Mitchell County: How The Rural Ga. School District Beats The Odds

mitchell county school district

The Mitchell County school district is located in the town of Camilla, Georgia, about 200 miles south of Atlanta. The region is small, rural and poor. It also lacks industry. Despite those challenges, the schools there are starting to beat the odds.

They’re doing that, in part, by employing some unique methods for instruction and engaging parents.

Mitchell County is a 90/90/90 school district. That is, at least 90 percent of students are minorities; at least 90 percent come from low-income homes; and at least 90 percent of those students are meeting or exceeding state standards.

However, the student success piece hasn’t always been high.

There’s A New Principal in Town

The 2016-17 school year was officially Robert Adams’ first year as district superintendent. He came to Mitchell County in 2005, when he was hired to be principal of Mitchell County High School. That year, just 39 percent of students graduated. The valedictorian needed remedial help in college.

“When I came, the big people in town first said, ‘What did you do to get sentenced here?’” Adams says. “’We’re praying for you. You’ll never change that school.’”

Adams says there was a culture of low expectations across the district. He says it was common back then for students to be promoted to the next grade even if they weren’t ready.

“They’re leaving here and they don’t have the skill set,” he says. “They can’t have the SAT, ACT score to go to the next level. That they were able to be passed along without really doing the work, they don’t have the work ethic. So for them, it’s, ‘OK, I’m here. Now where do I go?’”

There were other problems, Adams says. For example, the high school didn’t offer some basic classes.

“When I first got here, we didn’t teach algebra,” he says. “We did pre-algebra, concepts of algebra, applied algebra, nobody took real algebra. Nobody took geometry, biology one, biology two. Nobody took chemistry. Nobody took an honors class. There weren’t any. That minimum was all it took. ‘Just get me by. If I get a 70, I’m happy.’”

Adams went into education after retiring from the Army in 1995. He was excited about the prospect of teaching high school.

“I don’t know that young people today understand the responsibilities of being an American citizen and the privileges that we really do have,” he says. “I’ve traveled all over the world. I said, ‘If I can come and be a part of that and help change, this would be awesome.’”

The Numbers Don’t Lie

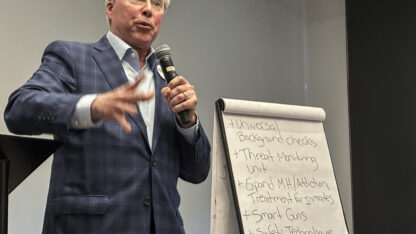

Adams is focused, serious and self-deprecating. He refuses to take credit for the district’s success. Instead, he attributes the success to his administration and teachers.

However, since Adams has been there, Mitchell County High School’s graduation rate has gone from 39 percent to 88 percent. This year, 25 percent of students graduated with associate’s degrees in addition to their diplomas.

Those students participated in the school’s “Move on When Ready” program, which allows advanced students to take college-level courses in high school. The first year, students take introductory courses at their high school. But during the second year, they board a bus and travel 35 miles to Bainbridge State College for class.

Because many of the them were first-generation college students, Adams knew they might need help navigating the Bainbridge State campus. So, he asked guidance counselor Lori Brinkley to help.

“Mr. Adams asked me, ‘I want you to get on the bus and ride with them every day and teach them how to be a college student,’” Brinkley says.

So she did. Brinkley helped students learn how to manage their time, meet deadlines and solve problems that come with being a college student.

“I just basically was there, visible, letting them know, ‘OK, if class starts at 1, you need to be there at 10 minutes until 1,’” she says. “I would just be there to keep them on track and suggest to them, ‘OK, you have a good hour and a half before the next class. This would be a good chance to go to the library and knock out that paper instead of going to the gym.’”

Brinkley, Adams and teachers in the Mitchell County schools know not every student will opt for college. So recently, the district has beefed up its career course offerings to help prepare students who want to enter the workforce after high school.

Students can choose from a number of programs. There’s an on-site medical clinic where they can take classes from registered nurses and become certified nursing assistants. They can get teaching experience in a pre-kindergarten class housed at the high school and earn a certificate to be a preschool teaching assistant. Students interested in agriculture can learn how to grow, harvest and sell produce in the school’s hydroponics house.

“We sell to local businesses,” says Alan Brown, a student adviser for the school’s chapter of Future Farmers of America. “We sell to the school cafeteria, the school restaurant, which is taken on by the culinary arts program, and we sell to basically anybody in the community who wants to come.”

However, Mitchell County’s accomplishments aren’t just the result of innovative course offerings. Teachers have also had to change their thinking and accept a new teaching philosophy.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))