A Family’s Search For Affordable Housing In Atlanta

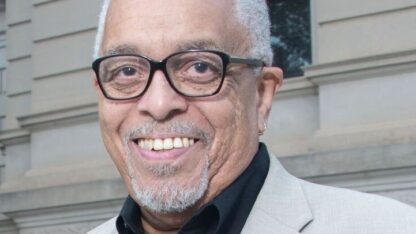

Ebony Love, seen here with her son Trejah, knows how hard it is to find an affordable home in the city of Atlanta.

Erin and Bryan Sintos for WABE

We often hear Atlanta is facing an affordable housing crisis. But it can be hard to understand how the city got to this point.

The issue isn’t simple. There isn’t one reason you can point to for the dwindling supply of low cost housing.

So in November WABE held a community event to highlight the complexity of the problem.

The event centered around the story of one woman, Ebony Love, and her search for a place her family could afford.

Ebony is from Atlanta. And so is her family.

Her mom is from the Old Fourth Ward and her dad is from a long since demolished neighborhood called Buttermilk Bottom.

In recent years, Ebony’s lived near the same intown places near where her parents have roots: Cabbagetown and Summerhill.

She likes living intown, because, in her words, it’s where life is happening. It’s also most convenient for her now that she has a son, Trejah.

Trejah is 10 now. He loves reading and always has.

Ebony says even when Trejah was two or three years old, she would find the TV’s caption turned on.

“I realized it was him,” Ebony says. “That was another way that he would read.”

But even though Trejah has excelled academically, Ebony long felt she’s had to homeschool him.

That’s because Trejah has a health condition: a type of epilepsy.

It’s probably not what you think of when you hear about epilepsy. Trejah has absence seizures. He’ll lose consciousness for like 10 or 15 seconds.

Ebony says they’re dangerous because they can happen at any time and sometimes he’ll have several back to back.

“He has to have someone watch him 24 hours a day,” Ebony says. “At any time he can have a seizure and walk into the street.”

Taking care of Trejah through these seizures has consumed Ebony’s life. She’s become a full time caregiver, and that’s meant she hasn’t been able to work.

But she’s found a way to make their life together possible.

Ebony got a housing voucher from the state. It helps pay for rent. And that helped her find a place at an apartment complex.

It’s at the very edge of Vine City, right next to the Georgia World Congress Center and Mercedes Benz stadium.

Ebony says they’ve started to have some stability here.

“I love the community. I love where we are right across from the train station you know is safe is gated. You know we have security,” Ebony says.

And the place is intown.

Again, being close to the center of the city has been good for Ebony now that she has Trejah.

That’s because it means being close to his doctors and grocery stores. She’s heard junk food is bad for seizures, so she’s really careful to get healthy food.

And being intown also means their family is close to something else: Trejah’s new school.

Ebony finally put Trejah on a waiting list at a charter school: Wesley International Academy, on Memorial Drive near downtown. And he got in.

“As he’s gotten older he wants to he want to try school. So this is one of the places that I’ve identified as a safe,” Ebony says.

She’s not positive the setup is going to work with Trejah’s seizures but a month and a half in Ebony says it’s going all right.

Getting Trejah in school was exciting for Ebony too. It could be a chance for her to get her life in order. Maybe she could think about working again.

Then, in April, something happened that put all of this into question. Ebony got a notice.

Her rent was going up. And it wasn’t a little increase. Her rent was going up from $800 a month to $1300 a month.

Ebony couldn’t afford the increase. Her voucher only paid up to $900 a month. So she knew she had to move.

But where is Ebony to move to? In the center of Atlanta, there are few if any units for under $900.

And Ebony also noticed that. She began to feel like she had just two options and she didn’t like either of them.

One was to move to outside the city. That’s a nonstarter for her, she says, since she just got her son in this school. Her car couldn’t can’t handle that commute.

The other option was to move into areas in the city that she calls the slums: substandard houses in neighborhoods with crime and trash.

Ebony didn’t think that was fair. She didn’t feel like she should be limited to those two options just because of her income.

“The world is made of people various different people. You need someone to shine your shoes. You need somebody to to bring you your food,” Ebony says. “We may not be able to have a stainless steel appliances but we don’t want appliances that don’t work.”

Ebony thinks everybody deserves decent, safe housing. So why is that so much to ask in Atlanta?

The WABE event highlighted the perspectives of several experts. Below are a few of the statements that were included in the presentation.

Georgia State professor Dan Immergluck pointed to the rising cost of housing in the city.

“We’ve been seeing rent increases in lots of neighborhoods that are 8 percent a year,” says Dan Immergluck, an urban studies professor at Georgia State University. “That’s a very steep increase when people’s incomes are going up at 1 percent a year. It’s really not sustainable for low and moderate income families.”

He says that’s partly because Atlanta is an attractive city, drawing higher income households and young professionals.

Meanwhile, Sarah Kirsch with a coalition called HouseATL — which recently provided affordability recommendations to the city — says Atlanta is creating a lot less housing than it used to.

“We were building on average 60 to 65 thousand homes a year for 20 to 30 years running taking out even the crazy bubble years,” Kirsch says. “And ever since the recession and even once we’ve returned to stable production, we’re producing about 30 thousand homes a year while being in the top three in the nation and job growth. It’s simple economics.”

A lot of the supply that is coming online is aimed at higher incomes. The industry site RentCafe found 90 percent of apartments construced last year were luxury units.

Chuck Young of Prestwick Companies says there is a big reason why developers are not building affordable housing: construction costs.

They’ve gone up in Atlanta and around the country. Young shared a scenario from last year.

“If I just went and bought a piece of property–there’s no parking deck or anything like that–just to raise the capital required to develop that property, you’re probably looking at between $1300 a month and $1350 a month,” Young says, “and that’s as cheap as you can deliver it.”

He says it costs more than a hundred dollars per square foot to build, which is double what it was ten years ago. And it’s only getting worse.

The event did highlight a few of the experts’ ideas for solutions. They included property tax breaks for landlords who agree to keep rents low, incentives for developers who focus on affordable units and a direct funding source for affordable housing through a tax on, say, parking.

As for Ebony, her search for housing did come to a happy conclusion.

She called every affordable housing property manager she could find. And finally she found a place in Edgewood. It’s by the MARTA train station, on a quiet block.

Ebony is amazed at how perfect the place is.

“I love this neighborhood. I love the street,” Ebony says. “My son has friends and they’re respectful kids. The neighbors are nice, everybody. This is like Sesame Street. It really is. Right now I can’t be in a better place. This is a real treat for us.”

Still, Ebony is a little nervous–that she might have to go through the housing search again one day.

Now she knows how hard it is to find a place she can afford. She knows how rare this place is.

If that day ever comes, when she has to move again, where will she go next?