When Landlords File Evictions In Georgia, Tenants Feel The Effects For Years

Bryson Williams, a renter in Southwest Atlanta, feels like the eviction notice he received at the start of the pandemic has ruined his life. And this isn’t dramatic. When landlords file for eviction in a state like Georgia, a stain appears on tenants’ records that makes it hard to find housing for years.

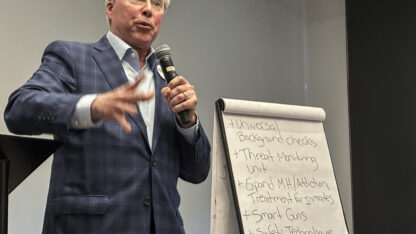

Stephannie Stokes / WABE

Bryson Williams is just getting started as an adult.

He’s 20 years old. The apartment he lives in, right outside the perimeter in southwest Atlanta, is his first in his name.

“And now it’s probably going to be my last for a little bit,” Williams said.

Williams got an eviction notice when the pandemic started. It was the result of a couple things: his effort to get a cheaper unit at his complex fell through right as he was furloughed from his job at the airport.

His case is waiting for a hearing. But what Williams learned shortly after receiving the eviction notice already has him discouraged about his future.

The notice alone, which means the landlord has filed an eviction case against him in courts, is public. That means property owners, and anyone else, can find it when they search Williams’ record.

Williams said the realization devastated him.

“How am I about to live with something on my record hindering me from getting apartments, possibly vehicles, possibly loans?” Williams said. “I felt like my life was ruined.”

He isn’t being dramatic.

There are thousands of eviction cases like Williams’ pending in courts around metro Atlanta. Many are on hold because of an order from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to halt evictions from unpaid rent until the end of the year.

But what’s not well-known is that the eviction filings against those tenants have stained their records in a way that could make it hard to find housing for years.

It doesn’t matter that their cases haven’t gone before a judge.

“You’ve already lost no matter what the court decides,” said Eric Dunn, legal director at the National Housing Law Project. “Most landlords will just categorically deny admission for people that have eviction cases filed against them.”

This is because of how tenant screening often works.

Credit reports can show the outcome of an eviction case, whether a judge agreed with the landlords’ claims. But tenant screening companies typically search more widely to find any public record, including just the start of an eviction case.

Edd Stanley of Keyrenter Atlanta says his property management business, a franchise of a national company, sees this information.

Keyrenter tries to be as thorough as possible. Tenants’ applications go through an internal screening department made up of researchers around the world, most in Latin America, he said.

“We pull their background checks. We do Google searches. Social media profiles we look at,” Stanley said. “We look at everything.”

He said the screening process is one of the most important parts of his job.

He manages a couple dozen properties around metro Atlanta. Stanley said there are plenty of tenants who are glad to move in even if they may not have the resources to cover the rent.

“We are providing a home for these tenants. And once they’re in their home, it’s their home,” he said. “If things don’t work out, it’s not easy to evict.”

Evictions are not in the company’s interest, he said. He wants tenants to remain.

So if there is an eviction filing in a renter’s history, even a resolved one, Stanley said he wants to know about it. That doesn’t mean he’s going to reject the application outright.

“I don’t really stop there. I do like to find out what were the circumstances and I will ask the tenant, “What was going on here?” Stanley said.

But in this respect, he may not be your usual property manager, according to Dunn, the attorney.

Dunn said landlords now can tell screening companies to exclude applicants with any eviction filings in their history and computers automatically filter them out. Human eyes may never see the tenants’ applications.

And then Dunn said those tenants will find they have few options for housing.

“If they want to rent, they’re looking at a second-class rental market,” Dunn said.

That’s a rental market made up of lower quality properties with lower quality living conditions in areas with lower quality schools, he said. They become like second-class tenants.

Williams, the 20-year-old renter, has noticed this. While he said he understands some tenants should face consequences, the burden that comes with eviction filings seems extreme.

“We still have to live and this is why people fail,” Williams said. “I feel like an eviction is like getting a felony in a way.”

The comparison is close. One key difference: Georgia now has a law that allows certain people who have been convicted of a felony to clear that from their record. There is no similar law for eviction records.

Other states and cities do provide tenants with options to clean up their rental backgrounds. California seals eviction records unless courts rule in favor of the landlords. Washington allows renters to apply for restricted access to their eviction history.

But because Williams is a tenant in Georgia, his eviction notice could follow him for up to seven years–the amount of time allowed under the Fair Credit Reporting Act.

He’s working again. He’d like to find a new place that’s more affordable. So far, though, his rental applications have been denied.