Is A Sales Tax Hike A LOST Cause In Atlanta?

The metro area still faces many infrastructure problems only money can solve. If Atlanta’s next mayor sees a sales tax increase as a way to do that, Georgia State University’s Laura Wheeler says it might be a tough sell.

Pixabay Images

If you were to rewind Atlanta’s clock back five summers, you’d find Mayor Kasim Reed campaigning hard — not for re-election, but instead for a penny hike to the area’s sales tax.

“If we’re successful,” Reed said of a transportation referendum during a July 2012 press conference, “we’ll move the equivalent of 72,000 cars each day from our roads.”

The prospect of $7.2 billion over the next decade to fund 150+ transit projects brought together leaders from municipalities big and small, each making the case for a “yes” vote. In exchange, politicians promised constituents they’d experience an unraveling of Atlanta’s infamous traffic gridlock and other transportation woes.

But the referendum had its share of detractors, including some unlikely allies — the tea party and Sierra Club, for example. Democratic state Sen. Vincent Fort, who’s now running for Atlanta mayor, walked door to door in southwest Atlanta telling everyone who answered why she or he should vote down the proposal.

“This is going to be a tax on your groceries and your medicine,” he said to an elderly woman dressed in a housecoat.

For myriad reasons, voters in the Atlanta metro region fiercely rejected the “T-SPLOST,” as it came to be known (The acronym stands for Transportation Special Purpose Local-Option Sales Tax). It failed by a 2-to-1 margin.

But last November, Atlanta voters did a complete about-face and passed not one, but two, transportation-related referenda. Combined, they added nine-tenths of a cent to the city’s sales tax rate. That brought it to 8.9 percent and gave the city one of the highest sales taxes in the U.S.

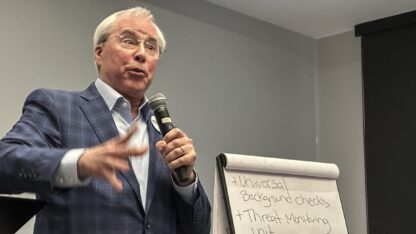

The now-familiar T-SPLOST is just one of many voter-levied sales tax options available to fund everything from the filling of potholes to the construction of a new government building, says Georgia State University senior researcher Laura Wheeler.

“We have, in Georgia, a whole portfolio of local option sales taxes. And SPLOST is one of these,” she said. “We also have a LOST, a HOST, and Atlanta has a MOST (Local Option, Housing Optional and Municipal Option). Oh, and don’t forget ELOST (for education) and in Fulton, DeKalb and now Clayton counties, there’s a MARTA tax, too.”

All those combined translate into a bevy of funding streams for local and state governments.

Take those $100 Nikes you have your eye on at Lenox Square. Pull the trigger and buy them, and you’ll have to fork over an additional $8.90 in sales tax. Broken down, that equates to:

- The state of Georgia getting $4 (The money goes to the general fund, and accounts for about 30 percent of the overall state budget.)

- Fulton County getting another $3

- $1 for MARTA

- $1 to fund an ELOST, split between Fulton County Public Schools and Atlanta Public Schools)

- $1 in LOST money, which helps fund every city in Fulton County. Each gets a proportionate cut based on their respective populations.

- The city of Atlanta claiming another $1.90

- $1 to fund sewer improvements (MOST)

- 50 cents in additional MARTA funding

- 40 cents for transportation (T-SPLOST)

Despite that chunk of revenue, the metro area still faces a lot of infrastructure problems only money can solve.

If Atlanta’s next mayor sees SPLOSTs as a way to do that, GSU’s Wheeler says it might be a tough sell. Although there’s no magic number where voters cry wolf, Wheeler noted “as the [sales tax] rate increases, it does make it harder to make [the] case.”

There are other factors working against a future sales tax hike. Competition, for example. If a purchase is big enough, and the savings justify it, consumers will cross borders to buy in adjacent counties, Wheeler said. The fact that Cobb, Gwinnett, and Cherokee counties each have a 6 percent sales tax will “put downward pressure on the Atlanta voters,” she said.

For Georgia Tech transportation and planning guru Catherine Ross, the likelihood of Atlanta’s next mayor wooing voters to sign up for another penny at the registers “depends on what [officials] do with the one we just passed,” she said.

If politicians stick to their promises and demonstrate what Ross called a “good use” of the money, then voters might be willing to vote in favor of another SPLOST.

That’s if lawmakers under the Gold Dome allow it.

Turns out Atlanta is already over the max when it comes to SPLOSTs —Georgia law caps the total sales tax rate at 8 percent. But Atlanta’s elected officials successfully convinced their colleagues to pass an exception, opening the door to the city’s current 8.9 percent.

There’s no reason to believe the next mayor can’t do the same.

Atlanta voters are preparing to elect a new mayor and replace nearly half the City Council. In this moment of transition, WABE is exploring “The Future of Atlanta.”