Texas Locomotive Gets Room With A View At Atlanta History Center

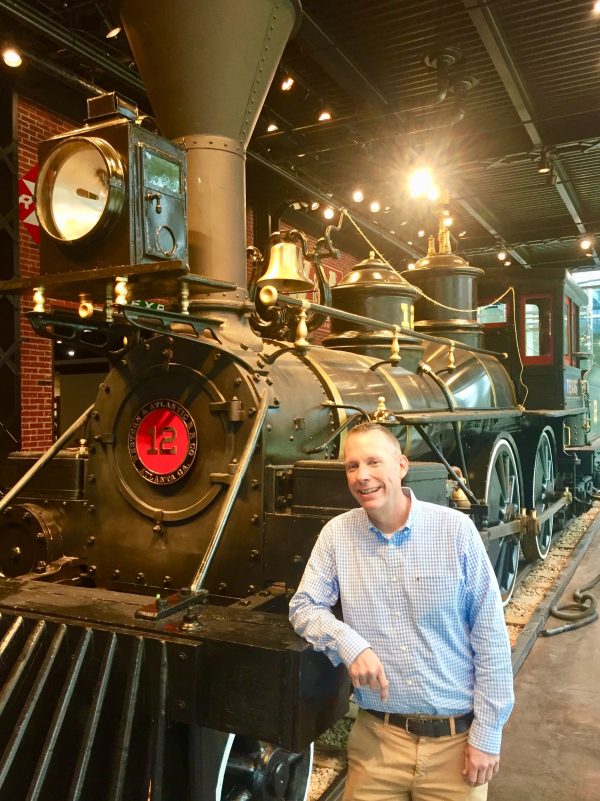

Jackson McQuigg, the Atlanta History Center’s vice president of properties, stands beside The Texas locomotive in the exhibition “Locomotion: Railroads and the Making of Atlanta.”

Atlanta History Center

One of the city’s longest-running attractions, the Cyclorama painting, is being readied for the public at the Atlanta History Center. And while the enormous painting and diorama are being installed for an opening in early 2019, its longtime roommate, The Texas locomotive, is now on display in the Atlanta History Center.

One of the remarkable things about this new exhibit of this very old locomotive is that you don’t even have to go inside the Atlanta History Center to see it. The history center’s president and CEO Sheffield Hale made sure of that.

“When they put it in here, I said, ‘I want you to be able to see it from West Paces Ferry,’” Hale says. “And you can, for free, 24 hours a day.”

It’s a bit of a change from The Texas’ old home.

Anyone who might have grown up going on school field trips to the Cyclorama in Grant Park might remember it being on display there. The locomotive and its tender car had to be basically excavated from the building in 2015.

“The logistical challenge was to get it out of the building,” says Jackson McQuigg, the history center’s vice president of properties. “Basically going straight through the auditorium, which involved digging a large hole, putting I-beams in the auditorium, and have them double as railroad tracks, put ‘em on edge, and away we went … got it to the end of the hole and picked it up with a crane and put it on a truck. In the rain, several days before Christmas 2015.”

That’s a lot of moving around for an engine that was last in service in the early 20th century. And being used to keeping a safe distance, both from trains and historic artifacts, I was surprised when McQuigg literally invited me aboard and into the cab of The Texas.

“One of the things that museums have been trying to do,” McQuigg explains, “is to make history more approachable. For most of its life, this engine was kept away from the public. There was this [attitude that] people should keep a respectable distance. Actually, people should have a respectable proximity.”

After being pulled out of a hole in Grant Park, the engine was shipped to the North Carolina Transportation Museum where it got an extensive year-and-a-half restoration by Steam Operations Corp.

“History comes alive when you can get close to it and you can step in the very footsteps where others did,” McQuigg says.

Some of those footsteps are more well trodden than others. For instance, most folks who know The Texas from its decades on display at the Cyclorama probably know of its involvement in what’s known as “the Great Locomotive Chase” during the Civil War.

“A group of Union spies were effectively caught in the Kennesaw area and run out of town by a group of Confederate pursuers,” McQuigg explains. The Confederates gave chase on The Texas for 87 miles.

“That’s just a brief blip in its 60-year service life,” McQuigg is quick to point out.

One of the advantages of having The Texas installed at the Atlanta History Center is the chance for further interpretation. To present the sensational along with the rest of its no-less-important history in a place where it can be put not just in the context of the Civil War but in its place in the greater history of the city.

As McQuigg and I spoke, a group of actors was rehearsing various characters and stories associated with The Texas to help literally bring history alive for visitors.

“Here we have all the artifacts from Atlanta’s past,” McQuigg says, “the paper orders that Gen. Sherman received to burn Atlanta, items from the civil rights movement, the Olympics… none of that would be here if not for the Western & Atlantic Railroad. They designated the terminus that became Atlanta.”

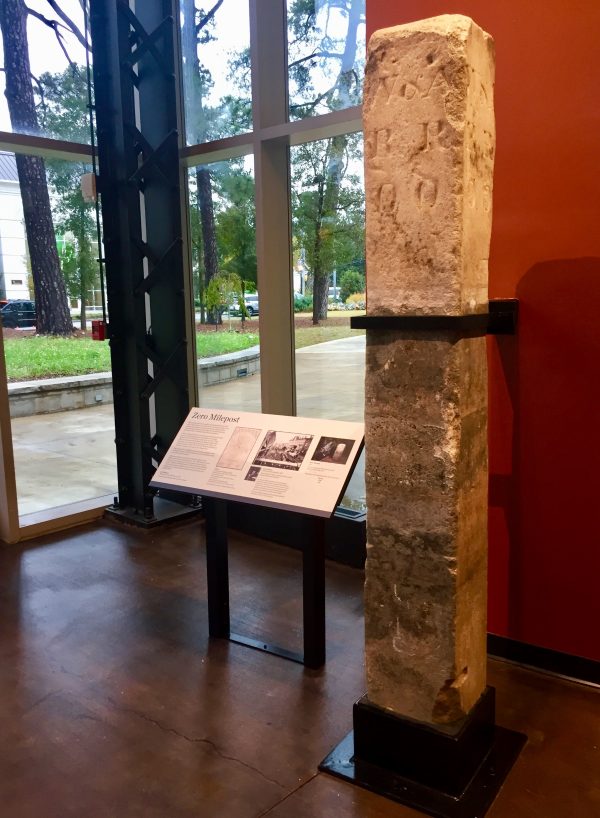

And speaking of that terminus, one of the other pieces of history joining The Texas in the atrium is what could be considered the origin of the city itself —the Zero Mile Post, the marble marker that was driven into the ground that marked the end of the Western & Atlantic line and effectively set in stone the placement of the city to come back in 1850.

I got to visit the post in 2011 in its original spot near the Georgia Freight Depot, underneath Central Avenue. It sat in a squat brick building that used to be a depot for the New Georgia Railroad in the 1980s. I ask Hale about that little brick depot today.

“It’s gone,” he replied. “It was demolished last weekend.”

While The Texas, the Cyclorama and all those artifacts that McQuigg mentioned unquestionably belong at the history center, it was the location of the Zero Mile Post that made it significant. I ask Hale about the thinking behind moving it.

“The whole point behind it was to be able to protect it and to put it in a place where it could be seen, enjoyed and understood in context along with The Texas and understand why Atlanta’s here,” he says. “I refer to these as our ‘Romulus and Remus artifacts.’ That’s why Atlanta’s here. It’s our origin story.”

Hale acknowledges that the original site is important. And that’s why the Atlanta History Center has taken GPS coordinates and plans on putting a replica post there along with a historical marker.

But I see what he’s talking about when he says that the history center is putting the post in context. Next to it, there is a photo of Union Station taken in 1887. The Zero Mile Post is visible there, but the scene is otherwise unrecognizable from the Atlanta that stands on the spot today. Union Station was a gorgeous, bustling train depot. Today, it’s a parking garage.

“It’s all been erased,” Hale says. “You can thank the automobile for that.”

Erased everywhere, that is, except inside this glass atrium, visible from West Paces and lit up at night like the Rosetta Stone.