Georgia To Overhaul Prescription Drug Monitoring Program

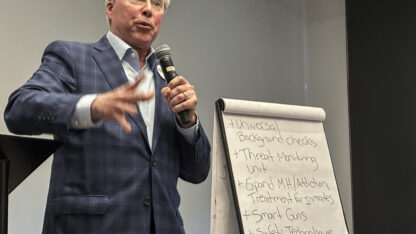

Alison Guillory / WABE

An audio version of this story

To Rick Allen, the way Georgia currently monitors prescriptions for drugs like hydrocodone or oxycodone has some problems.

“I have been threatened numerous times with going to jail, contempt of court,” said Allen, who leads the Georgia Drugs and Narcotics Agency.

Allen’s agency houses the state’s Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP), a statewide online database that tracks prescriptions for some drugs, like potentially addictive painkillers, with the goal of flagging people who are abusing or diverting the medication. In July, Georgia’s PDMP will get a major overhaul to fix what Allen said are gaps in the state’s 3-year-old program.

PDMPs are one of the top tools states employ to catch illicit use of prescription drugs. According to the National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws, 49 states have set up such databases, with Missouri being the lone holdout.

But every state’s PDMP works differently, depending on how each state wrote laws setting it up. In Georgia’s case – and why Allen says he’s sometimes threatened with incarceration – only a doctor or pharmacist can see the database. Anyone else who wants to get the prescription information has to file a search warrant in Fulton County, even federal officials from the Drug Enforcement Agency or Office of U.S. Attorneys who suspect someone is selling prescription drugs. Without that warrant, Allen says he can’t give federal agents the data.

“They would just jump up and down, and it was very plain and clear in the law what we had to do,” Allen said. “I just said, ‘Give me a nice prison cell.’”

Allen said he’s just following Georgia law, which, he added, has other problems, too.

As Georgia’s law is currently written, doctors and pharmacists can only use the PDMP to help decide whether to prescribe potentially dangerous narcotics or fill someone’s prescription for them, respectively. They can’t warn another doctor or pharmacist if a patient appears to be getting multiple prescriptions for those drugs.

Most doctors also aren’t required to sign up for an account on the PDMP, only those who run pain clinics. For those who do use the system, the data could be old, as pharmacists have up to 10 days to update the PDMP. That data also can’t be shared across state lines or with law enforcement without a warrant.

“We’re extremely limited at the moment of what we can look at it, if anything,” Allen said, adding that each month about 1.6 million prescriptions are entered into Georgia’s PDMP. “We have to rely on what we’re told.”

Updating The Law

Nationally, drug overdoses now kill more Americans than car accidents. The same statistic holds true in Georgia. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates more than 1,200 people fatally overdosed in 2014, a 10 percent increase from the previous year.

With the number of overdoses ticking up, the Georgia Legislature this session successfully passed legislation to beef up the state’s prescription monitoring.

One of the biggest changes is that doctors and pharmacists will soon be able to have licensed staff in their office check the PDMP, rather than having to do it themselves.

“Now we’ve taken that burden off the physician, who can now say to someone in his office, ‘I’m going to delegate this job to you. I want you to look up … next day’s patients, and do a run-through and see if we have anybody that looks like they’re getting into trouble,’” said Rep. Sharon Cooper, who sponsored the bill.

Under the updated law, prescription data will be tracked for two years instead of just one. Doctors and pharmacists will now be able to inform law enforcement of potential abuses they spot. And no longer will a search warrant be the only means federal and state law enforcement have to access that data.

Cooper said the main objective of the changes is to get more doctors and pharmacists to use the system. Right now, about 5,000 doctors have signed up for accounts on the PDMP. By comparison, in 2010, the Georgia Board for Physician Workforce estimated there are more than 20,000 physicians in Georgia.

“What we’re hoping is that if we catch people early and alert another physician, like the person’s family physician, that we can get early intervention before that person ends up moving from an opiate to heroin,” Rep. Cooper said.

Despite the changes, the state’s prescription drug monitoring program will still fall short of the CDC’s recommendations.

Doctors still won’t be required to check the database before writing a prescription, and pharmacists will still have 10 days to update the database. The CDC recommends the latter be done within a day.

Cooper said if the recent changes don’t significantly increase use of the PDMP, those requirements could be something the state will look at in the future.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))