Habitat Corridors Could Help Animals Adapt To Climate Change

By Craig ONeal [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Parks and natural areas can be like islands for wildlife, surrounded by rivers of roads or seas of development. And as the climate changes and temperatures rise, those islands are changing, too.

Plants and animals will need to move in order to keep living in the conditions they evolved to live in. And to do that, they’ll need to be able to island-hop to higher elevations or higher latitudes. Doable for birds, perhaps, or seeds that travel on the wind. Tougher for, say, a gopher tortoise.

A study published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences looks at how well-connected islands of habitat are, and finds that while there is a fair amount of connectivity in the western U.S., the eastern part of the country – including the Southeast – has much less. The paper, written by a Georgia Tech professor, also finds that some of the greatest gains could be made here in the South.

‘Like Frogger’

Islands of natural areas can be connected by what scientists call habitat corridors, paths that allow animals and even plants to either cross or travel around farms, roads or cities.

“Like Frogger, right?” said Jenny McGuire, a spatial ecologist at Georgia Tech, and lead author of Monday’s paper, referencing the video game where a frog tries to cross a busy street. “You know, your frog makes it across one out of four times if you’re pretty good at it.”

With a bridge, the video game would be a little less fun, but the frog would probably live.

Habitat corridors come on all scales: some cross a single highway, others are vast; for instance, one project aims to connect Yellowstone National Park to Canada’s Yukon.

With temperatures and habitats changing with the climate, corridors are one way that species can adapt, by moving to a cooler place.

“There’s a broad appreciation that plants and animals may need to move as the climate changes,” said Chris Field, director of the Department of Global Ecology at Carnegie Science, who was not involved in the study. “And there’s a broad appreciation that having the landscape chopped into units, especially where there are large areas that are dominated by humans, either urban areas or agriculture, can make it very difficult for plants and animals to move.”

Connected Enough?

So corridors can help. And one island connected to another is good. But if both islands have pretty much the same temperature range, and that temperature is going up, species could still end up stranded as the climate for which they evolved leaves them behind.

McGuire looked at how far species could travel with habitats as connected as they are now, and what future temperature ranges they might be able to reach. In the South, she found that, for the most part, there aren’t many corridors that would allow species to keep up with their climates, but there is potential to make improvements.

“By connecting up some of the natural areas, particularly moving from the coastal regions into Appalachia, or into the Ozarks, then we can really serve a lot of land area in the East,” she said.

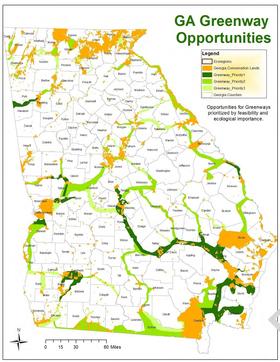

Georgia Corridors

There are some large corridors in Georgia already. The Altamaha River corridor stretches more than 40 miles. Marshes connect most of the coast. And there are even bigger goals: Georgia’s draft State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP) proposes connections across the state.

“It shows a vision of connecting up even the Appalachians to the coast and to southwest Georgia and on to Florida, Alabama, South Carolina and Tennessee,” said Jason Lee, who works on endangered species at the state Department of Natural Resources. “So it’s really a regional approach. It’s an idea to have a landscape somewhere in the future that’s connected across the Southeast and beyond.”

The idea isn’t just to use completely protected land to do it. The state works with landowners to find ways to support wildlife even on working land, and also to conserve privately-owned natural areas.

Georgia’s corridors are an important piece of the state’s efforts to protect wildlife, Lee said. Some species just naturally need big ranges, like black bears.

Corridors also help keep genetic diversity high, by connecting otherwise isolated populations to each other. That comes in to play with the red-cockaded woodpecker, he said. And in the future, they could help Georgia’s plants and animals weather climate change.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))