Georgia’s Abortion Law Has Doctors Thinking About Their Language

When it comes to language and Georgia’s new abortion law, doctors find themselves trying to serve the needs of their patients while still sticking to the medical science.

Pixabay Images

It’s early morning at Colleen Cherry’s obstetrics and gynecology practice in Atlanta. The office murmurs with activity as providers and staff prep for the day’s patients.

Cherry walks down the hall from her office into a small room, complete with an exam table and ultrasound machine.

“It’s down this way, right in here,” she said.

It’s in rooms like this that Cherry leads patients through their first prenatal visits.

Those start with conversations about last menstrual periods and what pregnancy symptoms patients are having.

“And after that, we do an ultrasound, and then we would get our images on the screen here, and see what we see,” she said.

At around six to eight weeks, the ultrasound can show what’s called a fetal pole that’s just a few millimeters long and the tissue that will eventually form the heart.

Cherry says that tissue should show a little flicker of activity, a heartbeat.

“If you say, ‘Oh, here’s some cardiac activity. Here’s a clump of electrical cells moving.’ People [are] not looking for that. It doesn’t bring the warm fuzzies,” she said.

Cherry says she hasn’t stopped using the term “heartbeat” with her patients, even though it’s been attached to Georgia’s new abortion law by many supporters.

Opponents of the measure are hesitant to use the term, preferring in some cases to call the measure a “forced pregnancy” law.

Fights over access to abortion have long been shaped by language: the current one is no different.

And when it comes to Georgia’s new law, doctors find themselves somewhere in the middle: trying to serve the needs of their patients while still sticking to the medical science.

That’s where Atlanta infertility specialist Heather Hipp finds herself during initial prenatal visits.

“From a more scientific perspective, I acknowledge it’s not a fully grown heart like we picture from anatomy textbooks, but I usually tell them, ‘Look, there’s the heartbeat,’” she said.

Hipp says her patients can work for years to get pregnant. Sometimes even she gets emotional when they’re finally successful.

“I cry probably at least once a day in clinic,” she said. “When you see the beginnings of a baby for someone who has worked so hard to get pregnant, it’s amazing.”

Hipp says she works to establish a good rapport with her patients, and using more colloquial language helps her do that.

But she says she’s much more conscious of using the term “heartbeat” outside her office when speaking with the general public.

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, which has come out in opposition to laws such as Georgia’s, also uses the term in describing the stages of pregnancy.

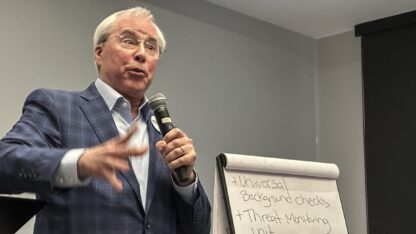

“We try to make sure that everybody uses the language that’s the most appropriate for the situation we’re in, both talking to medical personnel and conveying that information to patients,” said Chad Ray, president of the Georgia Obstetrical and Gynecological Society.

Ray says a good doctor knows her patients’ needs. She can use a term like “heartbeat” in an exam room, even if she opposes its use in legislation.

Georgia’s law is set to take effect Jan. 1 unless a court intervenes.