Georgia veterans sickened by toxin exposure to finally get more care and benefits

Hundreds of thousands of Georgia military veterans have been exposed to toxic chemicals in war zones — exposure that made them sick. But for decades, the United States Department of Veterans Affairs did not recognize that most of the illnesses were caused by their service. That’s about to change, as the VA prepares to enact the biggest boost to veterans care in decades.

When Air Force Reserves veteran Marie Williams had trouble breathing after returning from Iraq, she had a feeling she knew why.

For her entire 2009 deployment, she was stationed near a massive open pit that burned day and night.

“Just like how you would have in your backyard where you put all your leaves or put all your junk in one pile and you burn it,” she said. “That’s why I kept asking questions. I’m like, what is in there? Is it hazardous chemicals that are in there? Is this stuff that we should be breathing? Like, is this going to kill me?”

Nobody she served with had answers that made sense, she said.

The military has commonly used so-called burn pits in war zones in Afghanistan, Iraq and across the Middle East to dispose of waste by setting it on fire with jet fuel in the open air.

What’s burned in the pits, some as big as football fields, is a long list that includes everyday garbage and food waste, chemicals, paint, plastics, metal, tires, ammunition products, even medical and human waste.

“Finally, something is actually being done without us having to go through hoops and jumps.”

Marie Williams, Air Force Reserves veteran

The 43-year-old Williams, who lives in the Atlanta suburbs, served two decades in the military before retiring in 2017.

She said the smoke from the burn pit on her base north of Baghdad was inescapable.

“It was my first breath of air each morning. You know, I’d wake up, go to my door and open it — it was the burn pit. That’s what you smelled,” Williams said. “Yeah that’s what you smelled.”

On the base, Williams worked in an area next to the hospital ER with a medical squadron, leading a team that received injured patients coming in by ambulance or helicopter.

When asked how she’d describe the smell, she responded immediately.

“Death. It reminded me of the patients that came in that were burned.”

The Department of Defense has since closed most of its burn pits. But it’s too late for the millions of veterans already living with their impacts.

Williams traces her lung symptoms to the poisonous burn pit smoke she breathed.

“To this day I’ll have a little coughing attack. Shortness of breath, sometimes wheezing,” she said.

This summer, Congress passed the PACT ACT. The full name of the law is The Sergeant First Class (SFC) Heath Robinson Honoring our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics Act.

Under the law, the VA must assume the illnesses experienced by Williams and other veterans who served near burn pits are caused by the exposure.

Until now, that link was open to interpretation by the VA, which historically denied most disability claims, saying more study was needed.

The long-awaited change also applies to Vietnam veterans’ exposure to the herbicide Agent Orange, and to veterans exposed to radiation.

In June, U.S. Sen. Jon Ossoff of Georgia spoke during a debate on the measure, telling his fellow lawmakers the PACT ACT will also help veterans whose claims were wrongly rejected in the past.

“This is about folks like Army Sergeant Jeff Danovich who fought in Mosul in 2004, where he lived just 100 yards from a burn pit,” Ossoff said. “But just two years ago, Sgt. Danovich was diagnosed with leukemia. And when he filed for disability with the VA his claim was denied.”

The Associated Press puts the VA’s burn pit denial rate at roughly 70%.

Now, the VA has added a dozen more cancers and another 12 conditions, including respiratory and pulmonary diseases, to its list of so-called “presumptive” conditions.

The expansion of presumptive conditions is expected to help an estimated 3.5 million veterans nationwide get disability benefits and treatment.

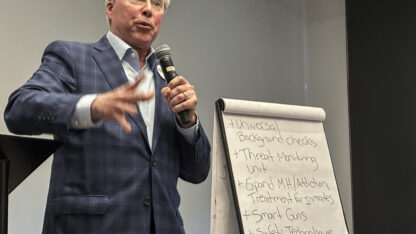

“I’m responsible for eight health care systems and the care for about 1.2 million veterans,” said Dr. David Walker, an Air Force veteran and psychiatrist who heads the VA’s Southeast Health Care Network that includes Georgia.

The state has approximately 270,000 veterans who currently get their health care through the VA. And Walker expects that at least another 30,000 veterans will enroll for VA care in Georgia as a result of the PACT ACT.

He waves off criticism from some veterans advocates who worry the already backlogged VA system isn’t ready for so many additional claims, pointing to funding available through the $280 billion PACT ACT to help the VA build capacity, including in claims processing, staffing and healthcare facilities.

“This law is also going to provide resources for the VA because it is anticipated that their workload is going to increase,” he said, “and basically because we want to serve all veterans who need to be served because of their exposure and to treat them.”

The law also includes resources to support federal research on toxic exposure.

Walker urges veterans to file a claim for PACT ACT-related disability compensation or apply for VA health care as soon as possible so they can get the help they need to heal from their toxic exposure.

That’s what Williams said she’s hopeful for.

“Finally, something is actually being done without us having to go through hoops and jumps,” she said. “I’ve deferred my health care for probably a year now, at least, because I was deterred.”

Medical referrals to needed treatments for her lung conditions weren’t going through, she said. It was demoralizing.

“And I think that’s how they get a lot of us because they know that we don’t want to go through all that just to make it a doctor’s appointment. It’s not worth the hassle mentally. We are depressed, we are going through our own mental issues, PTSD and whatnot, and having to call the VA for an appointment can sometimes take leaps and bounds,” Williams said.

VA officials are expected to begin screening veterans’ PACT ACT claims beginning in November, and all approved benefits will be backdated to August of this year.

To file a claim visit VA.gov/health-care/apply/application/introduction, or call the toll-free hotline at 877-222-8387.