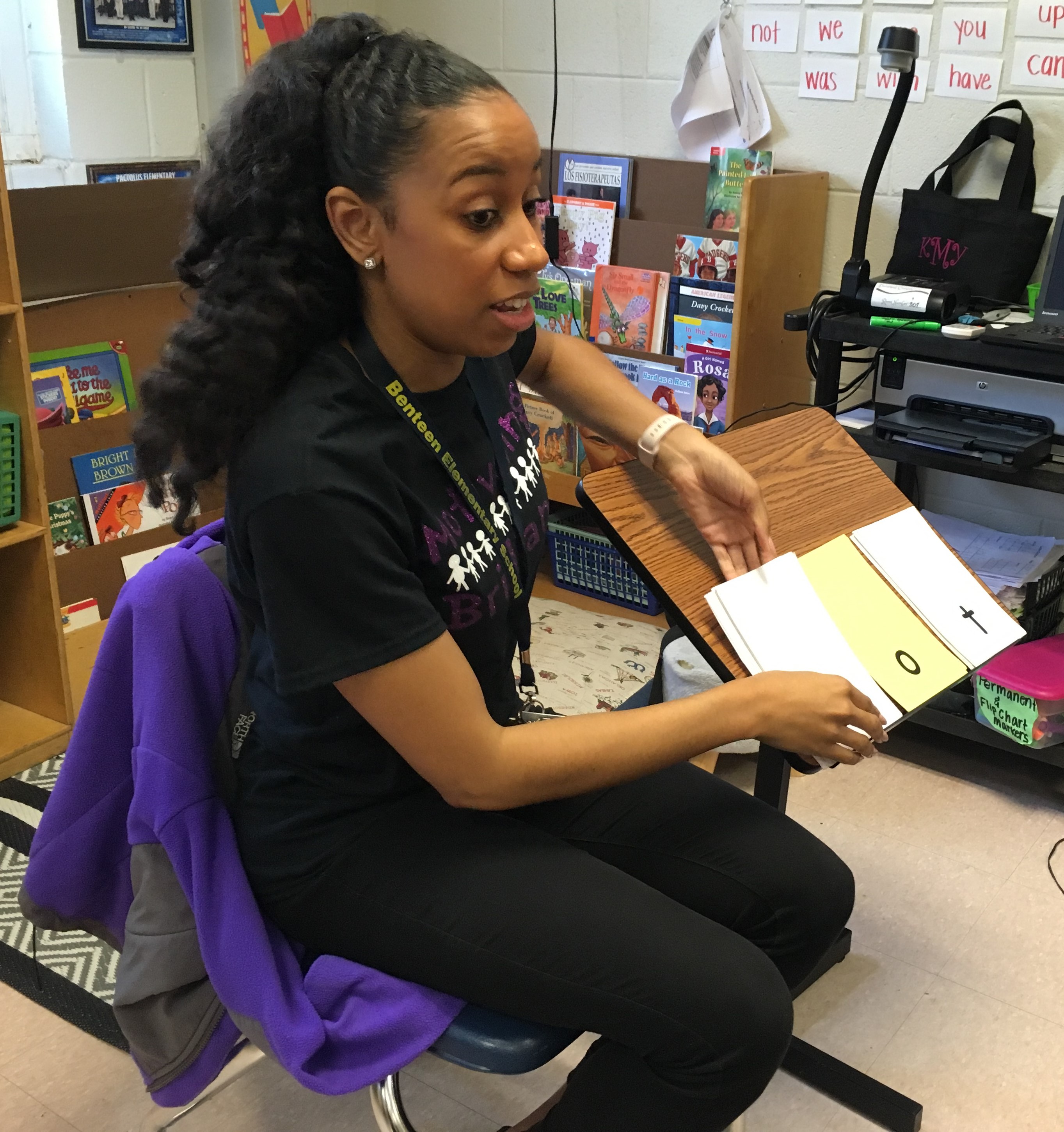

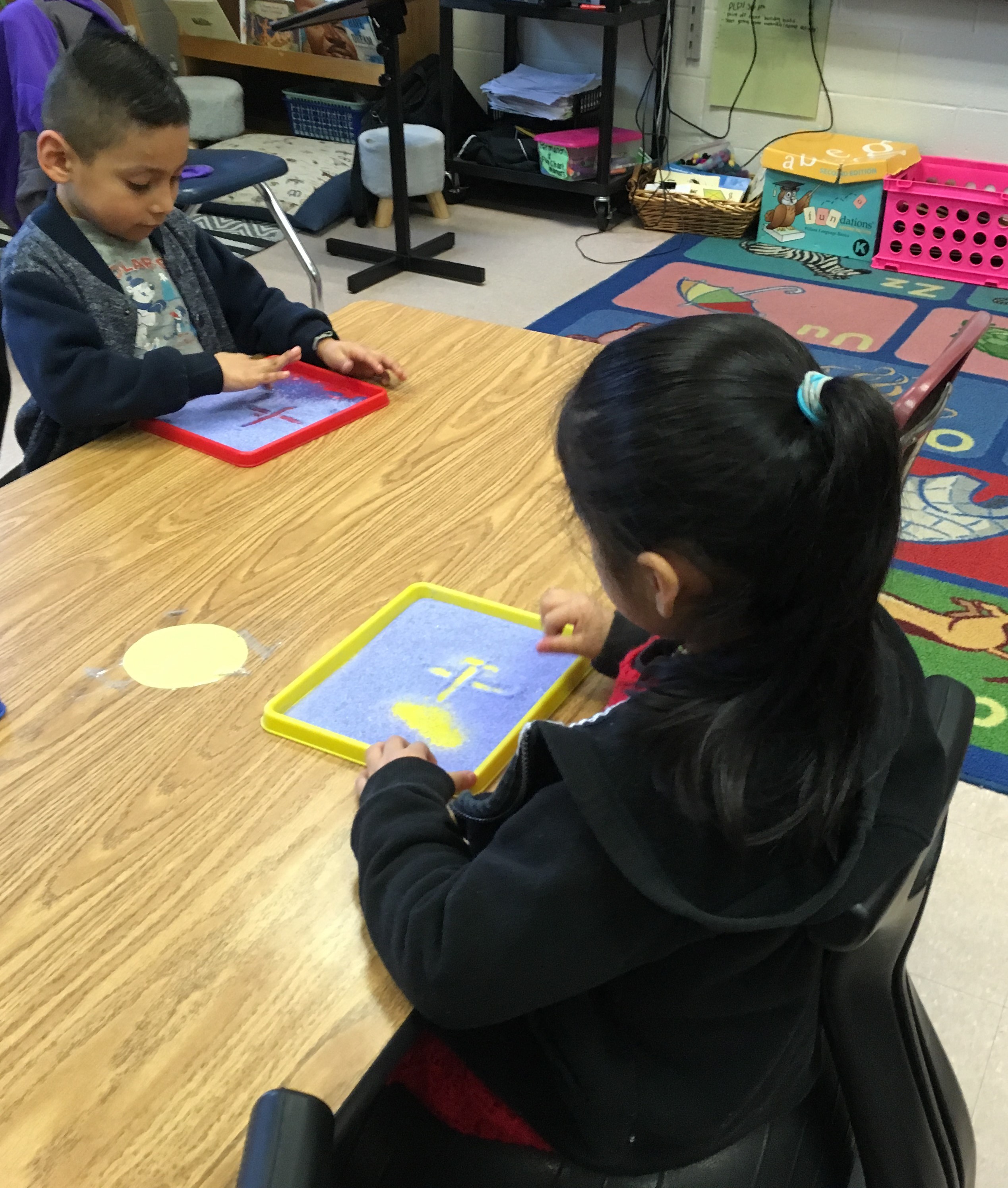

According to the law, the state will launch a three-year pilot program to address dyslexia in the fall of 2020. Six school districts will participate. Three of them are in metro Atlanta: The DeKalb County School District, Atlanta Public Schools and the Marietta City Schools. The program will focus on screening kindergarten students for traits of dyslexia and enrolling students who qualify in a reading program approved by the International Dyslexia Association (IDA).

The state will eventually require that teachers be trained in methods used to teach dyslexic students. The state has issued a handbook for teachers so they can more easily recognize the signs of the learning disability. The idea is to help schools specialize more so that families can spend time around the dinner table without rushing off to spend hours doing homework.

Read Part 2 of series here