Restacking The Deck: Gender Discrepancies In Academic STEM Fields

Al Such / WABE

In the fields of science, technology, engineering and math, often referred to as STEM fields, men can outnumber women 5-to-1.

Nationally, “women are becoming increasingly prevalent in each new cohort of doctorate recipients, earning a majority of all doctorates awarded to U.S. citizens and permanent residents each year since 2002,” according to a 2015 report published by the National Science Foundation.

But only 24 percent of the total share of STEM jobs in the nation belong to women, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce.

“The deck is stacked against women,” Kennesaw State University professor Dr. Scott Nowak said.

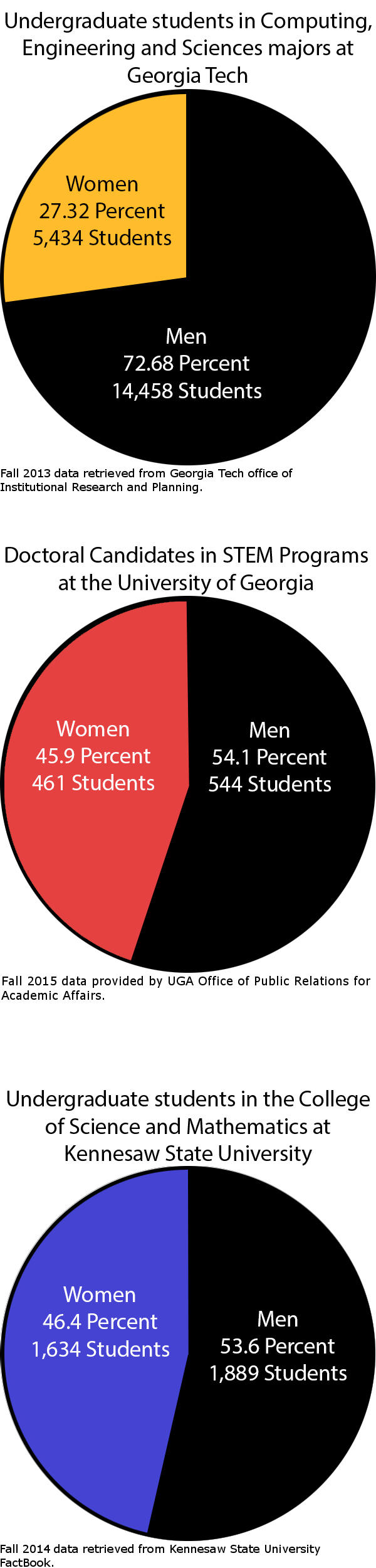

University System of Georgia schools share many similarities with the trends across the United States.

Misleading Statistics

On a surface level, the gender discrepancy in STEM fields might seem coincidental. Statistics provided by the University of Georgia for fall 2015 show that 53 percent of all STEM majors at the University of Georgia are women, but individual majors within STEM programs at the university tell a different story.

Some majors are relatively equal in terms of gender distribution. Animal and dairy science shows that 47 percent of its doctoral candidates are female and 53 percent are male. But in majors such as computer science, 82.5 percent of its doctoral candidates are male while 17.5 percent of its students are female.

Fixing Georgia Schools

Georgia Tech professor Dr. Carol Colatrella works with the Georgia Tech Center for the Study of Women, Science and Technology to recruit and promote women at the institute in STEM fields. The ratio of men to women in STEM majors has improved during the 23 years Colatrella has worked at Georgia Tech.

Years ago, “women had to be three times as good [as a man] in math to get into the institute,” she said, “but over time that formula has changed.” The requirements have been altered so that a female student is judged more fairly than they once were, and the changes have benefited the institute, Colatrella said.

“There’s been a real push to get more women, and incoming classes in the past couple of years have had about 44 percent women entering,” Colatrella said, “so there’s a real hope that we can move more toward the right kinds of proportions.”

At Kennesaw State University, biology majors Megan Barnett and Dinahlee JuPierre said they believe any discrepancy they do notice in their classes is a coincidence nowadays.

Overall, according to fall 2014 numbers, Kennesaw State teaches more female students than male, and there are only 255 fewer women than men at the College of Science and Mathematics. Due to this fact, JuPierre and Barnett said they believe their experiences as women in STEM majors may differ from the norm.

At the University of Georgia, Dr. Timothy Burg said it is frustrating to see such a discrepancy in departments such as electrical engineering. In order to remedy that, Burg has hosted many events that encourage young people to join STEM fields.

“We need to have a system that addresses as many points as we can,” Burg said. ”We need to counter all the negative points women are getting in their lives with positive points.”

Burg said that some of the difficulty in recruiting women into STEM fields lies in the message recruiters are putting out. They aren’t sure what works and what doesn’t, and it will be difficult finding that balance.

In the meantime, researchers such as Dr. Jessi Smith at Montana State University are working on studies and programs to help recruiters repair their implicit gender biases.

Implicit Biases

Smith published a 2015 study that found that providing university hiring board members with materials that teach them about implicit bias made those board members 6.3 times more likely to offer positions to women.

Smith said that these implicit biases are a hindrance to women and other underrepresented minorities attempting to enter STEM fields.

Project Implicit at Harvard University defines an implicit stereotype as a stereotype “that occurs outside of conscious awareness and control.” For example, even if you may say explicitly that men and women are equally good at math, it is possible that you implicitly associate math with men without knowing it.

Essentially, what you say or think consciously may be very different from what you think subconsciously. Project Implicit helps people identify their implicit biases.

In one study, students who were members of underrepresented minorities were reported to get better grades and take more science classes when they were shown the bigger-picture benefits of their work.

These types of biases are likely a major contributor to the gender gap in STEM majors. What society perceives as an “appropriate” job for a woman is, subconsciously or not, embedded in the perceptions of young women, their peers and their parents, and that works to drive women away from STEM fields, or toward specific fields that mesh with gendered perceptions.

“When you think ‘professor,’ you think of an old white guy who looks like Einstein,” Smith said.

Smith said that these biases are not the fault of any specific person – we all have them and our world view is shaped by and shapes them.

Therefore, it is important to train people in recognizing and dismantling the biases they have, she said.

Family and Career

Kennesaw State University professor Dr. Lisa Ganser said she witnessed firsthand the barriers women face in some STEM fields as she progressed through her career as a biologist, eventually earning a Ph.D. in biology and neuroscience.

While she was studying herpetology, she felt like she was the “other” in her group.

“For a long time, I was the only female in my cohort,” Ganser said. While she said she loved her field, Ganser also said that she was the target of harassment and mistreatment in the lab. As a young scientist new to the field, she wasn’t sure of a safe and appropriate way to handle the way she was being treated.

“If one of your heroes or mentors harass you in the field or say something a little bit off, it doesn’t sit so well. Is it OK to say something back?” Ganser said.

Ganser said she also lacked a supportive mentor with whom she identified for much of her education and early career. She had to learn on her own what was an appropriate way to handle harassment in the field and in the lab.

Shortly after committing to a Ph.D. program, Ganser found out she was pregnant with her second child, and Ganser said she was unsure how to handle all the responsibility. It didn’t help when her adviser called her to say that everything would be OK – she could take six weeks and she had to come back.

Six weeks to recover and then to get back into the swing of things, go back into the field and do her teaching assistant work “was a really tall order,” she said.

“You have so much anxiety because you have these expectations of finishing a large document, a large body of research,” Ganser said. “You have to go in and do your job, and I had to come back home and be a mother and be a wife and a chef – the entertainer – and it was really hard.”

In addition to raising a child while trying to progress in her career, Ganser said she felt there were different expectations placed on her by her colleagues solely due to her gender.

“There seems to be an expectation in academia that if a female is going to have a family or is pregnant that it’s going to take her away from her job and they’re less desirable as a candidate,” she said.

For a woman in a STEM career, it could be easy to feel like personal desires must be pushed to the wayside because the career does not wait. Some women wait until they have finished with post-doctorate studies to consider families, and by that point they may not have the chance to start one, Ganser said.

For women who do choose to have a family, it may be hard for them to balance family and career, although Ganser said the balancing act is worth the effort.

Nowadays, Ganser shares a hallway with other professors, some of whom she said she considers very good friends, but she can still feel like “the other” at times.

“I’m the one with two X chromosomes,” Ganser said. “Look around – there aren’t many of us around.”

Married, With Children

Drs. Kristine and Scott Nowak are both professors at Kennesaw State University, and they have the unique experience of balancing two academic careers at the university with the responsibility of taking care of their three young children.

They say they have found a happy balance, but Scott Nowak said he has found that his colleagues may perceive him differently for picking up the children from school than they may perceive his wife doing the same thing.

“Unfortunately, society tends to forgive the woman for going to get the kids but the man is expected to be there,” Nowak said.

Kristine Nowak said that her career worked out in such a way that she was able to create a healthy work-life balance with her husband and three children.

“It just so happens that he’s tenure track and I’m not,” Nowak said. “At the end of the day, someone has to leave at 5 to get the kids, and if you’re tenure track you don’t get to leave at 5.”

Scott Nowak said that the balance between familial pressures and the requirements of a STEM career could push women toward choosing either a career or a family.

“There are pressures that many women feel they may need to take a year or two off to raise a kid,” Scott Nowak said. “For many women that enter into a faculty position, there are considerations you have to have in place that, depending on the school, they may allow women to take a couple extra years on the tenure clock. But there are undoubtable pressures that are placed on them, and a part of that is society.”

Ending Inequity

“Inequities that exist in science reflect those that exist in society, broadly,” Georgia Tech professor Mary Frank Fox said in an email, “and because of the power and influence of science, inequities that exist for women in science shape those in the society at large.”

The people working to close the gap may still feel they have to fight an uphill battle against mentalities that aren’t explicitly stated by society, and most aren’t even conscious. Nevertheless, the researchers and professors working to close the gap said they hope that the gap will close sooner rather than later.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))