Familiar Echoes: 1918 Atlanta And The Spanish Flu

Volunteer nurses from the American Red Cross tend to influenza patients in California in 1918. While the two pandemics are nearly 102 years’ worth of scientific advances apart, Atlantans of 1918 were faced with a situation familiar to Atlantans today with coronavirus.

Edward A. "Doc" Rogers / Library of Congress via AP

Closed schools and businesses. No religious services. Face masks in public. That has all happened before; it was more than a century ago when Georgia and the world faced the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic.

It is considered the most severe pandemic in modern history. One-third of the world’s population was infected, and 50 million people died, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

While the two pandemics are nearly 102 years’ worth of scientific advances apart, Atlantans of 1918 were faced with a situation familiar to Atlantans today.

In early October 1918, the City Council, Atlanta’s health officer and its board of health, “which was comprised of doctors in Atlanta, made the recommendation that all schools, libraries, theaters, movie houses, dance halls, churches and other public gatherings be closed for two months,” said Louise Shaw, curator of the Centers for Disease Control’s David J. Sencer Museum.

(The museum has been planning an exhibit about the flu in the 20th and 21st centuries.)

Shaw said the ordinance followed national health guidelines from the period.

The country’s surgeon general “recommended to all state health offices they consider enacting what we are now calling social distancing measures,” she said, which some officials at the time called “breaking the channels of communication.”

But like today, federal officials left specific measures up to state governments.

Georgia, in turn, left the decisions up to its local municipalities like Atlanta. (Gov. Brian Kemp, with some recent exceptions, has also left most restrictions in the hands of localities.)

Atlanta required all streetcar and vehicle windows to travel with windows open unless it was pouring down rain.

“Because they believed fresh air would help protect people from influenza,” Shaw said.

Many people, sick and healthy, were required to wear gauze face masks. Newspapers printed instructions about how to make your own, said Polly Price, professor of global health and law at Emory University.

She has been working on a forthcoming book about the ways epidemics have shaped American law and continue to pose challenges for disease control in democracies.

“That was thought to be an alternative to more extreme closures,” Price said of the masks.

“If you had to be out, if you had to get food, if you had to do things like that, you should wear a face mask.”

Health guidelines in 1918, like those of today, urged people to wash their hands and not touch their faces.

While scientists at the time weren’t able to identify the virus, nor treat it completely, they did have an idea of how germs spread.

“It’s common sense,” Shaw said. “And this is what the whole idea of breaking the chains of infection was, staying away from other people, not having contact, not touching one another. Washing your hands. There was enough understanding about germs being invisible and all around us at the time.”

A shortage of health care personnel also was an issue then, as it is now.

Kemp this week relaxed medical licensing regulations to allow doctors with lapsed licenses and graduate nurses who have not completed exams to treat patients, “to address critical healthcare needs in the weeks ahead.”

The Atlanta chapter of the American Red Cross was essential to the response in 1918, Price said, particularly in wartime when many doctors were serving in the military.

“They provided nurses, and those nurses would be dispatched by the health officer for the county,” she said. “For example, in the city of Atlanta, the health officer would get calls from other counties to please send nurses. And his response was very often that they didn’t have any to spare.”

Sometimes, Price said, those nurses would visit homes and do whatever sick families needed, like cooking meals.

“Without the American Red Cross nurses, the nation would have suffered much more than it did,” she said.

Two Weeks

But Atlanta’s business closure order did not stick for two months. Businesses reopened after two weeks. Schools did stay closed longer.

Then-Atlanta Mayor Asa Candler, of Coca-Cola fame, pushed back on the restrictions because he was worried about the local economy.

“It’s the same thing we’re feeling now because the economic impact was so profound on people,” Shaw said. “The businesses want to get open. It’s the same situation. The people working in these businesses weren’t getting paid. So the mayor wanted businesses opened as soon as possible.”

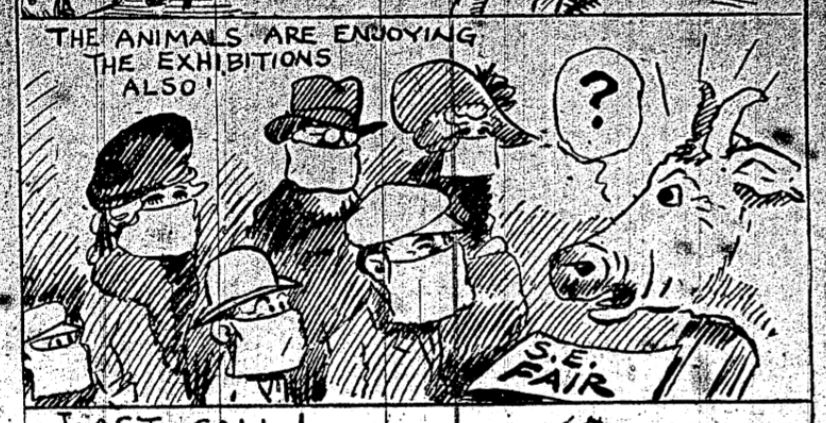

Looking back, it was a questionable public health decision. So was keeping open the Southeastern Fair at Lakewood, sponsored by the Chamber of Commerce.

“Everybody who attended the fair had to wear facemasks,” Shaw said. “They thought [since] it was outside, that it would be okay.”

An Atlanta Constitution headline trumpeted: “Carnival Spirit Pervades Crowd Masked At Fair,” documenting that 25,000 people attended the fair on one October day.

Another suggested the restriction would make the fairgrounds “resemble a Turkish harem, and the mask will prove as great a blessing to man as to woman” seeking to hide wrinkles or missing teeth.

Still, another tells of a protest by Atlanta theater employees upset that they had been discriminated against because while the fair was “allowed to run full blast,” they had been forced to close.

Railroads also remained open the whole time, Price pointed out.

The epidemic in Georgia seemed to wane briefly after businesses reopened, but spiked again a few months later in December until February.

A news report from mid-December painted a desperate picture of East Atlanta, which at the time had only one healthy doctor who was “sadly overworked” and receiving nearly 100 calls per day.

Shaw cited an official death toll of 875 but qualified it’s difficult to know how bad the Spanish flu got in Georgia, because health officials stopped reporting the numbers, and there was no test.

Scientists were not able to identify the Spanish Flu strain until 1933, she said.

Camp Gordon

The first documented Spanish Flu cases in Georgia happened at a World War I Army training camp, Camp Gordon, on the site of what is now the DeKalb-Peachtree Airport.

In late September, half of the personnel on the base were quarantined. By October, base leadership required all people to wear gauze face masks for weeks, and at one point, everyone was forced to bring their beds outside to sleep in the open air, 50 feet apart, in an effort to stem the spread of the respiratory disease.

On Oct. 4, the chief surgeon at Camp Gordon put out a request for 100,000 masks, if possible, before midnight that night. Red Cross volunteers, Price said, were able to meet that quota relatively quickly.

There was even a clash between the camp’s guards and 115 men tired of being quarantined who attempted to march out into Chamblee and Atlanta.

Michael Hitt, a local historian, said these strict measures made a difference at Camp Gordon. He said, based on his research, of the nearly 6,000 cases on the camp, just 166 people died.

The military response contrasted sharply with that of Atlanta, he pointed out.

“In Atlanta, the restrictions were kind of haphazard. ‘Well, you know we’ll get around to it. ‘We want our people to make money,’” he said. “But at Camp Gordon, they kept tight reins on this thing….It took strict measures, and they were in a military environment so they could do that.”

He said the tone from Atlanta in 1918 reminds him of the present-day reaction of some to the coronavirus: “if I can’t see it, it can’t hurt me. I feel fine. Therefore it’s not going to be an issue.”