As the nation gears up for a massive vaccination effort, the Trump administration is doubling down on a novel, unproven injection device by providing more than half a billion dollars in government financing for something that is still awaiting Food and Drug Administration approval.

Later today, the U.S. International Development Finance Corp, or DFC, is expected to announce that it has extended a $590 million loan to ApiJect Systems America, NPR has learned. The Connecticut company makes a disposable injection device that it says can be mass produced to deliver vaccines and medications around the world.

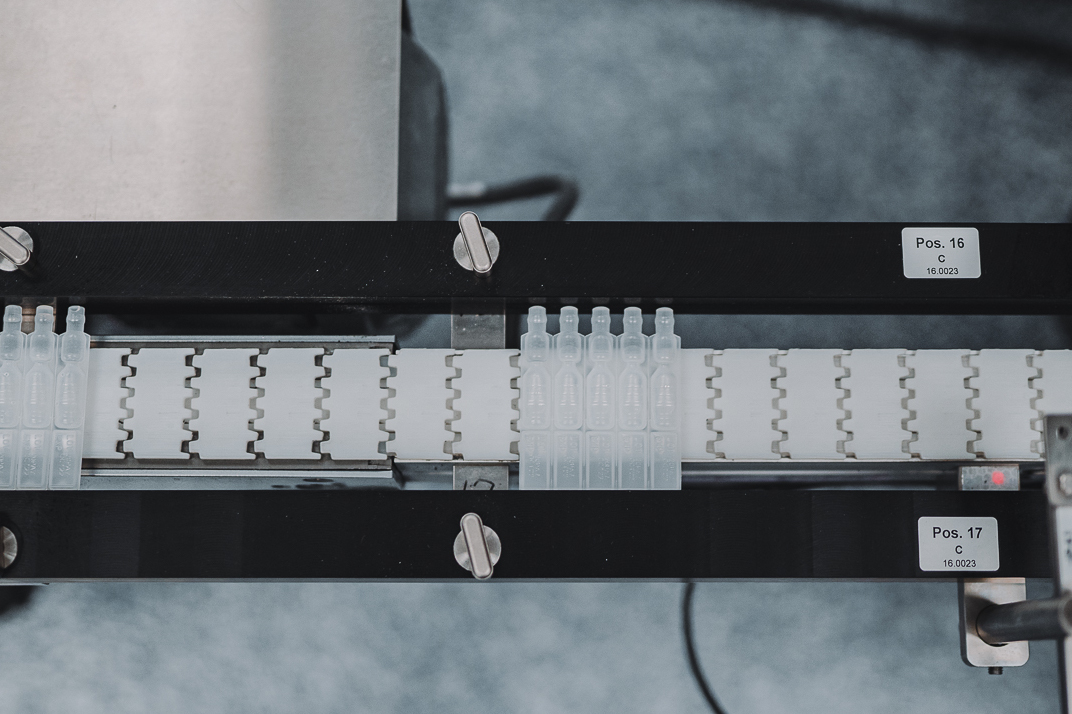

The single-use, self-contained devices are designed to be an alternative to traditional vials and syringes. “This is going to be, we believe, the next generation of safe injections worldwide,” ApiJect Systems Corp. Executive Chairman Jay Walker told NPR.

The hefty investment in an unproven device is also part of the administration’s attempt to hedge its bets against any potential for equipment shortages and supply-chain glitches as it starts to roll out COVID vaccines. Unforeseen shortages of swabs and chemical reagents plagued early efforts to distribute coronavirus tests and it took months to catch up.

“I think it is sensible to have backups to glass vials,” said Nicole Lurie, a strategic advisor at the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations who served as the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response at the Department of Health and Human Services. She says the fact that the administration has placed such a large bet on a technology that hasn’t cleared FDA hurdles gives her some pause.

“The challenge that I see is that it is a completely untested technology and it is not clear to me what kinds of conversations ApiJect has had with the FDA or any other regulators,” she said. “What testing has been done to ensure that the materials inside the containers don’t interact with the compounds of various vaccines? They probably need to be tested for each vaccine and especially each vaccine platform.”

The Pfizer vaccine for example, needs to be kept at arctic temperatures. ApiJect says that its devices can handle that, but the FDA hasn’t certified that they can. The new loan is on top of some $150 million in previous contracts ApiJect landed with both the Defense Department and Department of Health and Human Services — all for the single-dose plastic injection syrette, as they call it, a little bigger than your thumb.

The FDA has yet to approve its use, but the Trump administration clearly sees ApiJect as a component in the next phase of the race for a vaccine. As companies like Pfizer and Moderna prepare to apply to the FDA for Emergency Use Authorization of their COVID-19 vaccines, they’ll soon need the means of packaging, distributing and injecting perhaps billions of doses of those vaccines.

There is concern among public health and Trump administration officials that this so-called “Fill-Finish” part of the vaccine manufacturing process — producing glass vials, filling them with the vaccine, securing syringes, and then distributing them across the country — will create enormous bottlenecks and prevent the vaccine from reaching Americans in a timely way.

That’s what happened during the first phase of the pandemic when Americans rushed to doctors offices and medical centers to get COVID-19 tests only to be turned away because of a shortage of reagent chemicals, testing kits, and nose swabs. State laboratories that were also facing shortages began competing on the open marketplace for pipettes and lab materials they needed to process the tests.

Two major purveyors of medical vials are Corning Incorporated in New York and Schott Pharmaceutical Systems in Germany, and the worry is that any unforeseen production problems at either of their factories could have a disastrous effect on the administration’s vaccination efforts. As it is, built into the glass vial production estimates is a 20 percent overrun, to account for breakage. If something goes wrong — say there is a shortage of vials — that could derail the whole enterprise.

Walker says, of ApiJect: “We are the back-up plan.”

Back-up plans

The DFC financing is meant to help ApiJect build a million square foot campus in North Carolina for a speedier fill-finish operation. It will take pharmaceutical-grade plastic resin, pour it into a mold and then move it to a sterile filling space where the drug or the vaccine will be inserted before it is sealed.

ApiJect says when the GigaFactory, as they call it, is fully operational it will produce as many as 3 billion single-dose injectors a year. They expect the project will create some 650 jobs in Research Triangle Park, N.C.

ApiJect has to raise $200 million on its own to qualify for the federal funds.

The company first came to the attention of the administration by chance. Walker, one of the founders of the travel booking website Priceline found himself sitting next to now-Assistant Secretary for Health Adm. Brett Giroir at a medical conference several years ago and he happened to have an ApiJect device in his pocket.

Giroir thought it might be a solution that could change the national stockpile. Instead of warehousing material, the thought was, they would just have the production capacity to produce something fast. To test the theory, in December 2019, ApiJect got a small $13 million contract from HHS to build out their capacity. A few months later, COVID happened.

The $590 million ApiJect loan from DFC is the first high visibility loan the agency has awarded since its ill-fated decision to give Eastman Kodak in Rochester, N.Y., a $765 million loan to refashion itself into a pharmaceutical company to produce generic drugs. That deal is now on hold as various agencies and congressional committees investigate allegations of insider trading and concerns about how the loan was awarded in the first place.

The ApiJect loan was made possible by an executive order President Trump signed in May that cleared the way for the DFC — which had previously been called Overseas Private Investment Corp. — to make loans to ramp up domestic production to address the coronavirus. The DFC is run by Adam Boehler, a healthcare professional, White House senior advisor and former roommate of Trump son-in-law Jared Kushner. ApiJect said company officials never dealt with Boehler directly.

ApiJect’s technology has been used for years in the liquid pharmaceutical market, typically including solutions for ophthalmic, respiratory therapy and injectable drug products.

It hasn’t been used in precisely this way before, however, and it is unclear whether it will get FDA approval to do what it wants to do. That means it is unclear whether the Trump administration’s gamble on the company will pay off.

ApiJect Chairman Walker said the FDA has been working with the company and “we’re through all the hard parts.”

A FDA spokesperson said federal rules preclude the administration from talking about products that have not been approved.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))