Why The Supreme Court Is Hearing A 28-Year-Old Ga. Case

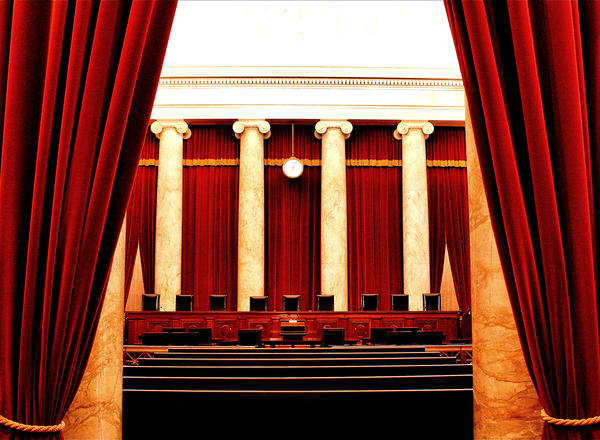

The U.S. Supreme Court has agreed to hear arguments in a 1987 Georgia death penalty case in which Floyd County prosecutors are accused of racially discriminating against prospective black jurors.

The nation’s highest court will decide the issue in the case of Timothy Foster, an African-American man sentenced to death by an all-white jury in the 1986 murder of 79-year-old Queen Madge White in Rome, Georgia.

Sarah Turberville is a senior counsel with the non-partisan Constitution Project, which studies death penalty cases like the Foster case.

She explained during an interview on “A Closer Look” why the U.S. Supreme Court is taking up the case now.

“A hundred percent of the people of color were removed from Mr. Foster’s jury pool.”

Turberville said the prosecution provided a number of explanations for why all the black potential jurors were removed from the pool at the time and the court ruled in favor of the prosecution.

“What the trial court at Mr. Foster’s actual trial didn’t have the benefit of is the trove of information that we now have that contains all the prosecutor’s notes during jury selection,” Turberville said.

Foster’s attorneys eventually obtained notes used at trial by the Floyd County prosecution in a 2006 open records request. The notes showed that the names of black jurors were highlighted, the word “black” was circled on jurors’ questionnaires, and the names of African Americans were also found on strike lists.

In court action over the case in following years, the Georgia Supreme Court sided with a lower court, ruling that ultimately prosecutors did not use the lists to make important decisions in the case and let the death penalty ruling stand.

The U.S. Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling in the case of Batson v. Kentucky in 1986, the year before Foster’s case, ruling it illegal to discriminate on potential jurors based on race.

The ruling did not offer much guidance on what would be a permissible race-neutral explanation for striking members of the jury based on race or gender.

“What Batson did was set out a kind of procedure that the courts could follow in determining if there was purposeful discrimination and, of course, purposeful discrimination on the basis of race is prohibited by the 14th amendment. So that would be the Constitutional issue that we’re looking at here in jury selection.”

The high court will hear Foster’s case when the new term begins this fall.

WABE’s Johnny Kauffman, Rose Scott and Denis O’Hayer contributed to this story.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))