Kenya Native’s Nonprofit Helps Refugee Women Rebuild Their Lives In Clarkston

Since 2006, Doris Mukangu has served as the founder and president of the Amani Women’s Center.

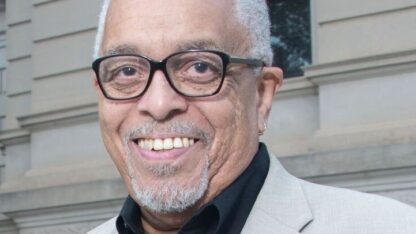

LaShawn Hudson / WABE

Doris Mukangu says her East African upbringing has helped fuel her passion and vision to empower women.

The Kenya native says her political and cultural understanding of the many challenges women face, both on the continent of Africa and in the United States, has uniquely positioned her to create a safe space for women fleeing from backgrounds of trauma and violence.

“The passion is driven by being a woman of African descent, from growing up in a culture where opportunities are not as available. And then coming here and knowing there are so many opportunities available,” says Mukangu, 45.

Since 2006, she has served as the founder and president of the Amani Women’s Center (AWC), a Clarkston-based nonprofit that provides educational programs, financial literacy, health workshops, and many other culturally tailored programs specifically geared toward helping refugee women.

“Amani means peace in Swahili,” Mukangu explains. “The idea behind Amani is a safe place where women can come to and get nurtured, empowered and be given tools to be self-sufficient. We have a holistic approach when working with refugee women and their families.”

For Mukangu, AWC’s mission to educate and empower women is not only a business standard, it’s personal.

In 1996, she moved from Kenya to the United States to continue her education. While on an educational visa, she studied medical technology at the University of Auburn in Montgomery, Alabama. After graduating in 2002, she relocated to Atlanta for a job at a medical clinic. After six years of climbing the corporate ladder, a volunteer opportunity at the DeKalb County Board of Health changed her career trajectory. She says she began learning about the city of Clarkston, which has one of the largest refugee populations in the state of Georgia.

“Refugees were arriving by the hundreds,” Mukangu explains. “They’d have to go through the DeKalb County Board of Health for medical screenings.”

While volunteering, Mukangu noticed cultural and language barriers hindered newly arrived refugees from taking full advantage of resources. She says there was a huge disconnect between refugees and health care providers.

“A provider was so upset because many of the refugees were not returning for their followup appointments,” says Mukangu. “I then asked her what language she left the message in. She told me English.”

Mukangu, whose native language is Swahili, began to use her expertise to translate and interpret for refugees and medical providers.

Soon after, a gravitational pull led her to branch out on her own. Within a few months, AWC was established.

Along with its unique programming and services, AWC operates a sewing academy at Memorial Drive Presbyterian Church. Instructors teach refugee and immigrant women how to make clothes, accessories and jewelry. The goal is to teach women skills that will help them become financially independent.

“I would say 90% of the women who participate in our academy are from African countries,” says Mukangu. The other 10% are from Burma and Nepal. The idea is not to close our doors to any refugee woman.”

Congo native Carmel Bahati is currently taking classes at the Amani Sewing Academy. The 25-year-old mother of three says she feels much closer to achieving some of her lifelong goals.

“I always hoped to have my own business, make my own clothes and help other people,” Bahati explains. “The people at Amani are truly interested in helping you. That makes me feel very happy.”

Upon graduation, students are gifted with their own personal sewing machines.

“The idea is to teach these women how to fish,” explains Mukangu. “They have different choices after graduation. They can start their own business, they can sew for one of the sewing factories we partner with, or we can sell their merchandise through Johari Africa.”

Mukangu says community-based organizations help play a critical role in helping AWC serve refugee women in Clarkston.

Speaking to “Closer Look” host Rose Scott at the February installment of WABE’s “Coffee Conversations” series, Mukangu said, “Refuge Coffee has been very instrumental in bringing folks into this neighborhood who would typically not come here and learn about refugees. Also, they are very generous in sharing their support base by inviting groups like us and others to their seasonal outdoor events that again adds to the story and allows us to meet people who we wouldn’t typically get to meet.”

Mukangu says she’s excited about the growth that’s happening in Clarkston, but she is also concerned about how the growth will impact refugees. She says she’s currently witnessing a second migration for refugees due to rising rent costs.

“I would say Clarkston provides a space where you can experience an exchange of cultures organically,” says Mukangu. “If you come with an open heart, you can receive a lot and learn a lot.”

As for the future of AWC, Mukangu says she hopes to continue serving refugee women by aiding them with the tools to rebuild their lives. She says her biggest hope is to eventually own a multipurpose space that houses AWC’s sewing academy, administrative offices and showroom. She also wants to purchase a van that can be used to help transport women and their families to their medical and social services appointments, community events and sewing classes.

“Our doors are always open,” Mukangu explains. “We have a vested interest in our community. The idea is to not close our doors to any refugee women.”