How Atlanta Became The Capital Of Income Inequality

The city of Atlanta regularly shows up at the top of lists on income inequality. But there may be more to the story than the ranking.

Grace Walker / WABE

This story was produced in collaboration with the Ravitch Fiscal Reporting Program at the Newmark School of Journalism at the City University of New York. The program funded projects in New York, Seattle, Atlanta and cities in Texas to understand the role that state and local policies play in reducing or exacerbating income inequality.

Atlanta is the capital of income inequality.

So says the Brookings Institution, which has ranked the city’s wealth disparity as the worst in the United States for three out of the last five years.

The latest analysis found those in the city of Atlanta’s top income bracket made nearly 20 times more than those at the bottom. And that’s not the only source for the city’s title. This year, Bloomberg also put Atlanta at the top of its list of wealth divides in the U.S. The career site Zippia did the same.

Headlines highlighting the city’s exceptional inequality are almost an annual tradition.

The ranking can seem intuitive to anyone who’s driven north to south on the downtown connector and seen high rise developments fade into vacant warehouses.

But it may hide some important context, which could explain how the city ended up so unequal.

A City Unlike The Region

“It probably doesn’t tell the whole story,” David Sjoquist, a professor in Georgia State University’s Fiscal Research Center, said.

Sjoquist said to get a fuller understanding of wealth inequality in Atlanta, you should also look at incomes beyond the city in the metropolitan area.

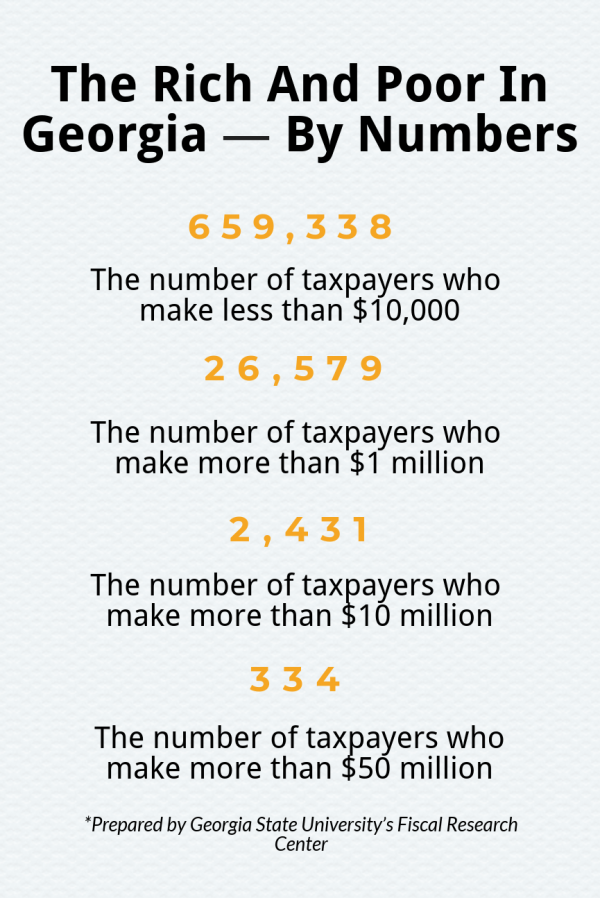

With that broader view, his team at Georgia State found the highest income earners in the region make nine times more than the lowest income earners.

That might still sound like a lot, but it’s half the divide in wealth that you see in the city.

And it significantly changes the overall ranking. While Atlanta may be the leader of inequality, the metro area tumbles to 19th place.

So why does the region look more equal — or, at least, less unequal–than the city?

“It’s partly because Atlanta is so small that it isn’t really representative of the metropolitan area,” Sjoquist said.

Less than ten percent of the people in the region live within Atlanta’s limits, making it one of the least populous major cities compared to its surrounding metro area.

Looking at land use, looking at the political dynamics, all these played a major role in not only racial segregation but also income segregation.

Robert Bullard, a professor of planning at Texas Southern University

But as Sjoquist said, Atlanta’s size only explains part of the difference between the city and the metro area. The type of population the city is missing because of its limited borders is also key.

“We don’t have a good middle income population and we’ve not had that for sometime,” Sjoquist said.

In fact, he found Atlanta had one of the smallest middle classes among the 50 U.S. cities studied in the Brookings report.

And this really gets to the core of the discrepancy between the city and metro area.

That’s because, unlike the city, the region does have a middle class population. Those middle class people are just outside Atlanta limits, in the suburbs.

The Flight Of The Middle Class

The story of how Atlanta became this concentrated center of inequality in a more moderate income region has its roots in racism.

Sjoquist said you can pick up the narrative in the 1960s when Atlanta integrated its public schools and the Fair Housing Act banned discriminatory housing policies.

Rather than face the possibility of black families entering their schools and neighborhoods, many white families simply decided to leave.

More than 150,000 white people — one third of the city’s population — abandoned Atlanta in the decades that followed.

And as they resettled in the new suburbs in Gwinnett, DeKalb, Forsyth and Clayton Counties, they took the middle class with them.

Sjoquist said the black families that replaced white households in these vacated neighborhoods often had lower incomes.

They also had access to fewer opportunities to grow their wealth.

Robert Bullard, now a professor of planning at Texas Southern University, wrote about this period that laid the groundwork for Atlanta’s wealth divide in his book, “Sprawl City.”

He said the region’s economic growth strategically left out the city’s low income black residents.

“Most of the jobs that were created in the 70s were located in areas outside of MARTA access,” Bullard said.

In general, after the new white suburbs rejected the transit system, anyone who relied on MARTA was constrained mainly to Atlanta city limits.

Bullard said the suburbs took steps to keep it that way by, for example, opposing apartment developments.

“Looking at land use, looking at the political dynamics, all these played a major role in not only racial segregation but also income segregation,” Bullard said.

And like the city’s racial segregation, that income segregation persisted — even as the center of Atlanta saw a surge in new investment with the 1996 Olympics.

Mike Dobbins served as Atlanta’s planning commissioner around that time. He said while the period did bring change, it wasn’t enough.

“I think some areas have gotten better,” Dobbins said. “Maybe more areas have gotten better than worse but we’re still stuck.”

Georgia’s Influence

Some argue that it’s also worth looking to the state level for answers about Atlanta’s inequality ranking.

Wesley Tharpe of the Georgia Budget And Policy Institute, a left leaning think tank, said state policies, even if not totally responsible for the city’s divide, could help narrow it.

“There are a lot of things available to state policymakers, a lot of levers they can pull, that can help families and communities come a little bit closer together economically,” he said.

One example might be raising the minimum wage, Tharpe said. Georgia’s has been stuck at five dollars for more than a decade. It’s still low enough that the federal minimum — $7.25 — applies.

State legislators have not supported that or other approaches, like paid family leave. And worse in Tharpe’s eyes, they’ve passed laws prohibiting cities from trying those approaches on their own.

“It takes away the ability of whether it’s Atlanta or Savannah or you know places like Valdosta to enact policies that may be a little bit more tailored to their own local needs,” Tharpe said.

But Rep. Terry England, a Republican from Auburn at the fringe of the metro area, believes Georgia has employed better tools to address poverty.

He said that it’s a problem that’s affecting not just Atlanta, but also rural areas.

In the eight years that England has worked on Georgia’s budget, he said the state’s created a program that covers college tuition for training in certain industries, like nursing and welding.

Most of all, England said the Georgia Capitol has created a business friendly environment throughout the state. He sees that as the best strategy lawmakers could follow.

“When businesses come here from other states, other countries,” England said, “that creates more jobs creates more opportunity for individuals that live here.”

And as a state legislator, England said that is what he focuses on.

“Not so much income inequality but more of an opportunity for folks to be able to do better than maybe they’re doing right now,” England said.

Less Inequality, Same Problem?

Sjoquist, the Georgia State professor, said Atlanta’s income inequality ranking isn’t a problem in itself.

After all, the city could eliminate the negative rating by moving low income residents out of the city.

To some extent, Sjoquist said Atlanta is already seeing that take place with new, wealthier people relocating to once poorer neighborhoods.

“Look at what’s happening on the BeltLine,” he said. “That’s going to continue, and that’s going to eventually result in a smaller low-income population in the city.”

But if that low income population is shifted to the suburbs, Sjoquist said, the inequality will be shifted there too.

A real solution actually would need to help those in lower tax brackets get to a better place.

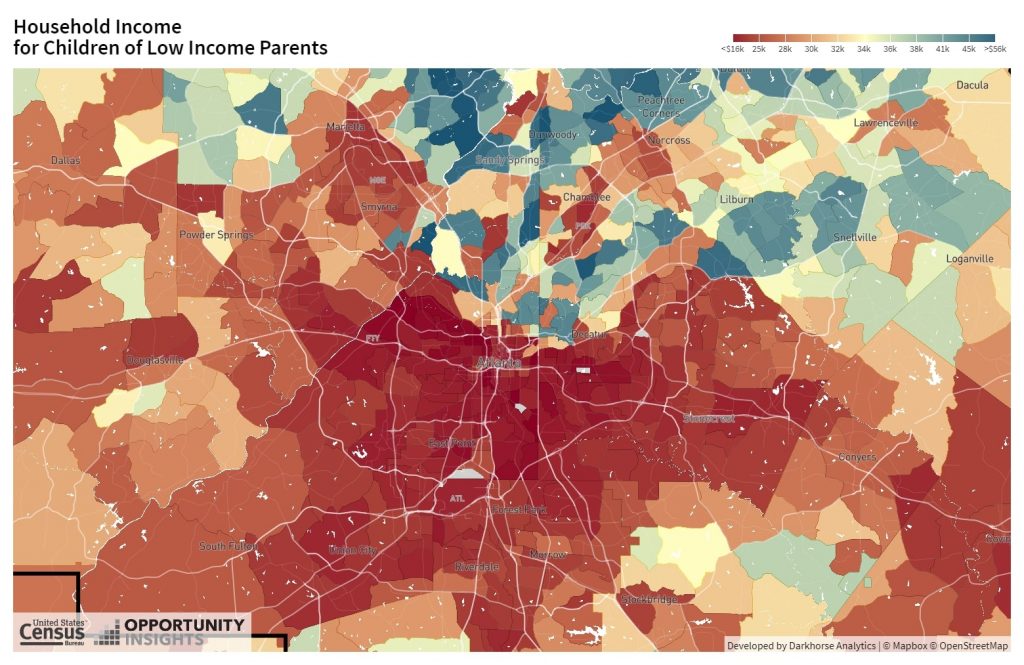

That is not an area where metro Atlanta has a strong record. Research from Harvard University found children born poor in the region face some of the worst odds in the country for growing up to be anything else.

On a recent visit to Atlanta, the leading economist behind that work, Raj Chetty, pointed to the area’s high segregation and concentrated poverty as factors that might be to blame.

But he did say there was something that surprised him about metro Atlanta: its high job growth. The region saw some of the greatest employment gains among U.S. metro areas in the two decades after 1990.

That means the city is creating economic opportunities, he said, just not for its current residents.

“It seems like there is an opportunity to fix that,” Chetty said.