Rural Fulton County Offers Glimpse Of Georgia’s Digital Divide

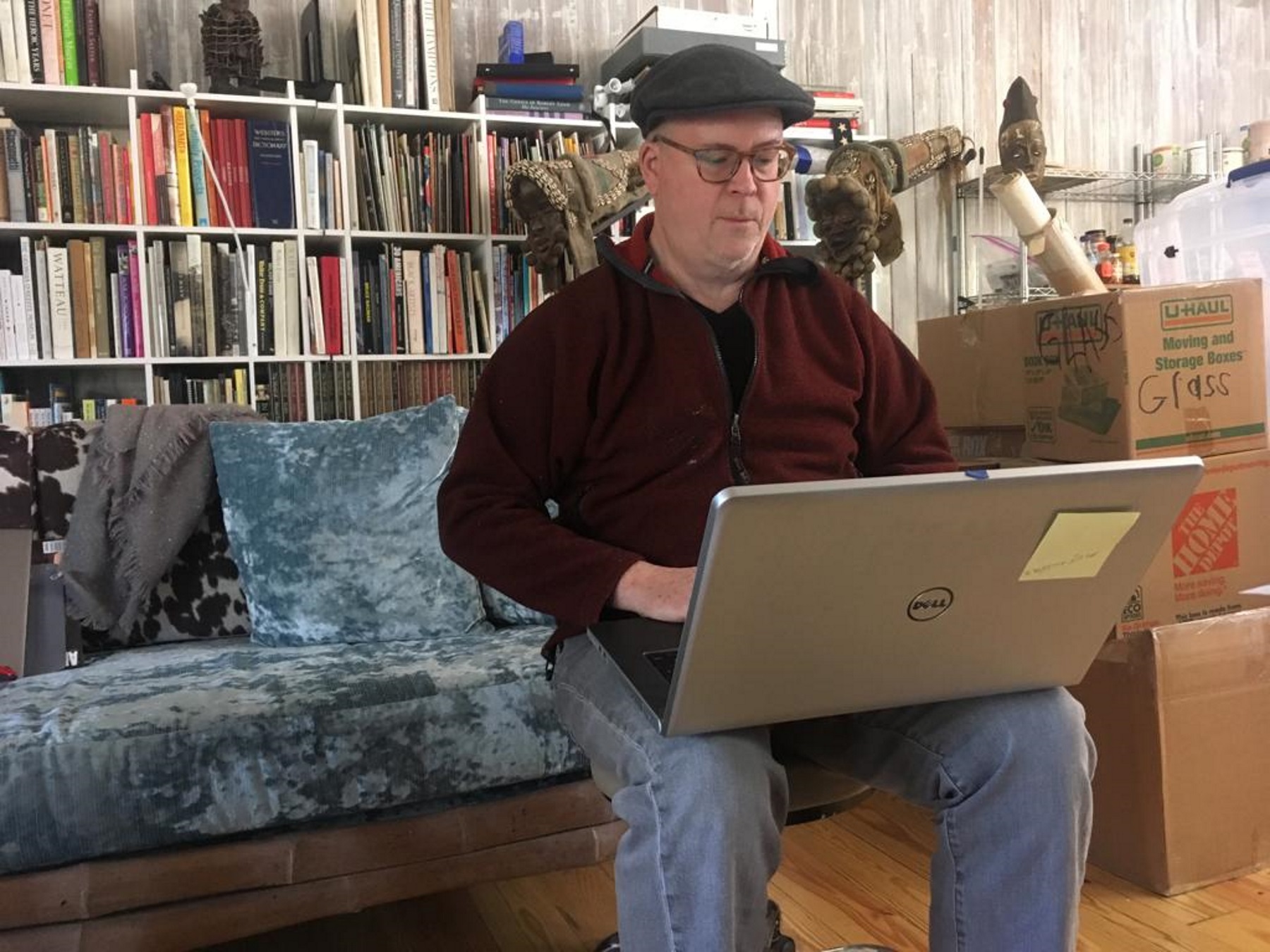

Tom Swanston, a visual artist, has lived in South Fulton County for more than 35 years. When he moved to his new home in the city of Chattahoochee Hills, he said he had trouble getting an internet company to provide him with a reliable internet connection.

Tasnim Shamma / WABE

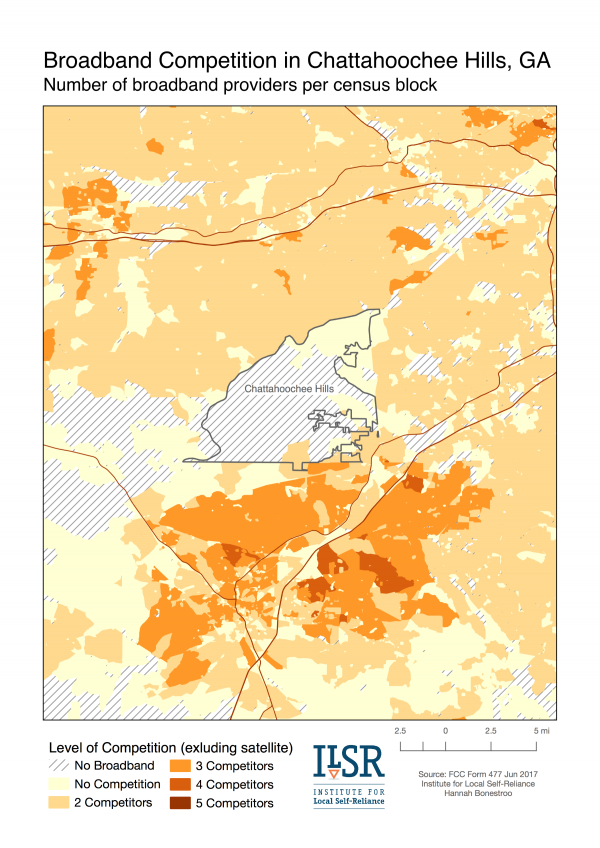

There’s a part of Fulton County, the city of Chattahoochee Hills, where more than 60 percent of residents don’t have access to reliable internet.

State and city leaders are now trying to increase broadband access in rural Georgia.

Just 30 miles away from downtown Atlanta, you’ll find lots of horses, rolling hills and rural, one-lane dirt roads. And a clear example of a place in Georgia where some have internet and others don’t.

Digital Divide

Tim Cailloux is a longtime Chattahoochee Hills-area resident and recently launched the startup Southern Internet.

“This road is literally a digital divide in some respects,” Cailloux said during a drive through the city. “On the right-hand side of the road is Serenbe, where you can order gigabit service from a couple of different providers. On the left-hand side of the road, you can’t even order DSL today.”

Serenbe is an upscale residential and business community where you can get high-speed internet access from Comcast and AT&T. But on the other side of the road where we stop, there are almost no internet options, outside of satellite.

Internet As A Utility

Tom Swanston has a house on the edge of Rico Lake in Chattahoochee Hills. He said he struggled to find an internet service provider willing to install internet at his new home.

“It’s not an option anymore to not have water or power or, in this case, internet service. It’s pretty important,” Swanston said.

Swanston is a visual artist with a studio in Midtown Atlanta. He said he depends on the internet for work.

“Check emails, check my bank balance, check sales, check my website,” Swanston said. “Talk to the studio, see what’s going on before I get going and spend that time driving to work. Not having that ability to check on all of that and keep in touch with it is just stressful. And I’m sure that like I’ll die early because I didn’t have my internet.”

Southern Internet

Swanston has lived in South Fulton for more than 35 years. Last year, he finally got a reliable internet connection at his home through Southern Internet.

A few years ago, Swanston’s wife suffered a spinal cord injury, so he depends on the internet to keep in touch with doctors and sign up for health care. In an area where the nearest supermarket is 45 minutes away, he also buys his groceries online.

“That kind of connectivity out in a rural environment is just amazing,” Swanston said. “Now that we can get Publix, Kroger, Whole Foods, Piggly Wiggly, they all deliver.”

Tim Cailloux, who launched Southern Internet, began setting up antennas on dozens of homes here last year. The signal comes to Swanston’s home from a larger wireless tower a half-mile away.

“Chattahoochee Hills has worked very hard to preserve the rural character and feel of the city. And that means things like trees and not a lot of cellphone towers,” Cailloux said. “As a result, a lot of the comforts of modern life that we know in Atlanta, particularly when it comes to internet access, you just don’t have those available here.”

Christopher Mitchell is with the Institute for Local Self-Reliance based in Minneapolis. His group looks at internet access nationwide. He said the federal government has been slow at ensuring equal access and if cities want to keep their residents, they have to act faster.

“Those who are going to wait for the federal government to get it right in 10 or 15 years will find that the population in their regions has dwindled so significantly that it may not be able to recover just from finally getting broadband,” Mitchell said.

Electric Co-Ops

Mitchell said small internet companies and member-owned electric co-ops are stepping in to fill the gaps, but it’s not enough.

“They’re often doing a far better job than the big companies like AT&T because those companies are locally rooted,” Mitchell said. “They’re motivated not just by profit, but by local pride. The challenge is that building up infrastructure to everyone is just something that I think in some areas will need to be subsidized.”

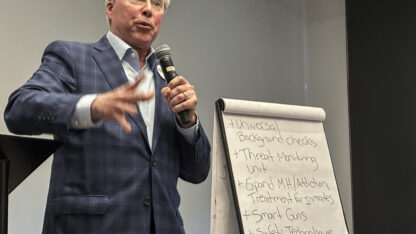

Legislation

Last month, the city of Chattahoochee Hills introduced an ordinance to make it easier for companies to install small cell towers or “5G” wireless. 5G (“Fifth Generation”) is considered 10 times faster than “4G.” State lawmakers are also pushing similar legislation through the Georgia General Assembly.

State Sen. Steve Gooch represents North Georgia — where internet service is spotty. He is sponsoring a bill that would allow electric member co-ops (EMCs) to go beyond providing electricity and offer internet service.

“I believe the EMCs have a different business model,” Gooch said. “They’re not here in a small rural area to make money off their customers. They’re there to provide a service.”

He said currently larger, private internet companies don’t have an incentive to spend millions upgrading the digital infrastructure in rural Georgia. That’s because the companies, which are beholden to stockholders, might not see a return on their investment for decades because of low population density.

Gooch said to increase broadband access in places like Chattahoochee Hills, there will ultimately need to be government subsidies for internet companies in rural Georgia.

“I think it’s something that we’re going to have to put money behind as well,” Gooch said. “The state’s going to have to commit some funding to help incentivize some of those areas to be upgraded. So once we identify the needs and how much money is needed then we can start to look for ways to pay for it.”

State lawmakers have once again said expanding rural broadband access would be a priority during this year’s legislative session, but Gooch said the funding process itself could take at least a couple of years.