Georgia’s Behavioral Health Centers Say Resources Are Limited

Highland Recovery Center in Jasper, Georgia, serves about 20 men in a residential treatment center for substance abuse disorders.

Elly Yu / WABE

Chris Craft has struggled with alcoholism for about three decades. He had been drinking since college, but in his 40s, he said he started experiencing the consequences. He lost his job and his marriage, and he started getting into legal trouble.

“I picked up a DUI charge. I had a shoplifting charge,” Craft, 54, said. “There was a while there in Georgia where you couldn’t buy alcohol on Sundays, and I was so addicted to having that in my life every day that I would steal it. I would shoplift.”

Craft is one of 20 men at Highland Recovery Center in Jasper, Georgia, where he’s in a six-month residential program for people recovering from substance abuse disorders. Craft has been here since September when he had a relapse over the summer after four years of being sober, he said. Over Labor Day weekend, he was arrested for a DUI.

Craft has also been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, meaning he has a dual diagnosis of a mental illness and substance abuse disorder. He said he would turn to alcohol when he felt anxious, bored or depressed.

“I was kind of drawing to alcohol to make up that deficiency – almost like I was self-medicating myself,” he said.

He said at Highland Recovery Center, he’s learned a lot about his own addiction as a disease. Here, he speaks to a counselor daily and sees a psychiatrist on a regular basis.

“They’ve been really very good in helping me understand exactly what’s going on from a physiological and kind of a mental standpoint, and that’s the first time I’ve really had treatment that covers those areas,” he said.

But treatment centers like these that treat people at no cost are limited. As Georgia continues to deal with the opioid epidemic, those who work with mental health and substance abuse patients say the need is much greater than the help available.

Highland Rivers Health covers 12 counties in northwest Georgia. Besides residential recovery centers like this one, they offer counseling and other programs for people with mental illness, addiction and intellectual disabilities.

“We are, I would say, at capacity,” said Melanie Dallas, Highland Rivers Health’s CEO. “Right now, the most difficult thing for us would be growth – we’re at capacity in all of our facilities.”

She says it’s hard to keep up with the demand in the community. In all, they see about 16,000 patients a year.

“That really barely just touches the need,” she said.

For example, she said that the organization’s crisis stabilization units, which take patients going through a behavioral health crisis, are nearly full at all times.

“Within our system, we have 74 crisis beds. We usually run anywhere between 95 to 98 percent occupancy, so we literally have time to change the sheets before somebody else comes in.

Dallas says state funding dollars only stretch so far. The need is compounded by the opioid epidemic, counselors say. Treatment options aren’t keeping up, said Ryan Swartz, program manager for Highland Recovery Center.

“It feels like the epidemic is growing, and it’s exactly like trying to fix the crack in the Hoover Dam with a piece of gum,” he said.

Some lawmakers are looking at ways to get more money into the system. Since Georgia did not expand Medicaid coverage under the Affordable Care Act, the state pays for those who are uninsured. Dallas said about 40 percent of the people Highland Rivers serves are uninsured.

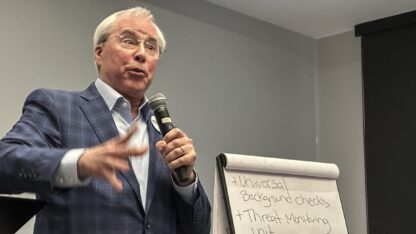

“We are paying for them with 100 percent state dollars, and we send all of our money up to Washington, D.C., so my answer is why not bring some of that money back home,” said state Sen. Renee Unterman, chairperson of the state Senate’s Health and Human Services Committee.

She said she’d like to see both federal and state dollars help people who are dealing with substance abuse disorders through what are known as Medicaid “waivers” to target certain populations, specifically those dealing with addiction.

“Why not bring our own money back and help take care of these hard, hard problems that we’re trying to resolve in this state? And one of them is the heroin and the substance abuse problem. These people need treatment. And the only way you can treat them is by putting more money into budget,” Unterman said.

For Craft, he said he’s now trying to work his way back into mainstream society.

“I would like to see many other treatment facilities made available like this because there are a lot of people out there, I think, that could benefit from it, Craft said.

He said he’ll be looking to interview for an entry-level job in the next few weeks.