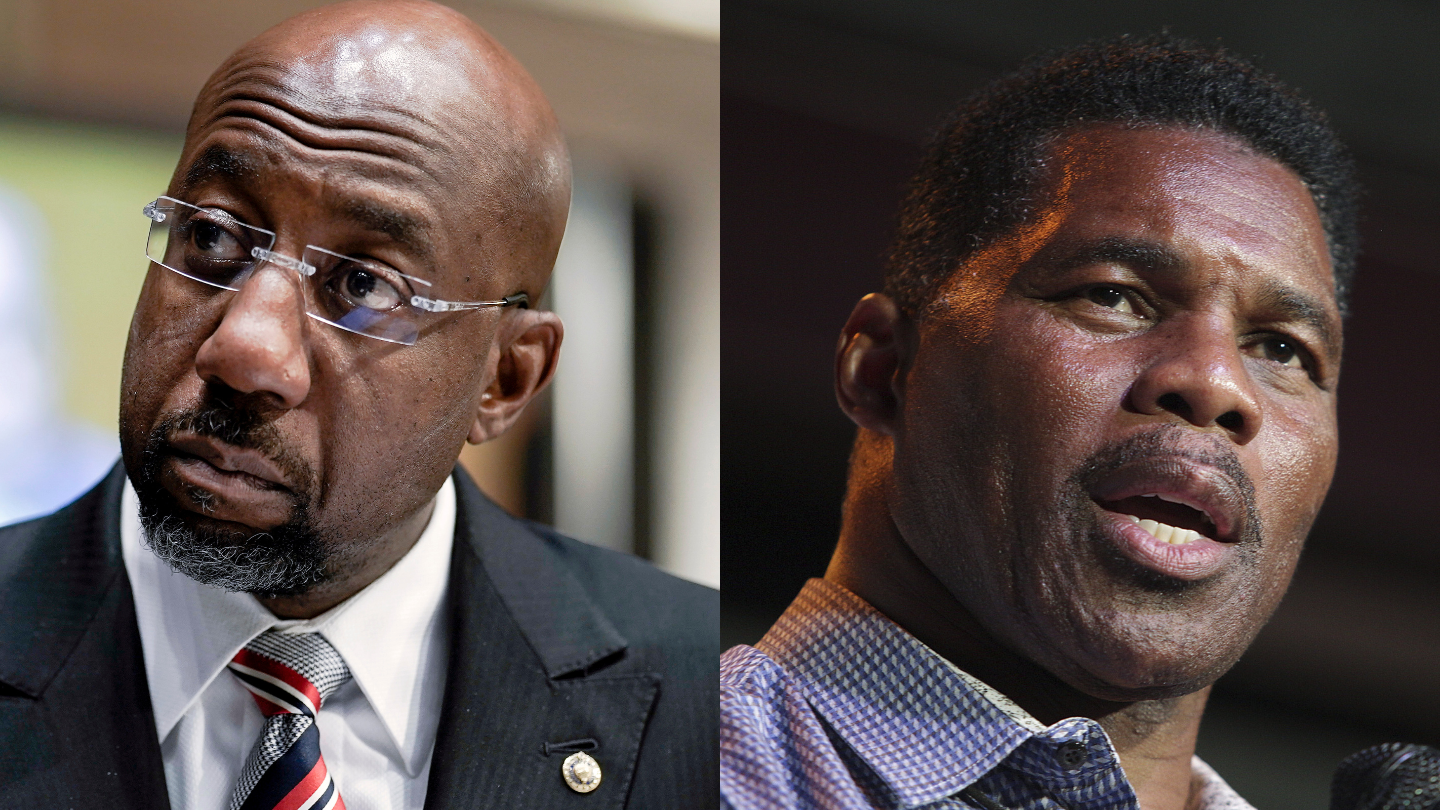

Black voters turned Georgia blue in 2020. Can Warnock and Walker appeal to them now?

U.S. Sen. Raphael Warnock and his opponent Herschel Walker have more in common than what meets the eye. Both are Black men that came from humble beginnings in Georgia, both are known as devout Christians and both are newcomers to electoral politics that embrace an identity as a not-so-typical politician.

Both men helped make history when they were nominated to run for Senate in this year’s midterm elections. It marked the third time in U.S. history that two Black candidates have run against each other for a Senate seat. Generally, it’s a rare occasion for two Black men to be on the ballot in any statewide election in Georgia.

Zooming out, Georgia has become a hotspot for national politics. It’s also a battleground state — the only Deep South state that voted blue in national elections in 2020 — with a shifting political landscape and a growing Black electorate. Also on this November’s ballot is an even more competitive race for governor.

The race between Warnock and Walker is one part of the nationwide struggle between Democrats and Republicans to control the U.S. Senate, which has major implications on federal legislation. The power to influence this election is in the hands of Black voters in Georgia. In the long term, it could be an indicator of how this key electorate will shape the trajectory of election outcomes in Georgia’s future.

The size of the Black electorate in Georgia has seen more growth than any other U.S. state, according to the Pew Research Center. Between 2000 and 2019, nearly half of the state’s increase in eligible voters were Black. As of 2019, 33% of the state’s total electorate were Black, totaling 2.5 million voters. Black voters originally from out-of-state were a major driver in this growth.

From 2016 to 2020, metro Atlanta, which aided in the victory of President Joe Biden in 2020, saw the highest percentage increase of newly eligible voters in the state. In 2020, over half of Georgia voters lived in metro Atlanta, which is home to 76% of eligible Black voters from out of state.

“It’s not just enough to say that oh, Black folks make up 33% electorate and assume that we’re all going to come out at that rate because if we’re not engaged, if we’re not energized, then that 33% can go down to 30 or 29.”

Cliff Albright, co-founder of Black Voters Matter

Georgia’s changing electoral makeup has coincided with its emergence as a battleground state. And Black voters were key to Democratic victories in 2020.

Black Americans make up a third of the state’s population but represented more than half of all Democratic voters in Georgia, according to 2020 exit polls. 88% of Black voters voted for Biden, who won by a narrow margin of 0.2%. It was the first time Georgia turned blue in nearly 30 years.

According to Politico, Fair Fight and the New Georgia Project, two organizations founded by gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams, registered more than 800,000 voters leading up to the 2020 election — many of whom were voters of color.

Warnock can credit his 2021 runoff election victory to Black voters, too. According to exit polls, he had 93% of the Black vote, and they were the majority of the coalition that elected him. In this year’s election between him and Walker, recent polling finds that he still has the support of the Black electorate.

Among Black voters in Georgia, Warnock is ahead of Walker 88% to 10% as of June 29. Among all Georgia voters, Warnock leads Walker 54% to 44%, marking the highest percentage difference since Walker announced his candidacy in 2021. Other polls have Warnock only slightly leading or even tied but rallying more Black voters could be critical for Walker.

At a Juneteenth celebration at the RNC Black American Community Center in College Park, Walker was asked about what he can do to make up the large difference in Black support versus Warnock. He told a reporter that recent polling numbers were incorrect, but went on to answer the question.

“What I can do is continue to get out to meet the people, continue to do things like this right here and show that policies here doesn’t really work with a lot of Black and Brown people,” he said.

Walker on Black support

‘Demographics isn’t destiny’

Cliff Albright is the co-founder of Black Voters Matter, an Atlanta-based organization focused on voting rights and community empowerment. He says that Black voters were critical in deciding Democratic primaries and are increasingly important in statewide elections. But because this voting group holds so much power, election subversion is something Black voters should worry about, he says.

When Biden won the presidency in 2020, Georgia became the focus of former President Donald Trump’s attempt to overturn the election results.

Albright says that Georgia had a critical role in what led to the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, and it’ll continue to be part of the discussion in this election cycle.

“Part of what they were trying to overturn wasn’t just the national election, but it was specifically votes in certain states, including Georgia, where what they were really saying is that these Black votes shouldn’t count,” he says.

Voter suppression and intimidation could also be a factor since the passing of SB 202, says Albright. Passed in March 2021 as a response to the 2020 election, the Republican-led law overhauled elections in Georgia. It imposed tighter requirements on absentee voters, reduced the number of ballot drop boxes, gave new power to the State Elections Board and stripped power from the secretary of state, among other things.

After the law was passed, the U.S. Department of Justice filed a lawsuit against the state of Georgia alleging that the law was racially discriminatory.

Election data also shows absentee ballot rejections disproportionately affect Black voters. In this year’s May 24 primary, 30% of absentee ballots were cast by Black voters. Black voters were the second-largest share of voters that used absentee ballots, yet they had a higher percentage of rejected ballots compared to white voters, who made up the greatest share of absentee votes.

Another potential barrier is disinformation, which Albright says is targeted at young Black people and Black men particularly. Candidates or parties can purposefully spread inaccurate information for their own gain.

In the face of different factors that can discourage people from voting, he says we shouldn’t expect a high turnout just because voter registration is growing.

“This new demographic of the power of the rising Black votes and brown votes … we’ve got the power to make a difference in these elections,” Albright says. “But demographics isn’t destiny. It’s not just enough to say that oh, Black folks make up 33% electorate and assume that we’re all going to come out at that rate because if we’re not engaged, if we’re not energized, then that 33% can go down to 30 or 29.”

Voter engagement efforts by organizations such as Black Voters Matter are what produce high voter turnout, he says.

Still, it’s the first time many Black Georgians will vote in a general election race with multiple Black candidates to choose from. And although it’s not a factor in this race, Albright rejects the idea that Black voters have ever had race loyalty when voting for a candidate. Race loyalty occurs if a Black voter were to vote for a Black candidate simply because they share the same racial background, for example.

“We are nuanced enough to recognize that the basis of our vote isn’t going to just be about skin color and race,” he says. “It’s going to be about where folks stand on the issues that are important to our community. And that’s what’s going to define the way that Black folks vote in this election in Georgia.”

But party loyalty is more common, he says. Though historically, Black voters overwhelmingly vote Democratic, Albright doesn’t support the “blue no matter who” stance that he says some voting rights organizations take. This line of thinking puts less emphasis on the issues at hand.

“When you’ve got that perspective, then you can’t hold anybody accountable because the only thing on which you were mobilizing was just off of a party or off of an individual,” she says.

Connecting with Black voters

With no prior political experience, Walker is relying on his life experiences to resonate with voters.

The reputation he earned as a UGA football player means he’s already known and respected by many Georgians. Republican strategist Julianne Thompson credits his primary win to name recognition, which could win more votes in November.

“[Voters] love his sports background, and I think that that sports background is going to attract a lot of people that perhaps do not traditionally vote Republican,” she says.

Walker and his campaign are branding him as someone who’s not a typical politician — and isn’t trying to be. Thompson said that this has helped him connect with voters because they feel they can relate to him.

“He’s somebody fresh and different in the political scene and they’re excited about him and they’re excited about what he brings to the table as far as excitement and motivation, especially of young males who are so interested in sports,” she says.

Walker grew up in Wrightsville, Georgia, a small town in rural Georgia. Reflecting on his own journey from humble beginnings to achieving success is an important part of his campaign and a reason why he resonates so well with “regular people,” Thompson says.

Warnock, a freshman elected official, has a similar “rags to riches” life story that he’s used to his advantage — he grew up as one of 12 siblings living in public housing in Savannah. But with a full year as a senator under his belt, his campaign is focused on touting his political record.

“From fighting to expand Medicaid and pushing to forgive student loans to making prescription drugs affordable and addressing the maternal mortality crisis, our campaign is going to communicate with all Georgia voters, including Black voters across the state, about Rev. Warnock’s record of fighting for hardworking Georgia families,” said Warnock’s campaign manager Quentin Fulks.

Warnock’s role as a pastor at Martin Luther King Jr.’s Ebenezer Baptist Church will help him connect with Black voters, says election forecaster Niles Francis, especially concerning his understanding of race issues. Polling shows that for Black voters, racial inequality is among the top issues that they are most concerned about.

When it comes to campaign strategy, Francis believes it’s in Walker’s best interest to distance himself from Trump. (Trump has endorsed Walker, but Walker has denied that Trump is the reason he’s running for office.) Trump-backed candidates suffered big losses in May’s Republican primaries.

“If I were him, I would try to avoid having [former] President Trump come to Georgia and hold rallies because he’s not popular here,” he says. “We saw this in the primary … he still has that segment of voters who love him, but at the same time, many Republican voters are just ready to move on.”

In the opposing camp, Warnock should distance himself from President Biden, Francis says. Polling shows that 33% of Georgia voters approve of Biden’s performance in office. Among those who disapprove, 81% support Walker, according to separate polling from early June.

This would be a shift in how the GOP attacks Warnock. Francis recalls that in 2020, when former Sen. Kelly Loeffler was campaigning against Warnock, they launched repeated attacks against his sermons and church. Francis says that “pissed off” a lot of Black voters and backfired.

On June 30, Axios reported that Chris Hartline, communications director for the National Republican Senatorial Committee, acknowledged that their attempts to portray Warnock as a radical, liberal socialist “didn’t cut through.” Now, the NRSC is reportedly focusing on aligning Warnock with Biden, who has become an easy target for Republicans to blame for “kitchen table” issues like inflation and gas prices.

Among Black voters, 54% approve of Biden’s job performance, creating a significant opening for Walker’s campaign. And they’re already one step ahead with this messaging.

“It’s been 505 days since Warnock was sworn into office, and he has done nothing besides serve as a rubber stamp to Biden’s agenda and run our economy to the ground,” Walker campaign spokesperson Mallory Blount said in a statement.

Despite the use of campaign tactics to influence voters — and perhaps for that exact reason — many people are fatigued by the seemingly neverending election cycle in Georgia. Francis is expecting some Black voters to abstain this year.

“I am one of those voters that are exhausted, especially living in a swing state,” Francis says. “It’s just an election after election after election. And it’s not just Black voters. Many voters in general are tired of having to be the subject of millions of dollars in negative ads, having two candidates showing up in their email inboxes asking them for money and things like that.”

“But at the same time, many Black voters know and understand how important the right to vote is … people like John Lewis, Martin Luther King and Jesse Jackson … Civil Rights leaders like that were beaten and jailed and almost killed for the right to vote and they know that the right to vote is too precious to just not take advantage of it,” he says.

This November, the race between Warnock and Walker will show whether recent events that have put democracy into question — like the Jan. 6 insurrection and the passage of controversial election laws — will energize or discourage voters in a pivotal election.

The growing Black electorate has already proven to be a key voter group for deciding elections in Georgia. This year, these two Black candidates’ ability to gain Black votes will be critical in deciding this election that will have impacts that reverberate through the U.S.

Rahul Bali contributed to reporting this story.