In Atlanta Mayoral Election, Does Race Matter?

In Atlanta, some argue that even if race influences certain issues, it won’t decide the election.

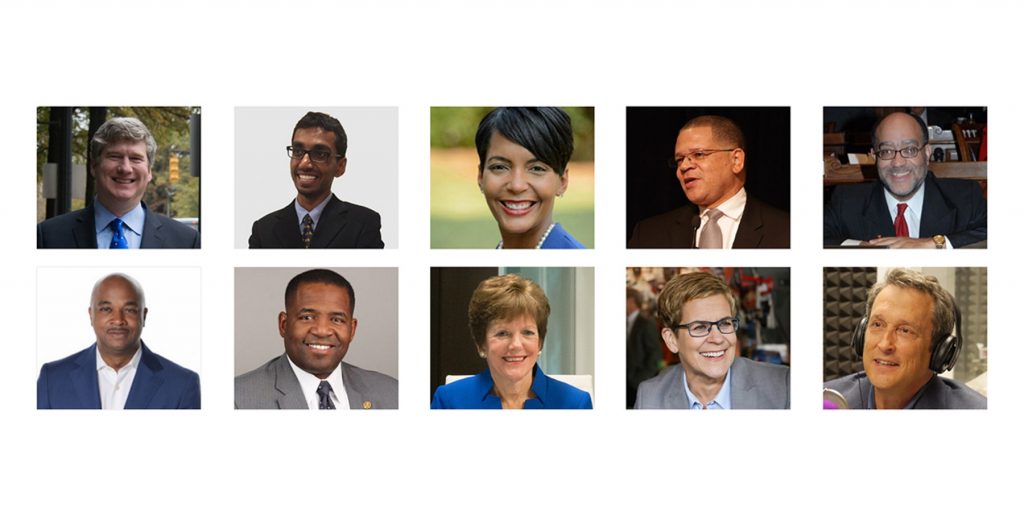

David Goldman / Associated Press file

This mayoral election, Atlanta voters are choosing from one of the most diverse pools of candidates in recent history — diverse in that so many candidates are white.

Black mayors have led the city for more than 40 years. And the possibility of that changing raises a question: Does race matter?

If you ask voters strictly about their top issues, race doesn’t typically come up.

Jack Brandon showed up to a mayoral forum in Buckhead largely about traffic. He said he wants to see the next mayor address that.

“My road goes right out onto Peachtree Road,” Brandon said. “So it’s a huge issue for me. Unless we have some sort of public transit, subway, something, the roads are only going to get worse.”

The following week, at a debate about housing in the Sweet Auburn Historic District, Melinda Weekes-Laidlow shared other concerns.

“I care about the income inequality in the city. I care about the blight on the westside and southside. I care about homeownership and affordability,” Weekes-Laidlow said.

These issues have dominated much of the conversation this election — congestion on the northside of Atlanta and disinvestment on the southside. But can they be separated from race?

“Let’s be honest. Race is always there,” said William Boone, a professor at Clark Atlanta University.

Boone studies city politics and his answer to that question is “No,” despite the image Atlanta may market.

“Atlanta has tried to portray itself as a city that demonstrates how the races can operate harmoniously,” Boone said. “But at the same time, race has been a very prominent component of the city’s history.”

He said the result is obvious: the southside, which has struggled to get development, is mostly black. The northside where development is almost overwhelming? It’s predominantly white.

And when issues break down by race, it’s easy to see how voters’ choices can fall along racial lines, too.

“If they feel traffic is their biggest issue, they will want candidates who understand the need to solve the congestion issue,” said former Mayor Sam Massell. “I think it’s based on what you feel really represents your interests.”

Massell holds the title of Atlanta’s last white mayor. His campaign for re-election in 1973 was defeated by Maynard Jackson, the city’s first black mayor.

Massell thinks this year’s candidates are whiter because of attention to the city’s changing demographics — that Atlanta has become whiter. He’s accepted race is a factor in politics.

“People try to select candidates who will best understand their needs and their problems,” Massell said. “That’s normal, I think. Whether you win or lose, you have to face up to that.”

But some argue that even if race influences certain issues, it won’t decide the election.

The Rev. Raphael Warnock, who leads Ebenezer Baptist Church, for example, said no candidate should take votes in the black community for granted.

“There’s really too much at stake. There are a lot of people who are doing well. There are way too many people who have been stuck at the bottom of the bottom,” Warnock said.

And they’ve been stuck there no matter who their mayor has been.

Warnock said the election of the late Mayor Jackson was important. But he expects voters this year to consider each candidate.

“I think ordinary citizens are open and are wondering who is going to help move Atlanta forward not just for some Atlantans, but for all Atlantans,” he said.

That’s something candidates have stressed over and over again: they will be mayors for all of Atlanta, all communities. Race goes unacknowledged.

Emory University political science professor Michael Leo Owens said he thinks that’s the hope for most of the electorate, but he has doubts that candidates can be “mayors for all” once in office.

“I don’t think that mayors can equally distribute all the good things of governance to all parts of the city,” Owens said. “And so that, of course, means you’ll have to have a mayor who’s willing to make very tough choices.”

And those choices may be between one neighborhood’s need for relief from traffic and another neighborhood’s need for relief from blight.