At Amphibian Class, Atlantans Learn To Recognize Their Slimy Neighbors

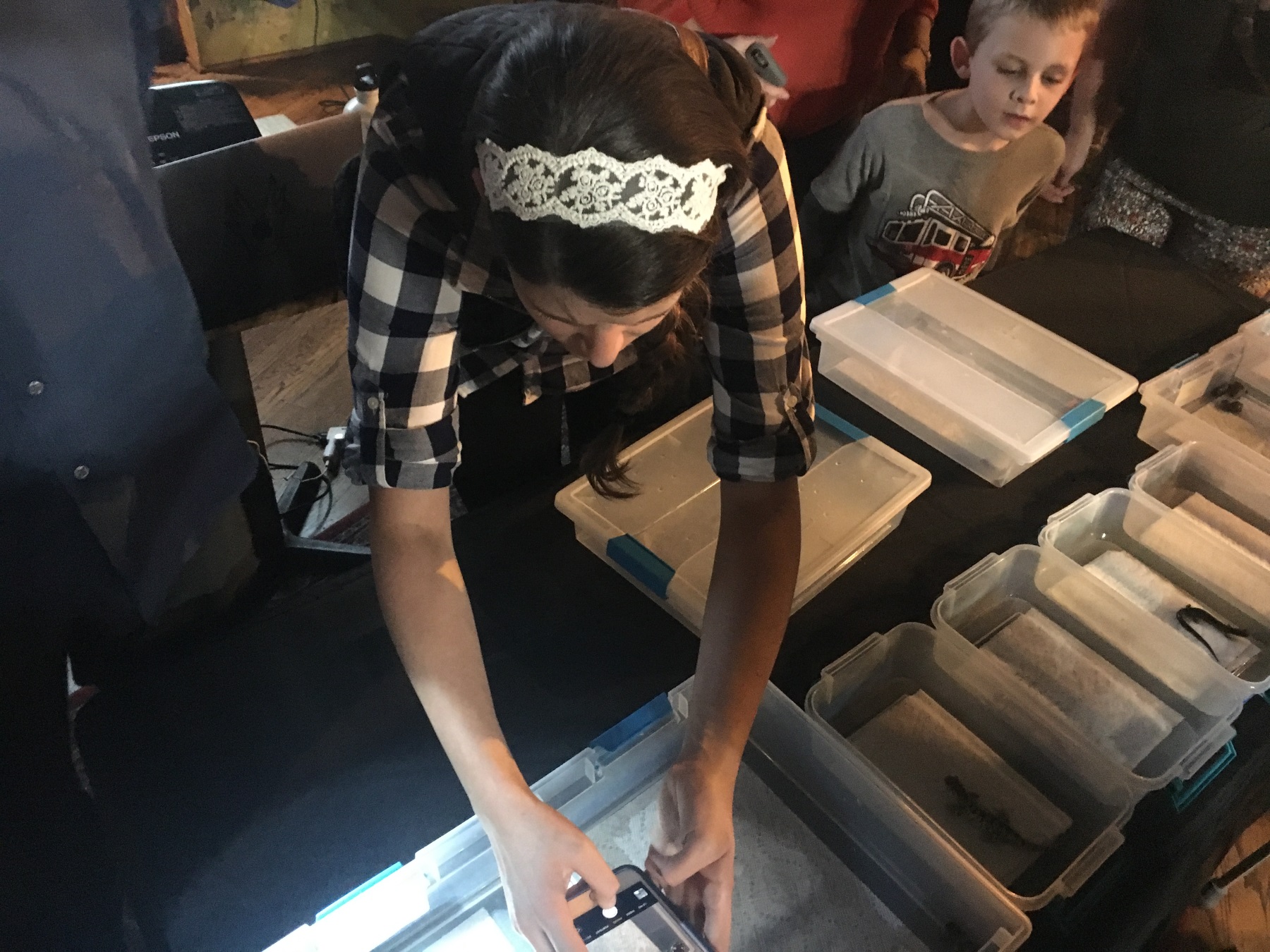

Eight-year-old Liam Namer looks at salamanders at an Amphibian Foundation class at Kavarna coffee shop in Decatur.

Molly Samuel / WABE

Atlanta is a good place to find amphibians. Nearly 30 species live in the metro area, from slimy salamanders – that’s the name of the animal, not a mean description – to bullfrogs.

They’re in backyard creeks and ephemeral wetlands — basically, temporary puddles and ponds.

“Some of them haven’t been seen in a while, but they’re beautiful and amazing,” said Mark Mandica, director of the Atlanta-based Amphibian Foundation.

The Amphibian Foundation tracks Atlanta’s frogs and salamanders through its Metro Atlanta Amphibian Monitoring Program. (Toads are kinds of frogs, so they count, too.) The goal is to figure out where they live and where they may need some help, for instance, with habitat restoration.

The Amphibian Foundation also teaches Atlantans about their local frogs and salamanders in occasional free classes.

“I like people to learn the frog calls, and then they know what they’re hearing at night,” said Mandica. “It’s exciting for some nerds like me.”

About 50 people showed up to a recent class in a Decatur coffee shop, including 5 1/2-year-old Ruby, who came with some friends and her dad, and, having once encountered a salamander in her shoe, had a question: “Why are salamanders so slimy?”

Short answer: Because they breathe through their skin, and it needs to stay moist.

Once people are good enough at identifying Atlanta’s frogs and salamanders they can help the Amphibian Foundation identify where the animals live.

“Some species we’ve only found in one or two sites inside the Perimeter, so some of them aren’t doing very well,” Mandica said. “Most of them use ephemeral wetlands. So it’s hard to even imagine where these ephemeral wetlands – temporary pools, I like to call them puddles – even exist. Because we’ve only found a handful of them left.”

Amphibians are important, Mandica said. For one, frogs eat mosquitoes.

Around the world, amphibians are in trouble. A fungus has driven some to extinction. Others are at risk from habitat loss, water pollution and climate change.

“We have to pay attention to what [amphibians] are telling us, for the amphibians’ sake, but also for our sake,” Mandica said. “We’re silly to think we’re not somehow connected to all these reasons the amphibians are disappearing.”