Legendary Braves slugger Hank Aaron leaves legacy beyond baseball

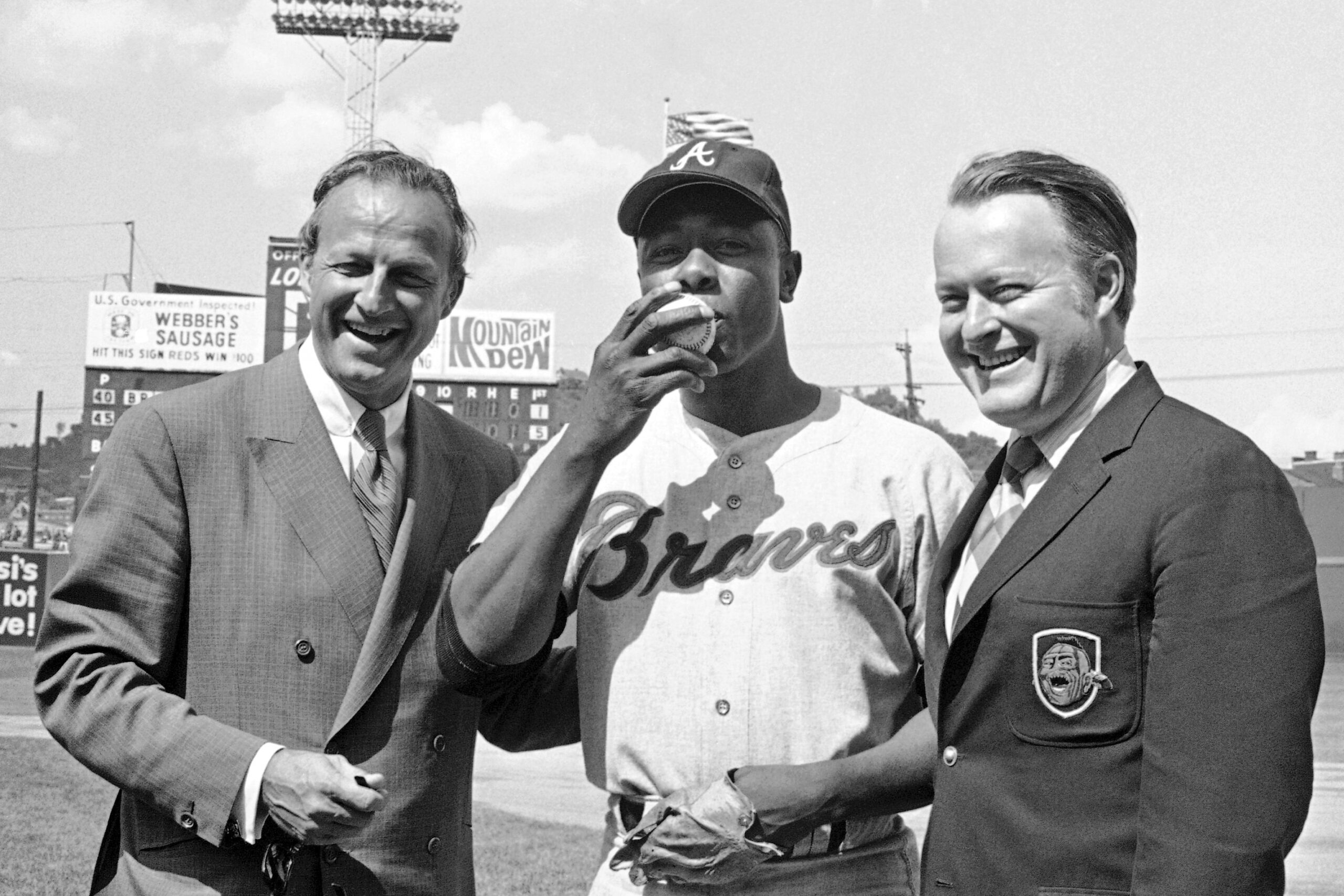

Atlanta Braves’ Hank Aaron, center, who became the ninth player in Major League history to get 3,000 hits, kisses a baseball alongside Famer Stan Musial and Braves owner Bill Bartholomay, in Cincinnati.

Gene Smith / Associated Press

Baseball legend Hank Aaron died Friday at the age of 86.

Aaron, a Black man, was one of the game’s most consistent sluggers, despite the racism that he faced throughout his time in the game – from his earliest days in the minor leagues to the biggest night of his career – to the night he became baseball’s all-time home run leader.

Henry Louis Aaron was born in 1934 in Mobile, Alabama, one of seven children. As a child, he remembered chopping wood with his father, looking up to see an airplane overhead, and aspiring to one day become a pilot. But his father had his doubts.

“Boy, you never will be able to fly an airplane, they ain’t gonna let you do that,” Aaron said in a 2016 interview with WABE’s Denis O’Hayer. “I said, well if I can’t fly an airplane, I want to play baseball. He said ‘neither one of those things you can do. Chop that wood, boy.’”

Aaron’s path to the big leagues started at age 15 playing semi-pro ball. He then had a brief stint in the Negro Leagues before he was signed by the Milwaukee Braves. Aaron was called up to the majors in 1954, where he became the Braves’ first Black player. He led the National League in hitting in only his third major league season and was the league’s most valuable player a year later.

He moved with the Braves to Atlanta in the mid-1960s and the home runs kept coming. As he moved closer to Babe Ruth’s all-time record of 714, he became the subject of racist death threats, leading up to April 8, 1974, when a sellout crowd was on hand to watch him and his teammates take on the Los Angeles Dodgers at Atlanta’s Fulton County Stadium.

Aaron sent a pitch soaring over the fence in left-center field into the Braves’ bullpen where Atlanta reliever Tom House caught the ball.

The crowd roared and fireworks exploded as Aaron rounded the bases and was met by his teammates — and his parents at home plate. Hall of Fame broadcaster Vin Scully described the scene.

“What a marvelous moment for baseball, what a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia, what a marvelous moment for the country and the world,” Scully said after several moments of letting the crowd roar. “Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol.”

And while Atlanta and the country celebrated, all Aaron could feel was relief.

“It was 2 ½ years, I’ve probably told this story many times,” Aaron said. “It was probably the saddest 2 ½ years I ever had in baseball myself.”

Aaron eventually hit 755 home runs — a record that stood for more than 30 years before it was broken by Barry Bonds. Aaron was inducted into Baseball’s Hall of Fame in 1982.

After his career, Aaron continued to make Atlanta his home and became a fixture in the community.

“Hank Aaron, he was a part of the Braves coming from Milwaukee to Atlanta to prove that we were a city too busy to hate,” said Atlanta native C.J. Stewart, who once played in the Chicago Cubs organization. He says Aaron was not only a transformative figure in the city’s history but was also a mentor.

“We can hold our heads up high, Black men, Black boys, Black people that love this game of baseball, know that he was a man that used this game to do a lot of amazing things,” said Stewart.

For his contributions to the game of baseball and to his community, George W. Bush game Aaron the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2002.

Friday, another president, Jimmy Carter was among those honoring Aaron. Carter called the baseball legend a “A breaker of records and racial barriers” whose “remarkable legacy will continue to inspire countless athletes and admirers for generations to come”