In The Races For Ga. Public Service Commission, More Attention — And Money

The Georgia Public Service Commission’s work includes oversight of the nuclear expansion of Plant Vogtle and the regulation of the state’s shareholder-owned utilities. The elections for the Public Service Commission don’t usually get a lot of airtime in Georgia, but the races are getting more attention — and more money – this year.

John Bazemore / Associated Press file

The elections for the Public Service Commission don’t usually get a lot of airtime in Georgia. That’s the quasi-legislative body that regulates Georgia’s shareholder-owned utilities, including Georgia Power. Their work includes oversight of the nuclear expansion of Plant Vogtle, which is years behind schedule and billions of dollars over budget.

Two of the five commissioner seats elected statewide are up for grabs this year, and, in part because of Vogtle, they’re getting more attention, and more money.

In one of those races, Democrat Lindy Miller has raised more than a million dollars, which is unheard of in a Public Service Commissioner race.

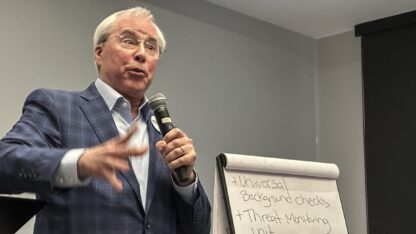

Her Republican opponent Chuck Eaton has been in office since 2006.

“From a fundraising standpoint, I’m the underdog for sure,” he said. “I think I’ve raised about a third of what my opponent has. I’m used to being in that underdog position.”

He’s raised about $270,000 this year. Miller, who owns a solar energy company, has raised more than Eaton in his last three races combined.

She said it’s because her message is resonating with people frustrated by their utility bills.

“People want to understand who makes the decisions that affect their everyday lives,” she said. “And I believe there are few seats as important as the Public Service Commission in impacting the everyday lives of people in this state because what is more personal than your budget as a family? What is more personal than the money that is taken out of your pocket?”

Dawn Randolph is the Democrat challenging incumbent Tricia Pridemore for the other commissioner seat.

Randolph actually ran unsuccessfully for the exact same seat back in 2006. She said this year feels “180 degrees different” and attributes it to increased awareness about the Public Service Commission, as well as Plant Vogtle. The project has highlighted “accountability problems with the Public Service Commission,” she said. “Everywhere I go people know about it, and they are very, very angry.”

Eaton disagreed: “Most folks are for [Vogtle]. Even the ones that have some reservations, when you sit down and talk to them about what it really means to be diversified, you get a lot of head nods and a lot of support.”

Where the funds for commission campaigns are coming from have also become a campaign issue. Miller and Randolph have refused to take contributions from people and entities connected to companies the commission regulates.

Incumbents Eaton and Pridemore received about two-thirds of those kinds of donations. That’s according to a September analysis from the advocacy group, the Energy and Policy Institute.

Per the analysis, about 3 percent of Miller’s contributions had industry ties, and Randolph had none.

“I think it’s different when you regulate an entity instead of passing law,” Randolph said about the need to keep those contributions off her list. “There’s a higher level of scrutiny, and you have to detach yourself.”

Eaton said he receives contributions from all kinds of people and groups, and all contributions are protected by the First Amendment.

“Unless we decide to eliminate the First Amendment and eliminate free speech, I don’t think it will change,” he said. “I think the one thing to keep in mind is if we’re talking about a conflict of interest, my opponent owns a company that will directly benefit from the decisions that she makes on the Public Service Commission.”

Miller has said if she’s elected, she’ll sell her stake in her solar energy company.

Bubba McDonald, chair of the Public Service Commission, said the industry-related donations are legal under Georgia ethics laws.

“The ethics laws are there. We don’t make the laws,” he said. “It’s very, very difficult to run a statewide race as a Public Service Commissioner.”