Federal Policy Puts Chimpanzee Behavioral Studies In Doubt

Courtesy of Dr. Charles Menzel / Georgia State University

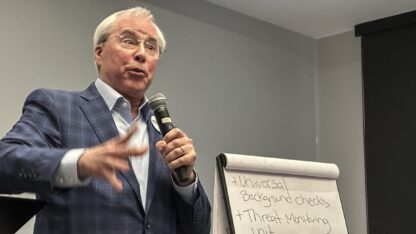

Professor Michael Beran puts on a lab coat to work with Sherman, one of Georgia State University’s three chimpanzees. The primates live in a jungle gym-like enclosure, which includes indoor and outdoor areas, at the university’s Language Research Center in south DeKalb County.

In the indoor section, Beran invites Sherman over and sets up a test using carrots and bananas; the sight of the latter makes the chimp grunt loudly. Beran covers up each food with a differently colored container and has Sherman pick which one he wants.

Beran is a psychologist who compares chimps’ abilities to ones that develop in humans, like decision-making skills and self-control. This is the kind of research he’s been doing at Georgia State for 20 years.

Recently, though, he and others who study chimps’ minds and behaviors have been a little worried.

“What’s concerning for us is that we think that the narrative is a little skewed right now,” Beran said. “And we’re trying our best to remind the public about why this research is important.”

Last year, the National Institutes of Health, the biggest funder of chimpanzees in studies, stopped supporting a different kind of science on chimps – biomedical tests, like vaccine trials. That decision has led the federal agency and other labs to decide to retire hundreds of chimps from labs and into sanctuaries.

While animal rights activists have praised these developments, the changes have concerned behavioral scientists. If eventually there are no chimps left in labs, their work as it’s done now can’t continue. And Beran doesn’t think people realize how much we’ve learned about the animals through that work.

“If 30 years ago, we did what we’re doing today,” Beran said, “we’d be sitting here with almost no knowledge of the mathematical capabilities of these animals, the social and cooperative behaviors they do.”

Many of the things that the public has learned about chimps through science documentaries – that chimps have communicated with sign language or that they’re one of the few animals who recognize themselves in mirrors – were discovered in labs, behavioral scientists will point out.

Allyson Bennett, professor of psychology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said that these findings, which give insight into the complexity of chimpanzees, can help us even recognize what is ethical to do with the primates.

“Science is one of the primary ways that we make progress in understanding the animals and making breakthroughs that can assist in their care,” Bennett said.

These behavioral studies benefit not just our knowledge of the chimps, Bennett said, but the chimps themselves. And in that way, stopping the studies could be a great loss for the animals, she said.

“It’s certainly less troubling than invasive biomedical research, if you’re talking about risk and benefit,” said Jeffrey Kahn, a bioethicist at Johns Hopkins University.

Kahn helped develop a report, which persuaded the NIH to end the use of chimpanzees in biomedical research. While he recognizes the worth of behavioral science, he said you still have to take into account that these are sophisticated creatures.

“There are many interesting and important things that can be learned from studying chimpanzees. The question is are those interesting and important things important enough to justify using these animals in a research setting,” Kahn said, adding that he doesn’t have the answer.

Those in the animal rights community see less of an issue. Even if all chimps are moved from labs into sanctuaries, that’s no reason for behavioral scientists to worry, according to Kathleen Conlee of the Humane Society of the United States.

“We shouldn’t be looking at this like as, ‘Oh we can’t do anything or learn anything more about chimpanzees or do any behavioral research,’” Conlee said.

In her view, researchers just need to take their work to sanctuaries. Just last month, in fact, Chicago’s Lincoln Park Zoo and the sanctuary Chimp Haven announced a partnership to continue certain kinds of behavioral research on chimps.

Though, Conlee admits that scientists entering sanctuaries might have to adjust to new rules, like only studying chimps through observation.

“I think they’re just going to have to get creative. It’s a new day and there are more opportunities,” Conlee said.

Scientists voice a little more skepticism about those opportunities. But what bothers Beran is the assumption that chimps can’t be comfortable in research settings, like the one at Georgia State, where the animals’ participation in cognitive studies is voluntary and, he says, beneficial to them.

“Our first thought before we can do any science is whether the animals are in the right environment to show us their best skills,” Beran said. “So in some sense what the public wants – which is chimps that are well cared for – is exactly what we want.”

He said, for now, Georgia State plans to keep learning about their three chimps where they are. They’re now waiting to see if the NIH will continue supporting their work through grants. Even if the funding does come through, though, their animals are getting old. Sherman, for example, is in his forties, and the average chimp doesn’t live much longer.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))