After Famous Atlanta Frog’s Death, Groups Work To Save Others

Alison Guillory / WABE

A famous frog died at the Atlanta Botanical Garden in September.

He was famous because he was the last-known member of his species. Humans don’t usually witness the extinction of a species firsthand. Usually it happens in the wild, when no one’s watching. But what was probably the last Rabbs’ fringe-limbed treefrog lived in a glass tank at the Atlanta Botanical Garden, and his death, and the likely extinction of his species, made national news.

This one frog’s death highlights a global crisis for amphibians.

Lone Survivor

“When I first met that frog it was one of two that were left,” said Mark Mandica, executive director at the Atlanta-based Amphibian Foundation. He cared for the frog when he worked at the Botanical Garden.

“Checking on him every day, making sure everything was all right,” he said. “’Can I get you a cricket?’ Anything like that. But just knowing that he’s most likely the last one, and when it died that that species would be extinct was very emotional.”

This one lonely survivor was known by the nickname Toughie, though the people who cared for the frog said that they didn’t really use that name; it was more a media thing.

The frog was one of several collected from the wild in Panama in 2005. Zoo Atlanta also had a few; their last one died in 2012.

Killer Fungus

The Panama work was a rescue mission. The Botanical Garden and Zoo Atlanta went there to collect species that were threatened by a fungus known as chytrid that’s killing frogs around the world.

“Chytrid is a fungus that affects the skin of amphibians,” said Leslie Phillips, the amphibian specialist at the Atlanta Botanical Garden. “Since amphibians breathe through their skin, they absorb water through their skin. It basically thickens their skin where they’re unable to respire, to absorb water, and so essentially they end up suffocating.”

Hundreds of species of frogs have gone extinct or are on the brink of extinction because of this fungus, including the Rabbs’ fringe-limbed treefrog, which was last heard in the wild in 2007 and is now presumed to be extinct.

Some species of frogs aren’t affected by chytrid. Some can carry it, but not get infected. But for the frogs that are susceptible, chytrid has been a disaster.

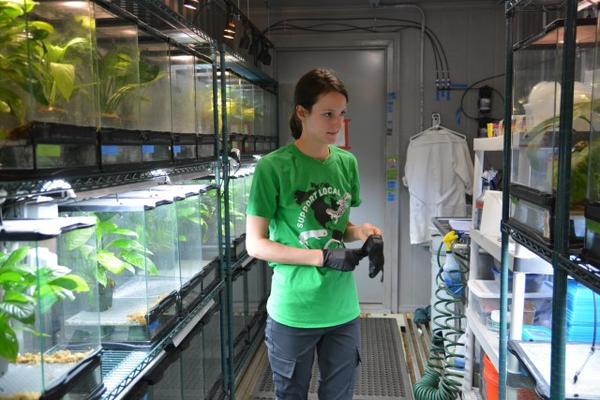

The Botanical Garden is still working to protect frog species with a tool called a frogPOD, which is a modified shipping container. There’s one frogPOD at the back of the Botanical Garden, behind all the public exhibits.

“The idea of this is that a shipping container is a way of having a quarantined and isolated area, and it’s cost effective too,” Phillips said.

Inside the shipping container there’s a little room for handwashing and taking off shoes, to make sure no one tracks in any contamination. Then behind another door is a room that is lined wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling, with tanks holding frogs. They are species from Panama that were collected on that same 2005 expedition.

Phillips pointed out one of her favorites, a mustard yellow frog with “horns” that look like Mr. Spock’s eyebrows.

“Horned marsupial frog. I just think they’re so charismatic, such an interesting frog,” Phillips said.

Changing Tactics

Scientists are no longer trying to eradicate the fungus, because it’s too widespread, Phillips said. Now the focus is on just trying to help amphibians survive it. FrogPODs could help, she said.

Phillips is setting up two in Honduras right now.

“Frogs will be collected from the wild, treated for chytrid, and then released back into the wild,” she said.

They’ll gather infected tadpoles, soak each one in a medicated bath, then raise it to adulthood and release it back into the wild. The hope is that they can keep enough frogs alive for long enough, so that maybe evolution can kick in when they’re released and get a chance to mate.

“At that point it’s kind of a numbers game,” Phillips said. “Hopefully, in terms of natural selection, you start to see frogs that are able to resist it better.”

There are similar projects in other places. In California, scientists are immunizing mountain yellow-legged frogs, which have been hard hit by chytrid.

“Ultimately the solution to this is evolution,” said Roland Knapp, a biologist at University of California, Santa Barbara, who works on the California project. “We just hope evolution moves fast enough.”

Ambassador For Amphibian Conservation

Rabbs’ fringe-limbed treefrogs never bred in captivity, so they didn’t have a chance to adapt. That’s why the frog at the Atlanta Botanical Garden was likely the last.

“His story caught the attention, relatively speaking, of a lot of people,” Mandica said. “I was proud to know him. He was an ambassador for amphibian conservation, for sure.”

And not everyone’s completely given up on that species. Zoo Atlanta is working with the Amphibian Foundation to support experts in Panama, who hope they can find survivors.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))