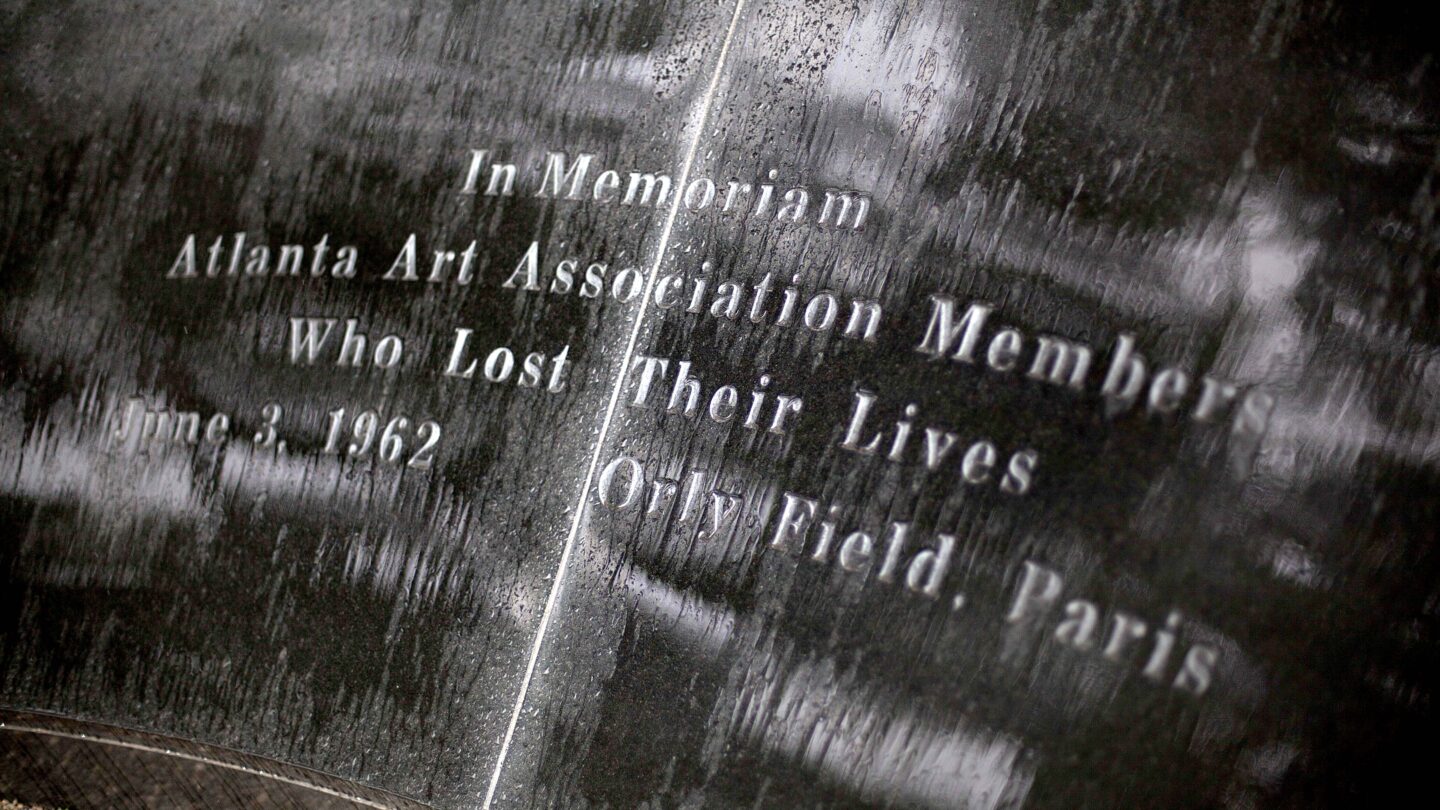

Rickey Bevington reflects on the 1962 Orly plane crash and the arts invigoration that followed

Today marks the 60th anniversary of the Orly plane crash in 1962.

It was then the world’s deadliest airplane accident, killing 122 people. A hundred and six of them were members of the Atlanta Arts Association, and an outpouring of sympathy from across the country resulted in millions of dollars donated on behalf of the lives lost.

Those donations led to the creation of the Memorial Arts Center, now known as the Woodruff Arts Center.

Two of those on board the plane were Betsy Bevington and Dell Rickey, the grandmother and great-grandmother of Rickey Bevington. Bevington is an award-winning journalist, president of the World Affairs Council of Atlanta and executive-in-residence at Georgia State University’s Robinson College of Business.

She joined “City Lights” host Lois Reitzes via Zoom to reflect on the crash that changed Atlanta forever.

Interview highlights follow below.

Growing up in the shadow of a great tragedy:

“It’s hard to know when I first learned about it. And when we say we didn’t talk about it, I think what we mean is, it just was too painful. It just was, and I think anybody who’s experienced really deep family trauma can relate to it, not being a casual dinner conversation,” said Bevington. “When I was about eight years old, my mother took my brother and I to France, and I remember her on the phone, back in the day of travel agents. She said we don’t fly in or out of Orly … I think that was the first time that I remember understanding the power of the Orly air crash, that my mother was going to make sure that her children were never going to fly in or out of Orly.”

Remembering Betsy and her influence on a creative family:

“Betsy, my grandmother, was a painter. She attended Wellesley [College] and I have one painting that remains of hers. There may be more, but nobody in the family has come forward with them. I would be surprised if there weren’t more. She attended Wellesley and she met my grandfather, very likely at a Wellesley-Harvard mixer as undergrads. And she was just from a very early age, very, very creative, and I know this because my father is extremely creative. He is a photographer in his retirement, but has always been passionate about photography. So what I know of Betsy’s love of the arts I often deduce from my father’s love of the arts, and my own sense of creativity as a journalist.”

An arts legacy carried on by Atlanta’s bereaved:

“This event took people’s breath away, much like Americans of a certain age can tell you exactly where they were when they learned that John F. Kennedy had been shot, Atlantans of that generation can tell you exactly where they were when they heard about that airplane crash,” said Bevington. “My mother tells me that five children in her class lost parents. So the impact on Atlanta was extremely emotional and traumatic for a whole community of people who, as we know, got to work raising money to create the Arts Center that the people who died had envisioned.”

“Every time the Woodruff Arts Center brings joy to someone or opens their eyes to the power of art — musical art, performance art, children’s education or just staring at a painting on the wall — that is the vision that my grandmother and great-grandmother had for the city. I mean, it can bring me to tears thinking that this is what has come of an awful tragedy,” Bevington reflected. “Every time I go to the Woodruff or just have a little bit of extra time in Midtown, I just go sit with them. And I talk to them and I say, ‘What would you think of all this? What would you think of Atlanta? What would you think of me?’”