With poll workers facing enormous scrutiny, Georgia is deploying a new tool to help keep them safe

Tight elections and baseless conspiracy theories mean election workers are facing enormous scrutiny, so the Georgia Secretary of State’s office is introducing a text-messaging application to help election workers flag threats.

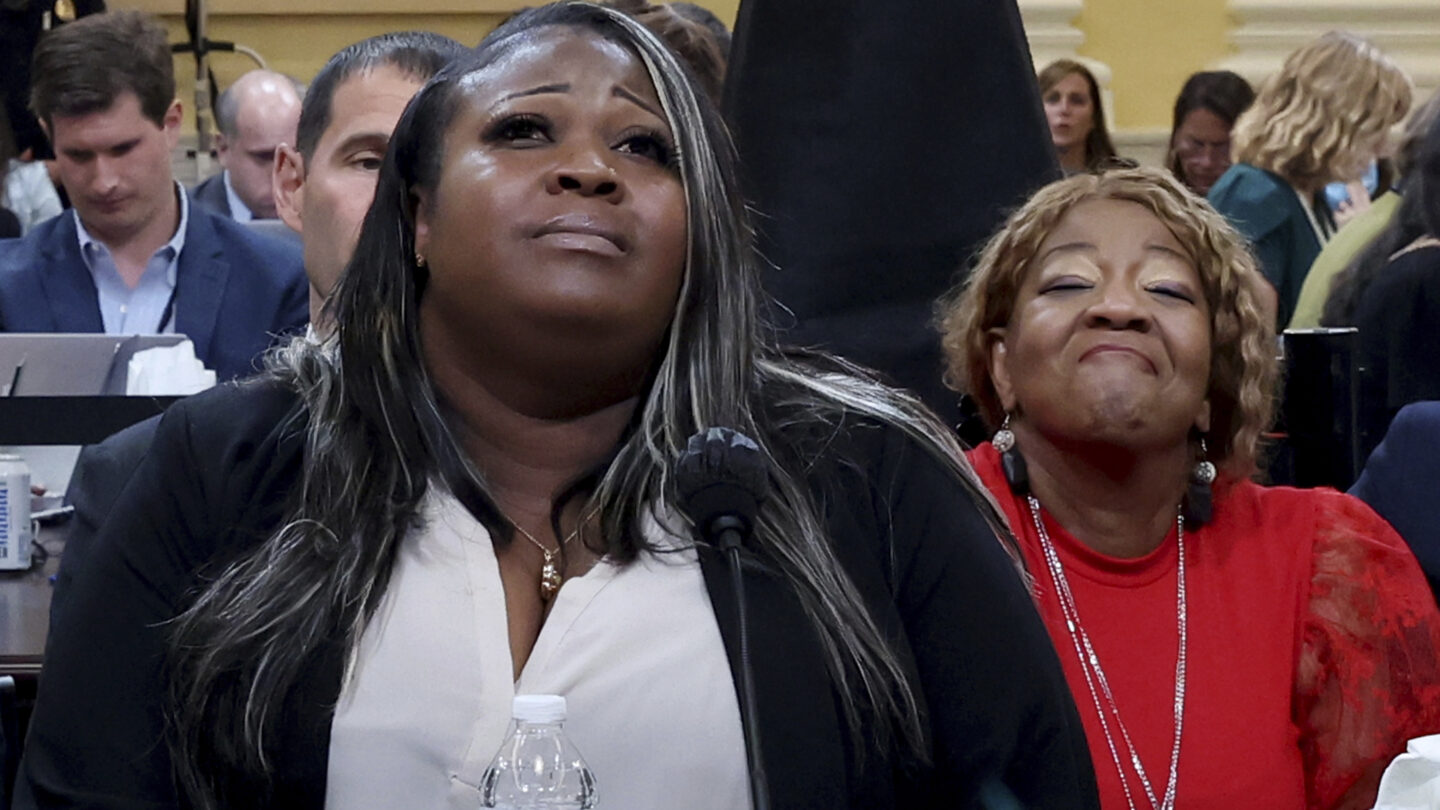

After the 2020 election, Fulton County election worker Shaye Moss said she no longer felt comfortable giving out her business card or even going to the grocery store.

For weeks, Rudy Giuliani, then-President Donald Trump’s personal lawyer, spread lies about widespread election fraud in Georgia. Those lies entangled Moss, who became the target of a barrage of violent threats.

“If I would have never decided to be an elections worker, I could have done anything else, but that’s what I decided to do,” Moss told the Congressional panel investigating the January 6th insurrection. “And now, people are spreading rumors and lies and attacking my mom.”

Moss’s story is an extreme example, but the U.S. Justice Department says election workers in states with closely contested elections like Georgia have been more likely to face threats.

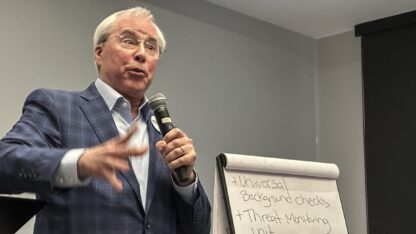

“Are the people here, who are using heated rhetoric, yes, but their reach isn’t as broad as you know, the president two years ago,” says Gabe Sterling, with the Georgia Secretary of State’s office.

Sterling says the climate in Georgia does not feel as tense now as it did after the 2020 election – at least not compared to other states like Nevada and Arizona where prominent candidates are running on false claims that the 2020 election was stolen from Trump. But he says the text-messaging app for poll workers is one new way election officials are preparing for whatever happens.

“The problem is, in this environment, it’s hard for a poll manager to discern someone who’s generally upset or someone who’s there to cause problems,” he says.

Deb Cox, the elections supervisor in Lowndes County, says the text system is set up to alert her office, the Secretary of State’s office and the local sheriff.

“It’ll make the poll workers feel better, too,” she says. “Because there’s a little bit of anxiety out there, looking across the United States, with some of the incidents that have occurred. So that allays some of their anxiety as well knowing they’ll have something that will get an instant response.”

Election officials and experts acknowledge that a safety app is just one tool. What it won’t fix is disinformation and a political climate that spurred hostility toward election workers in the first place.

Jennifer Morrell, a former election official who now serves on the National Task Force on Election Crises, says many veteran election officials have left the profession, and those who remain have had to devote energy to defending the integrity of the last election while trying to plan for the current one. She is also monitoring efforts to recruit election conspiracy theorists to serve as partisan poll watchers.

“My fear is that an innocent mistake or even something more normal, like long lines or the delayed opening of a polling location or a longer than expected time to report election results, will somehow be used to further undermine the work of these election professionals,” she says.