Some Black South Georgians Hope Their Votes In The Senate Races Lead To A Fresh Start

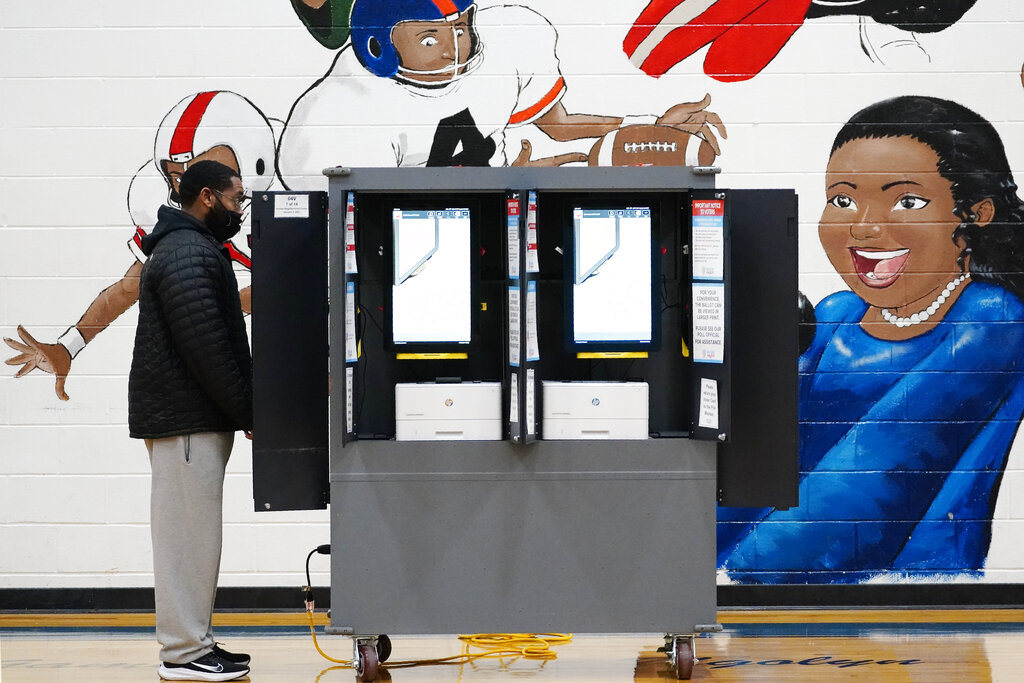

A person casts their vote during Georgia’s Senate runoff elections last week in Atlanta.

Brynn Anderson / Associated Press

Rev. Michael Ephraim Sr. and his more than 250 congregants remember when Dougherty County was a one-time epicenter of the pandemic in March. And they’re still waiting for COVID-19 relief.

“By the mere fact that people that are used to congregating can’t congregate, it’s on their minds,” Ephraim said.

Ephraim’s Bethel AME Church in Albany is now virtual. And the pandemic was one reason voters in Albany and the surrounding area cast ballots in the runoffs. Another was a chance to change the balance of power in the U.S. Senate. A third reason, Ephraim says, were attacks on Warnock that may have played a role in energizing Black churchgoers in South Georgia.

Black voters in Georgia showed up in record numbers to vote for Sens.-elect Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff. Both Warnock and Ossoff won seats in the U.S. Senate against Republican incumbents.

In a nationally televised debate in December, Kelly Loeffler referred to Warnock as a radical liberal. Her campaign also used snippets of sermons to make this point. Warnock is reverend at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta. And Ephraim says these ads were not only an attack on Warnock but on the Black church.

“You are calling us out of our name,” Ephraim said. “It’s almost like on the schoolyard where somebody talks about your momma.”

After the debate, a coalition of pastors signed a letter and called on Kelly Loeffler to stop her characterization of Warnock, as first reported by the New York Times. Loeffler said that her comments about Warnock were not about the Black church.

Ephraim says the Black church has always fought for racial justice. And describing it as radical is a perennial double standard. He says especially compared to predominantly white religious institutions that may advocate for the same issues.

For Carlton Hollis of Lee County, just north of Dougherty, he said he didn’t see Loeffler’s comments as an attack on the Black church at first. A congregant of Bethel AME, what ultimately motivated Hollis, 61, to vote in the runoffs were issues around racial justice, police reform and climate change.

“We gotta respect the environment, be better stewards of the environment,” he said.

He also wanted to see Democrats take control of the Senate.

“He’s been the party of no for a long time, and it was time to change that dynamic,” Hollis said of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell.

“For my community, it was Warnock versus Mitch [McConnell],” Ephraim said of Bethel AME. “It was Ossoff versus Mitch because Senator McConnell stood in the way of progression.”

Residents in Dougherty County, hard hit by the pandemic, he said, wanted to see more money for stimulus checks and other COVID-19 relief. McConnell denied a vote on a bill that included $2,000 stimulus checks.

Now that Warnock and Ossoff won, Ephraim’s grateful for the years-long effort to mobilize Black Georgians to vote.

“We can now preferably have a fresh start … and begin to heal our country,” he said.

Ephraim says he and his congregants want to return to some semblance of the life they had prior to March 2020.

____________________________________________________________________________

Behind The Story

Roxanne Scott produced this story as part of the America Amplified initiative using community engagement to inform and strengthen local, regional and national journalism. America Amplified is a public media initiative funded by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Earlier this year, producer Maria White Tillman led a conversation with congregants of Bethel AME Church on how residents in Albany were dealing with the pandemic. Roxanne Scott followed up to learn if the effects of the pandemic motivated residents to cast ballots in Georgia’s Senate runoffs.