Georgia teachers discuss handling topics involving race under the state's 'divisive concepts' law

The death of Tyre Nichols in Memphis at the hands of police officers and recent protests around a proposed police training center in Atlanta have grabbed national headlines recently, raising questions about race and power.

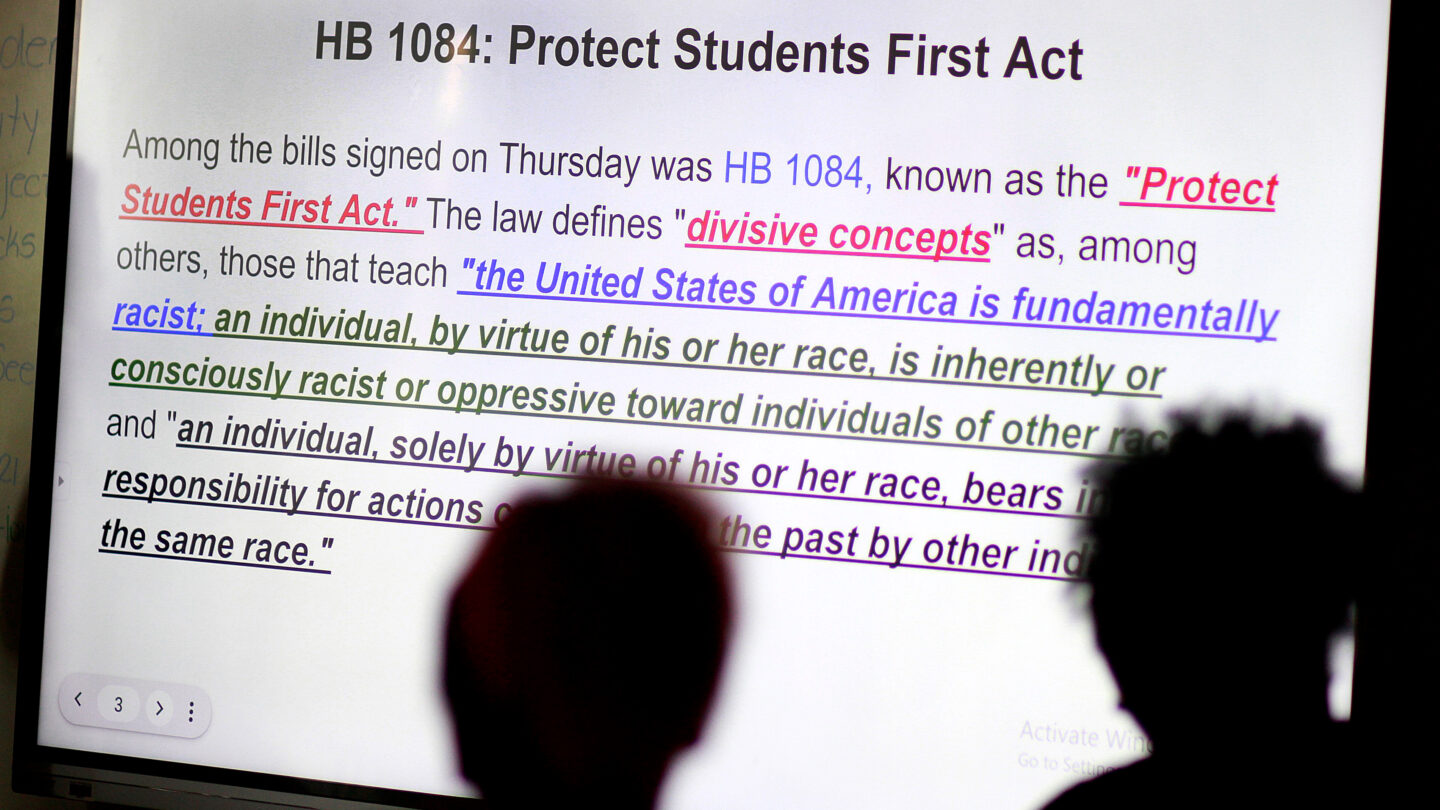

Georgia teachers, who want to discuss current events like these with their students, have to do so within the confines of a new law. The so-called “Divisive Concepts” law bans teachers from discussing nine topics related to race.

They include: not teaching that one race is superior to another and teaching that the U.S. is a fundamentally racist country. Critics have said that the law’s language is so vague that it could have a “chill effect,” meaning teachers will avoid any conversation around race for fear of breaking the law. The law’s supporters say it shouldn’t interfere with the accurate teaching of history. Rep. Will Wade, R-Dawsonville, sponsored the bill in the House last year.

“This bill does not limit an educator,” Wade told the House education committee. “What it does is empower parents to ensure that kids and children in our schools of all races are not pitted against each other.”

The law’s critics have said the language is vague, which could confuse educators. But some teachers say they can’t worry about the legal consequences of having open discussions with their students.

“If I talk about putting sugar in grits, I could get in trouble with that law,” says middle school Language Arts teacher Alison Cundiff.

Although Cundiff doesn’t teach history or social studies, she wanted to let her students know they could talk about Nichols’ death after the video was released.

“I mentioned that, ‘Hey, you know, I’m aware that this happened in Memphis, and I just want you to know that it hurts me that this happened, and if you want to talk about it, that’s ok, and if you don’t want to talk about it, [if] you want to focus on the assignment, that’s ok too,’” she says.

Cundiff is a white teacher working at a school that mostly serves students of color.

“The thing is, if a white educator doesn’t bring this stuff up at all or even acknowledge it or just tries to pretend everything’s normal, that’s been shown to be damaging to children of color,” she says. “Obviously, I don’t want to do that. I care about them, and I want them to know that I care.”

Under the statute, every local school board had to adopt a process for dealing with complaints from parents about educators who violate the law. The legislation outlines potential consequences for districts, including revoking state waivers for charter districts and allowing the state board of education to decide on repercussions for educators.

Paige McGaughey was told she would face the consequences from her school district in 2020 after she hung a Black Lives Matter poster in her classroom shortly after George Floyd’s death.

Schools were still remote at the time, and a parent of a student she taught saw the poster hanging behind her as she taught virtually. She soon got a call from the Gwinnett school district’s human resources department.

“I was told that it impacted my effectiveness as a teacher and that my Black Lives Matter poster was divisive and I needed to take it down,” McGaughey says.

Georgia’s divisive concepts law wasn’t in place at the time. Still, McGaughey says human resources implied there would be consequences if she didn’t take the poster down. She kept it up.

“I said in a respectful way that there was the First Amendment and I was not going to do that,” she says.

McGaughey says she mentioned Tyre Nichols’ death in class because she discusses current events with her students. She is also a white Language Arts teacher at a middle school that mostly serves students of color.

McGaughey says she teaches because she loves it, but she doesn’t need the job. That means she’s willing to stand up for what she believes in, she says, where other teachers might be intimidated.

Brian Westlake, a high school history teacher and Gwinnett County Association of Educators president, believes some teachers may avoid controversial topics because they don’t think school leaders would support them.

“I think most teachers would feel that we don’t trust administrators, in general, to back us up if there’s any pushback,” he says.

Some teachers said they felt supported by their administrations but didn’t want to speak on the record for fear of facing other consequences, possibly from their school district or the state.