How Georgia’s Republican Power Center Became A Voting Rights Battleground

Whether Hall County should provide voting materials in Spanish has been an ongoing issue. The Board of Elections has set up a committee to study the cost of providing ballots in Spanish and English, with the hope of finishing up later this year.

David Goldman / Associated Press

Ken Cochran said it was a mistake.

In April, Cochran was serving as acting chair of the Hall County Board of Elections. One of the two other members on the board – it was supposed to have five total members at the time – suggested Cochran add to the agenda whether the county should provide voting materials in Spanish.

Cochran said sure.

That decision sparked a monthslong struggle over the language on ballots in Hall County.

“I didn’t think at that time that it was going to be a vote,” he said. “I was hoping it was just a discussion.”

Per state law, the Hall County Board of Elections includes two appointees of the local Republican Party, two appointees of the local Democratic Party and a chair appointed by the county commission.

In April, there was no appointed chair. Cochran was the sole Republican appointee. The other two members, Gala Sheats and Kimberly Copeland, were Democrats.

The Democrats held the majority, and they moved the board to “proactively provide Spanish material for voters in Hall County, similarly to Gwinnett County,” according to official minutes of the meeting.

Cochran, surprised the issue went to a vote, said “no.” The Democrats voted “yes,” and the motion passed.

“I trusted them. That’s all I got to say. I trusted them,” Cochran said

Copeland and Sheats did not respond to WABE’s requests for comment.

In December 2016, the U.S. Census determined Hall’s neighbor to the south, Gwinnett County, must provide Spanish-language ballots under the Voting Rights Act. The law says in jurisdictions where more than 10,000 people or 5 percent of the total population are part of a particular language group, and they don’t speak English well, then the jurisdiction must provide voting materials in that language.

Hall hasn’t met that Census threshold yet, but at the April meeting, Sheats and Copeland’s votes indicated the county should provide ballots in Spanish, as well as English, anyway.

Hall County, foundation of Georgia’s GOP power structure, is in the state’s 9th Congressional District, one of the most conservative in the country. It’s also the home county of Republican Gov. Nathan Deal, Lt. Gov. Casey Cagle and state Senate Pro Tem Butch Miller.

The ongoing struggle over ballot language in Hall illustrates one of the challenges faced by Latino communities, many growing in Republican-dominated areas of the state, as they look to secure more political influence.

Changes In Hall County

Since she moved to Hall County five years ago, Michelle Sanchez Jones has seen the Latino population grow.

“A lot of the people from Atlanta and Gwinnett, they’re all moving up here. So, it’s definitely an influx of a more diverse community,” Jones said.

It’s especially visible on a stretch of Atlanta highway through Gainesville that is full of Latino-owned businesses, Jones said, labeling the area “Hall County’s Buford Highway.”

In 2000, Latinos made up 20 percent of Hall County’s total population, according to the U.S. Census. In 2016, it was up to 28 percent.

But Jones, a member of the Hall County Board of Elections recently appointed by the local Democratic Party, said Latinos don’t hold political influence to match those numbers.

Hall is one of four Georgia counties that’s part of a controversial program called 287(g) that allows local law enforcement officers to enforce federal immigration law.

The county commission is all white and Republican, and in the county seat of Gainesville, all but one City Council member is white.

The Georgia Association of Latino Elected Officials (GALEO) has said Gainesville’s election system, in which all council members are elected citywide instead of in more compact districts, dilutes the power of minority voters.

If council members were elected solely by voters in their districts, GALEO contends, more people of color are likely to be elected.

In Hall County, a lower percentage of Latinos than whites turns out to vote.

In the 2016 general election, about 66 percent of white registered voters went to the polls, compared to about 49 percent of all registered Latinos.

“I’ve heard many times people saying that they just don’t feel comfortable voting,” Jones said, “I think [Spanish-language ballots] would help incentivize people who otherwise would not feel comfortable to come out and cast a vote.”

Registered voters can get help reading the ballot on Election Day, but Sean Young, legal director with the American Civil Liberties Union of Georgia, said that can be a voting deterrent.

“If everyone were required to find help or someone to vote, that would be quite a burden for most of us,” Young said.

The New Chair

Since the Board of Elections’ April 2017 vote to provide Spanish-language ballots, another member was appointed by the Republican Party, and a board chair was appointed by the Republican-dominated county commission.

Tom Smiley’s appointment as chair drew criticism from Democrats because of his ties to Republican leaders in Hall County.

Smiley is lead pastor at Lakewood Baptist Church, where he said Republican Pro Tem Miller and U.S. Rep. Doug Collins attend. Smiley is a regular Republican donor. The online bio for Hall County Commission Chairman Ralph Higgins said the Republican “has been a member of Lakewood Baptist Church for 55 years, serving as a deacon, deacon chairman, adult and youth Sunday school teacher, and advisor on the building committees.”

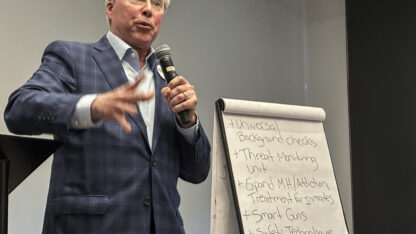

“I think because people recognize me as being a fair and unbiased person,” Smiley said.

This month, the board voted 3-2 to rescind the April vote to provide Spanish material for voters in Hall County.

The newly appointed Jones, and Sheats, the other Democrat, voted “no.”

Jones accused the Republicans on the board of rescinding the April vote simply to protect the GOP’s hold on Hall County.

“I can’t help but wonder if it’s because they’re scared of losing the power that they have,” Jones said. “They think that if more Latinos come out and vote that they will lose that power.”

By a large margin, Latino voters in the U.S. favor Democratic candidates.

Both the April and January votes are little more than procedural and perhaps symbolic because the Hall County elections administrators can’t produce or distribute Spanish-language voting materials without the commission appropriating the required funds.

“It was a lame duck, dead motion,” Smiley said of the April vote. “It’s not a political or partisan matter. It’s a matter of what’s right, what’s our job, and what’s not our job.”

The Board of Elections has set up a committee to study the cost of providing ballots in Spanish and English, with the hope of finishing up later this year.

Smiley said at some point, possibly soon, Hall County will be federally required to provide ballots in Spanish.

“The question is do the people of Hall County want to provide bilingual ballots before the mandate is required,” Smiley said. “I don’t know what the whole county commission will choose to do. They haven’t chosen yet to provide bilingual ballots.”