What Spike Lee Winning His First Oscar Means To This VOX ATL Teen

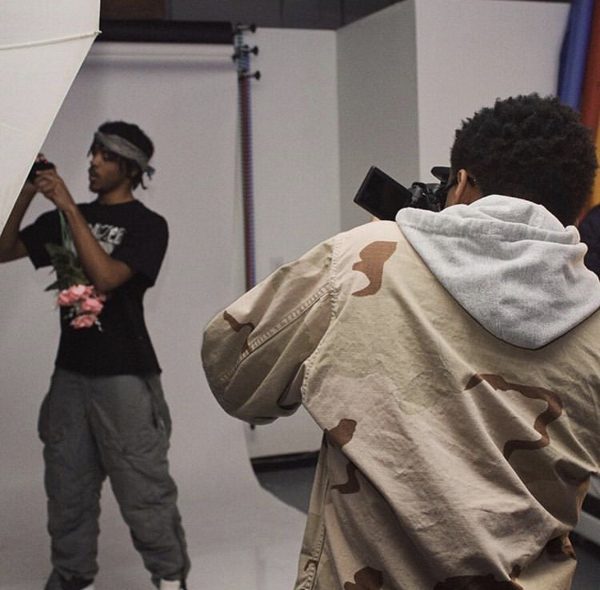

VOX ATL’s Malcolm “Mack” Walker, left, works as script supervisor at UCLA’s 2018 summer film institute. “As filmmakers, our No. 1 goal should be to do what we love for ourselves and our audiences,” said Walker, an aspiring screenwriter and director. He was happy about and inspired by Spike Lee’s Oscar win.

Courtesy of VOX ATL

By Malcolm “Mack” Walker

Last month, when Samuel L. Jackson and Brie Larson announced Spike Lee’s Academy Award win for best adapted screenplay for “BlacKKKlansman,” the first thing I did was get up and scream. It was late; my siblings were probably asleep, and my mom was already tired of my cheering and grumbling in response to the previously presented awards that night. This one was different though — she let me.

Spike Lee, for the first time in 30 years got what he deserved.

As a young aspiring screenwriter and director, I’ve challenged myself to consume as much film as I can in order to understand the career path that I so desperately want to be a part of.

In the beginning years of my journey, I became angered by the lack of African-American representation that I saw in films. Usually, it was some period piece about slavery in the 1800s. Those films may be “quality,” but if a slave story is the only film genre that Hollywood could think to put black people in, then we definitely have a bigger problem.

I wanted to find films that represented me in all forms, not just the stereotypical plays of blacks being “criminals” or “hoodrats.”

Why couldn’t we just be regular people? Why couldn’t I see films about what I experienced in real life? Why weren’t there any films that I could relate to that included black people playing key roles?

I didn’t get this answer for a while, until I got my first taste of Spike Lee.

Spike Lee’s joints are the amalgamation of everything that I wanted to see in film. They were hip, they went away from the classic storytelling that we’ve seen countless times, and, most importantly, they were black.

In a blatantly whitewashed industry, I was finally able to experience the life that I live on screen, and witness events that I see every day told through Spike Lee’s characters.

For example, Lee has always been outspoken on gentrification in predominantly African-American communities. His 1989 film “Do the Right Thing” is a testimonial about race relations as a result of the gentrification of his character’s Brooklyn neighborhood. Gentrification is a growing issue in Atlanta right now, due to rising prices in the city and white people moving into African-American neighborhoods, rebuilding everything and shooting prices up beyond what most people who originally live there can afford.

Instead of having his characters just deal with this injustice, Lee “fights the power” and gives them a voice — something many other films fail to do on numerous occasions.

Another aspect of Spike’s filmmaking that I love is how he portrays black love through his camera work, dialogue and use of shadows and editing. It’s become increasingly apparent to me that no one shoots a sex scene as masterfully as Spike Lee does.

“Mo’ Better Blues” proves to be the best example of this that I have ever seen. The main character, musical prodigy Bleek Gilliam (played by Denzel Washington), is in a difficult position with the two women he cares for, Clarke (Cynda Williams) and Indigo (Joie Lee). Spike shows this conundrum through a sex scene where Bleek accidentally calls one of the women by the other’s name.

The intimate scene is set up well through the use of close-up shots of the actors, silhouettes and red light to set the tone as lusty and passionate. After Bleek slips up, Lee uses match cuts between both females snapping on him angrily while using identical dialogue, further stressing Bleek’s (and the audience’s) confusion in separating the two women he wants from each other.

Everything about the scene was real to me. I could feel the love, lust, passion and anger from the actors involved, which is something I can’t say for a lot of films I have seen in the past.

A couple weeks before Spike’s Oscar win, I was doing research on African-American screenwriters and directors and found myself in disbelief by the fact that only four had won for awards surrounding screenplays, and that there has never been a black person to win an Oscar for best director.

All of this caused me to wonder if there would ever be another African-American to win before I was able to make a film that was close to Oscar-worthy. Spike Lee’s more than 30-year journey to getting his first Oscar answered that question for me: It doesn’t matter.

As filmmakers, our No. 1 goal should be to do what we love for ourselves and our audiences. Seeking the approval of award shows and making “Oscar-bait films” just ruins our art. We uplift, inspire and use our characters to speak truth to power.

Spike Lee, one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, did this for 30 years with minimal notice from the mainstream, and so can I.

So when the time comes where I’m standing on that glorious stage, dripped to the max, and getting awarded by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, I want it to be because I “Did The Right Thing” and put the hard work in, not because I forced it to happen.

This way, I know I’ll have made Spike proud.

Malcolm “Mack” Walker, 16, is a junior at North Atlanta High School who just got accepted into NYU Tisch’s Summer Filmmaking Workshop and has set up a Go Fund Me to help him get there this summer.

This story was published at VOXATL.org, Atlanta’s home for uncensored teen publishing and self-expression. For more about the nonprofit VOX, visit www.voxatl.org.