The Georgia Legislature’s Human Resources Problem

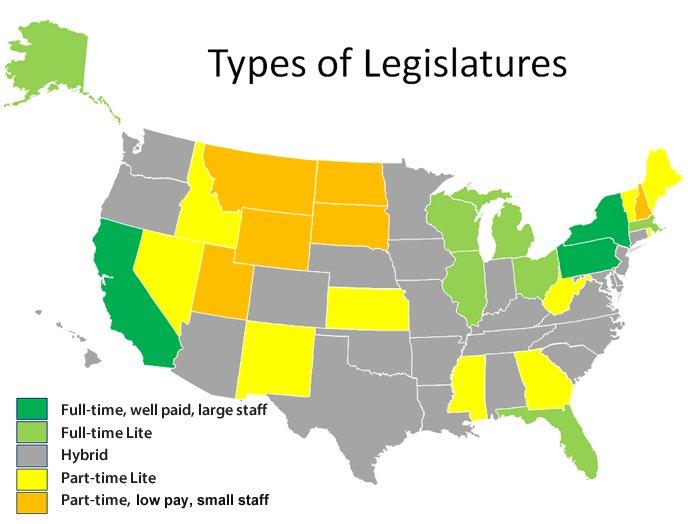

Courtesy of the National Conference of State Legislatures

The Georgia's Legislature's Human Resources Problem

Retiring state Rep. LaDawn Jones has a lot of reasons for leaving the Georgia Legislature. She’s the mother of a 6-year-old and a 9-year-old, both her parents recently passed away and she runs her own law firm.

One thing that might have kept Jones in the Legislature: more money.

“I could not dare ask my family to continue to make such a big sacrifice without that help,” she said.

On top of the low pay, Jones said legislators don’t have enough staffers to help them respond to constituents or figure out what a bill would actually do. She hired her own aide, but in the end Jones said she lost money.

“I absolutely believe that we need to increase the wage for legislators to keep up with the times,” she said.

Low Pay

Georgia’s general assembly has a human resources problem.

Many state lawmakers will travel hundreds of miles for the 40-day session that starts in January. They’re responsible for spending over $20 billion of taxpayer money, but they’re paid $17,000 a year, below the poverty line for a family in Georgia. Legislators are entitled to a per diem, and other reimbursements, but former lawmakers and lobbyists say it doesn’t add up to enough.

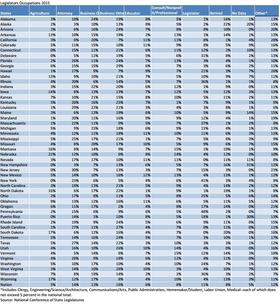

“There are very, very few working class people in legislatures,” said Neil Malhotra, professor of political economy at Stanford University. “This might have something to do with why a lot of legislation does not seem very friendly toward working class people.”

While Georgians with low incomes are at a disadvantage when it comes to writing bills or influencing policy, Malhotra said lobbyists have an edge at the state Capitol. In 40 days, lawmakers and a handful of staffers can’t get everything done on their own.

“If you are in session for a very small amount of time and don’t have staff resources, you don’t really write these bills,” said Malhotra. “The lobbyists kind of write the bills for you.”

Lobbyists, while representing special interests, are often resources for lawmakers because they know the details of complicated issues like healthcare or education.

Legislators bring their own expertise to the Statehouse too.

Recruiting Problems

Mike Dudgeon, chief technical officer at the video game company Hi-Rez Studios, is retiring from the Legislature after six years as a state representative. When it came to technology and energy issues, Dudgeon said his experience showed, and he could hold his own amongst lobbyists and other lawmakers.

“My expertise in technology meant that I could talk to my colleagues with authority about policy related there, and most of the time they would listen,” Dudgeon said.

Dudgeon called himself a “weird duck” in the Legislature, where many are lawyers, farmers or business owners.

He said the Legislature doesn’t have enough skilled professionals like him who work for the tech firms, and big corporations that dominate metro Atlanta. It’s hard for those people to step away from their jobs for the 40-day session.

“If you go to your boss and say ‘Hey boss. I need to be gone for three months out of the year, are you okay with that?’ Most bosses are going to say, ‘What are you talking about?’” Dudgeon explained.

Dudgeon is leaving the Legislature because it was keeping him from his work and his family.

“Some people suggested that I sort of do the phone-it-in thing, and keep my seat in the Legislature, and just do the bare minimum. Just go down and vote,” said Dudgeon. “But I just can’t do that; it’s not my personality. If I’m going to do anything, I’m going to do it well.”

More Money, More Problems

People like Dudgeon are in high demand in lawmaking and the business world. Malhotra looks at it this way: to get the best people, you’ve got to pay them more, or you end up with less-qualified lawmakers.

“Not paying legislators is like a very penny-wise, pound foolish thing, given how much the government actually spends,” said Malhotra.

But simply paying more or lengthening the legislative session might not solve the problem.

Both retiring Reps. Dudgeon and Jones worry a big raise for legislators could spawn more career politicians. They like the idea of citizen legislators, who take time off from their jobs to meet at the state capitol for 40 days, if they can afford it.

While compensation for state lawmakers is relatively low, some draw salaries in fields closely related to their work in the Legislature. Others make up for years of low pay in the Legislature once they retire by quickly jumping to consulting and lobbying firms where compensation is much higher.

Legislative leaders don’t seem interested in a raise.

“I’m not in favor of increasing legislative pay,” said Senate President Pro-tempore David Shafer. “I don’t know that anyone serves in the general assembly because of the pay, and I don’t know that we would attract a better legislator if the pay were higher.”

“People don’t want to pay politicians more money because they don’t like politicians very much,” said Malhotra.

Nationwide, Georgia is behind in legislator pay. Smaller states like Wisconsin, Michigan, and Massachusetts all pay their lawmakers more. Michigan lawmakers make more than $70,000 per year.

Meanwhile, Georgia’s population continues to grow, putting even more demand on state lawmakers.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))