Atlanta, Southern Company Make Climate Promises. The Challenge Is Making Them Happen

In Atlanta, the city is working on a program to install solar panels on a dozen municipal buildings and on increasing energy efficiency. That’s just part of Atlanta’s ambitious climate change goal. Meanwhile, Atlanta-based Southern Company announced its own emissions goal. Making announcements is one thing, but implementing these goals is another. For Atlanta, it can be complicated.

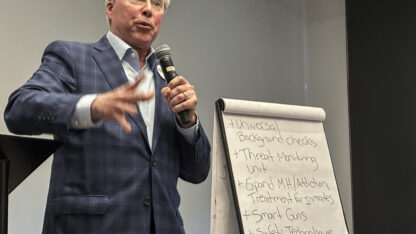

Jaime Henry-White / Associated Press file

Earlier this year, Atlanta adopted an ambitious climate change goal: To have all homes, businesses and city operations rely largely on renewable energy by 2035.

Meanwhile, Atlanta-based Southern Company announced its own emissions goal: To achieve “low- to no-carbon” by 2050.

Both are part of a trend of companies and local governments making climate change announcements and promises. But making announcements like these is one thing. Implementing them is another.

More than 100 local governments have made pledges, but following through depends on local regulations and politics. A handful of cities and towns have already completely switched to renewable energy sources, according to the Sierra Club.

In Atlanta, it’s complicated.

Here in Atlanta, utility customers – including the city – don’t choose where their energy comes from. Georgia Power, a subsidiary of Southern Company, makes that decision.

And Georgia Power isn’t considering the city’s – or its own parent company’s – carbon goals as it develops its long-range plans.

Carbon ‘Not A Driver’ In Decisions

Every three years, Georgia Power puts together a long-range energy plan, called the Integrated Resource Plan. The plan is going through the approval process now at the Public Service Commission, with a first round of hearings that happened in April and a second round this week.

In the April hearings, Atlanta’s energy plans came up a handful of times, and Georgia Power was frank about not factoring in either the city’s goal or Southern Company’s in the IRP.

“Carbon in and of itself is not a driver in the decisions we’ve made here,” said Jeffrey Grubb, director of resource planning at Georgia Power.

Georgia Power’s carbon dioxide emissions have decreased by more than half since 2007, largely because the company has switched to natural gas as it’s out-competed coal on cost. The company has added solar power the past several years. Now, Georgia Power is proposing to close a coal-fired power plant, close a coal unit at another plant and add additional solar power.

Still, economics trumps emissions reductions.

During the hearings, Kurt Ebersbach, senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center, asked a hypothetical question: If the economics changed, and coal became cheaper than natural gas, would Georgia Power use more coal, thereby raising emissions? The answer was yes.

Georgia Power says it makes its decisions in the interests of its customers, prioritizing cost, safety and reliability. Not emissions reductions.

And that’s what the Public Service Commission is looking for.

“Our goal is not exclusively clean energy,” said commissioner Tim Echols. “We have as part of our goal to have a reliable grid, an economic grid, a safe grid and a clean grid. And so we’re not going to move forward with clean unless it’s economic.”

Southern Company’s Goals

Georgia Power’s priorities would seem to be out of line with Southern Company’s.

The board of the larger parent company recently linked CEO Tom Fanning’s pay with emissions reductions.

“It shows, I think, the company is thinking about [carbon reductions],” said Paul Patterson, an analyst who covers the electric power sector at Glenrock Associates. “The board of directors is signaling that climate change is a component that they’re focused on.”

The board of directors might be focused on it, but not so much that the parent company will weigh in on its subsidiary’s long-range planning, at least not publicly.

In a document filed with the Public Service Commission, Georgia Power wrote that Southern’s goals did not change its planning process.

WABE asked Southern Company to comment on its subsidiary not implementing more carbon-reduction efforts but was referred back to Georgia Power.

Atlanta’s Goals

At the long-range energy planning hearings this week, environmental and solar industry groups will argue that Georgia Power could be adding more renewables to its portfolio. And in past decisions, the Public Service Commission has directed Georgia Power to add more solar than it had initially proposed.

As it stands now, Georgia Power’s Integrated Resource Plan would not do much to advance Atlanta’s goals, which call for moving away from coal, natural gas and nuclear in 16 years, using some combination of renewable energy, energy efficiency and renewable energy credits. In 2017, the City Council passed a resolution saying it wanted to achieve similar goals. Earlier this year, it adopted a document that outlines ways to do it.

Echols said it’s not the job of the PSC or Georgia Power to make Atlanta’s goal happen, just because the city wants it to. But, he said, the commission could help.

“There’s a chance that our commission could be sympathetic. We do have the ability to compel Georgia Power to do things,” Echols said.

But Atlanta hasn’t shown up to the hearings on the IRP.

“To my knowledge, this commission has not been noticed in any form,” PSC chairman Bubba McDonald said of Atlanta’s plans last month.

No one from the city came to the public comment session at the beginning of the April meetings, and the city didn’t apply to intervene in the proceedings, which would have allowed it to question experts and present its own evidence and witnesses. City Hall is across the street from the PSC.

“Just because we weren’t there doesn’t mean we weren’t monitoring and engaging in the process generally,” said Amol Naik, director of resilience for the city of Atlanta.

Naik and Echols have had meetings, and since last month’s hearings and WABE’s inquiries, the city has scheduled meetings with other PSC commissioners. And the city plans to submit a letter for public comment in the IRP hearings this week. Naik said he’s had productive conversations with Georgia Power.

“We really appreciate their partnership, and I think we’ll be able to work with them just fine,” he said.

A spokesman for Georgia Power said the company is committed to partnering with its customers, including Atlanta, on renewable energy.

But the city hasn’t been in the room where the decisions are being hashed out.

“They should be there,” said Jairo Garcia, who teaches at Georgia Tech and used to work for the city of Atlanta on climate policy.

He said it’s urgent to take action on climate change – as soon as possible – and to do that, the city needs to engage with the IRP.

“If we miss this IRP, we have to wait three years. Basically, we are waiting for the next mayor to do something about it?” he said. “It’s just very disturbing.”

Garcia said he thinks Atlanta could have an effect on Georgia Power’s plan, but he said it’s going to require the city to stand up and take leadership on it.

Local Tools Versus Global Tools

The piecemeal approach, of cities and companies saying they want to reduce emissions, and then – sometimes – struggling to accomplish their goals, is not the most efficient way to tackle the problem, said Mindy Goldstein, a professor at Emory Law School and director of the Turner Environmental Law Clinic.

“This problem is really one that’s global in scale,” she said. “You’re going to, in a perfect world, have global solutions. That’s just not where we are today.”

A national solution would work better, too, she said.

“In the absence of federal leadership, what you’ve started to see is different entities step in, and that can be exciting,” she said, as they come up with different solutions, tailored to local contexts.

“They may not look like a complete solution,” she said. “That’s because they don’t have all the tools that they need to get all the way there, but they have a lot to get a lot of the way there.”

In Atlanta’s case, the city is working on a program to install solar panels on a dozen municipal buildings and on increasing energy efficiency.

And in the Sierra Club’s view, Atlanta has done good work on its clean energy goal, even if it’s not at the IRP hearings. Kass Rohrbach, deputy director of the environmental group’s Ready for 100 campaign, said the city’s work developing a plan and getting community input are big steps.

And, she said, efforts like this – basically rethinking how a city gets its energy – take time.

“We see the commitments as really the first step,” she said. “This is a long-term campaign and a long-term fight that we, as the Sierra Club, are committed to pursuing with these communities.”

The Sierra Club is working with Atlanta on the city’s climate goal. And it’s also involved in the Georgia Power hearings. Ted Terry, director of the Georgia chapter of the Sierra Club, said the organization is representing the city’s interests at those hearings, even if the city itself is not there.

There are other cities around Georgia working on similar goals, and Atlanta could lead them.

Terry, who’s also the mayor of Clarkston, is optimistic about that potential. He said even though Atlanta isn’t at the hearings this year, maybe next time, in 2022, it will be. And other smaller cities might join it at the table with Georgia Power and the Public Service Commission.

“I think that Atlanta has one of the most comprehensive transition plans in the Southeast, if not the entire country,” Terry said.

The challenge now is making it happen.

WABE reporter Emma Hurt contributed to this article.