The Strategic National Stockpile, which the U.S. has traditionally depended on for emergencies, still lacks critical supplies, nine months into one of the worst public health care crises this country has ever seen, an NPR investigation has learned.

A combination of long-standing budget shortfalls, lack of domestic manufacturing, snags in the global supply chain, and overwhelming demand has meant that the stockpile is short of the gloves, masks, and other supplies needed to weather this winter’s surge in COVID-19 cases.

The Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) is a secret network of warehouses scattered across the country, each one the size of several Walmart Supercenters. It serves as a stop-gap measure during an emergency — a pandemic or say, nuclear, chemical or biological attack.

The SNS has long been viewed as a bridge to help states weather calamity while the government revved up other tools in its arsenal, like the Defense Production Act, to feed additional supplies into the pipeline.

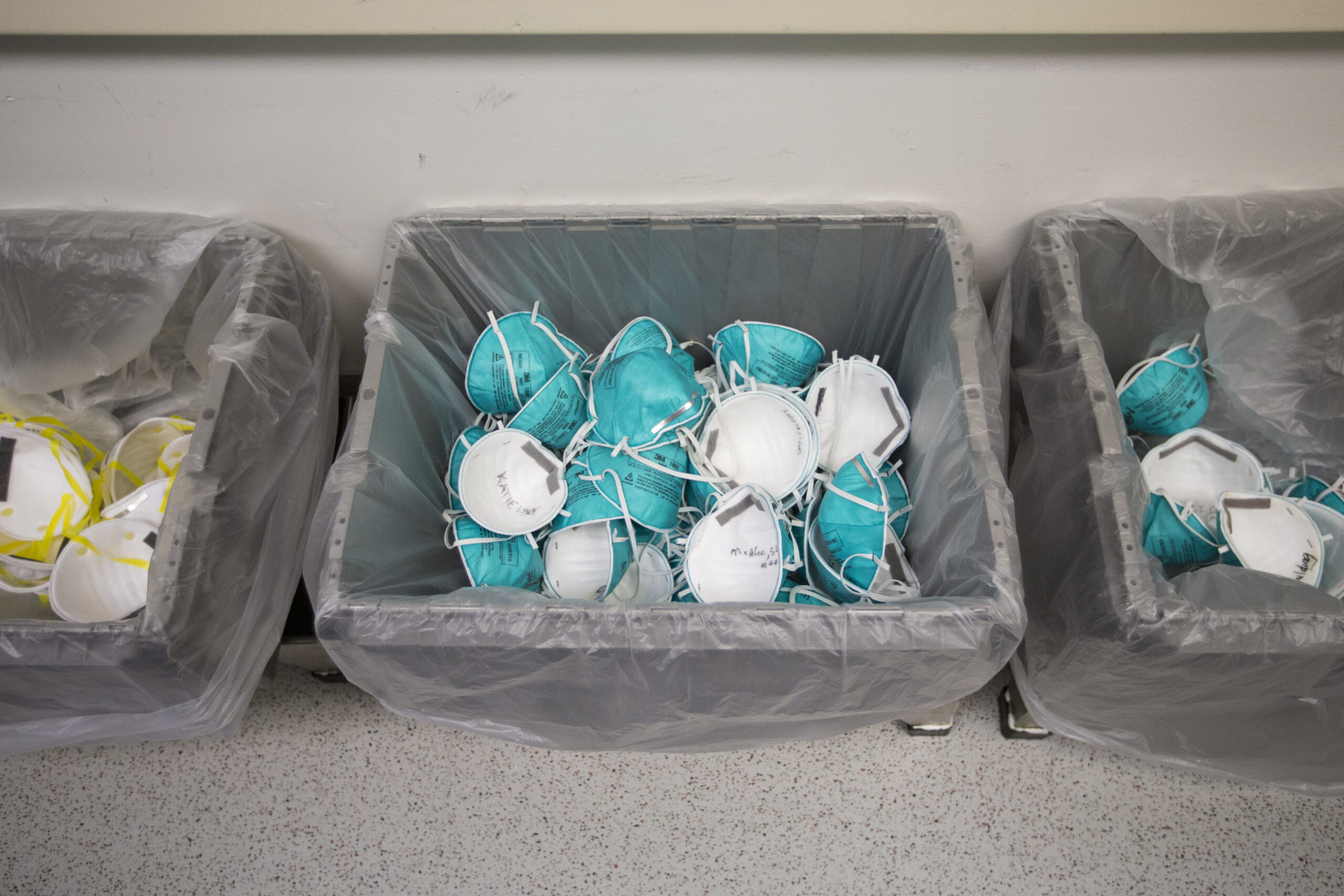

The stockpile constantly receives and sends out supplies. As of late November, its pandemic readiness supplies held some 142 million N95 respirators; 99 million surgical and non-surgical gowns and coveralls; 16 million face shields and 7 million goggles; and 153,000 ventilators, according to a spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services.

While these numbers sound impressive, they fall short of what Trump administration officials had hoped to be able to set aside when the coronavirus laid bare the fragility of the SNS this past spring. The 142 million masks now on the shelves are less than half the 300 million goal that administration officials had hoped to amass by winter. (In January, the stockpile contained only 24 million N95 respirators).

“We’ve achieved much, but not all of it,” says Robert Kadlec, the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response at HHS. Kadlec, who manages the SNS, says they hope to reach their goals by the end of the year.

In a perfect world, Kadlec and other HHS officials had wanted to amass a 90-day supply of critical material by the end of October. Those on the frontlines also believe that officials have vastly underestimated what a 90-day supply should look like, even before the extraordinary surge of cases this winter.

“We need billions more units of PPE to meet the need that we’re seeing across the country” said Dr. Shikha Gupta, director of Get Us PPE, a grassroots organization that provides free PPE to organizations that need it.

Since the organization started eight months ago, Dr. Gupta says it has received 17,000 PPE requests from across the country, which would translate to her organization handing out 22 million units of PPE every week. Most of those requests don’t even come from hospitals anymore, but smaller facilities like nursing homes and shelters. “It’s no longer just medical workers. But now we’re also looking at detention centers and homeless shelters, teachers, and then the mom and pop private practices in rural parts of the country,” says Gupta.

Critical shortages

In 2019, HHS conducted a tabletop exercise called “Crimson Contagion,” a joint operation that tested the government’s response to a large influenza pandemic that, rather prophetically, originated in China. HHS’ Kadlec says the exercise made clear the stockpile was understocked and underfunded.

In November 2019, the SNS’s total budget for this year was set at $745 million — short of the $1 billion that officials managing the stockpile requested.

“And yet we started where we started,” Kadlec said. When the pandemic hit, Kadlec and his team focused not only on getting the necessary supplies, but also re-imagining the whole system. “We really kind of focused on a couple of critical things: Getting better visibility on the supply chain…reducing our vulnerability to foreign suppliers and increasing domestic manufacturing and…the replenishment of our stockpile,” he said.

They called their new vision ‘SNS 2.0: The Next Generation.”

While they’ve had a nearly $9 billion infusion since, there are things they simply cannot fix quickly: for example, the way PPE is sourced. The U.S. doesn’t make a lot of its medical supplies anymore, and relies on an overstretched overseas supply chain that has led to many of the shortages.

For example, the nitrile glove, the industry standard for protection, is made of synthetic rubber and sourced almost exclusively from Asia, which has led to a global shortage. That’s reflected in the stockpile. According to HHS, the stockpile contains 22 million pairs overall, including nitrile gloves – only a fraction of the 4.5 billion it wants to have.

Not making most of this equipment on U.S. soil is one of the core problems. Even if the government manages to store large amounts of PPE, it’s just a band-aid solution.

Former SNS Director Greg Burel says the U.S. needs a whole new supply chain for this critical equipment, though he and other experts agree that it will be painstaking and time-consuming to make that happen. “We need to look at having very competent onshore supply chains, so that we don’t have a disruption as a result of a disease outbreak, say, in another country that limits their manufacturing,” he said. Meaning PPE needs to be manufactured in the United States to avoid the scenario from January when exports out of Wuhan — where the virus first emerged, and also the global manufacturing hub of N95 respirators — essentially stopped because of the pandemic.

‘Like being on eBay’

On March 31, just over a month into the pandemic, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo vented his frustration at the chronic shortage of supplies facing his state: “It’s like being on eBay with 50 other states bidding on a ventilator,” he told reporters at one of his daily press conferences.

He was referring to the unparalleled competition between states trying to secure desperately needed supplies. Ventilators and PPE were all going to the highest bidder because the SNS had little to offer.

The Trump administration made states responsible for their own COVID supplies. Some of the shortfall in the SNS’s inventory might have been filled by the Defense Production Act — which gives the president the authority to order manufacturers to produce a much-needed item, among other powers — but President Trump chose to invoke it sparingly.

That meant that each state had to figure its own way to deal with the shortfalls — all with varying degrees of success. Some states, like California and Oregon, went so far as to lease warehouses to create their own stockpiles. Governors were forced to create their own supply chains.

California worked with “over a dozen different vendors” to secure over 93 million sets of gloves (though not all are nitrile) and 180 million N95 respirators for the state’s use, according to Brian Ferguson, the deputy director of Crisis Communication and Public Affairs for the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services.

That means California now has about 40 million more N95s than the Strategic National Stockpile currently holds. “One of the things California made a priority is…that we had a strategy to have PPE for the long term in our state,” he said.

California is, because of its size, an outlier. Most other states need more help — and the SNS says it has been providing it. “All they have to do is ask the federal government and we will honor that request,” said Brig. Gen. David Sanford, director of the Supply Chain Advisory Group. In an interview with NPR’s Mary Louise Kelly, he said they have not turned down any requests received from the states. “We’ve had 313 since one September and we haven’t said no to any.”

But there is a difference between turning down a request and meeting it fully. Robert Handfield, a professor at North Carolina State University and a supply chain expert, said that state officials he has interviewed from across the country had received some of what they requested from the stockpile but far less than they were promised. “I think several of the states are having a tough time, particularly the smaller states like Maine, New Mexico, and Nebraska,” he said.

HHS’ Kadlec says some of this is simply a question of supply and demand where the supply simply cannot keep up right now. “What we try to tell them is that there is no silver bullet to magically have another billion masks here overnight, that’s just not going to happen.”

Yet where the nation finds itself heading as winter approaches is dispiriting to some. Dr. Gupta of Get Us PPE said it’s unacceptable that the U.S. is still facing shortages of critical equipment.

“We’ve had so many opportunities to pay respects to our health care workers and frontline workers, not by clapping for them at 7 pm or sending them free pizza, but by giving them the protective equipment that they need,” she said. “We need to do a better job of getting people what they need to walk into work, protected and confident that they can take care of themselves as well as the people around them.” Anything less, she said, is “not what they signed up for and that’s not the American way.”

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))