Changes in Coastal Georgia DA's sex crime prosecutions worry victims, attorneys

In November 2020, Sarah Harper, a Savannah hairstylist, was sexually assaulted during a date. Initially, her fraught decision to go to the authorities was rewarded. Within a month, her assailant was arrested, and three months later he was indicted on charges of kidnapping and attempted rape.

The efficient pace of prosecuting sex crimes cases was something the Chatham County district attorney’s office had long been lauded for. One highlight was a cooperative system of victims’ rights advocates, social services and specialized attorneys meant that abused women and children often received proactive and sympathetic care. But that changed after December 2021, the last time that the DA’s office held a multi-agency meeting meant to achieve the best results for sex crime victims, according to an investigation by The Current.

This is one of several changes instituted under DA Shalena Cook Jones’ tenure that have defense attorneys, sexual abuse advocates and former prosecutors worried about the level of care and expertise for survivors of traumatic sex crimes.

For the first time in approximately two decades, the Chatham County District Attorney’s office does not have a Special Victims Unit, a hallmark of most American prosecutorial offices where attorneys are specially trained and only prosecute cases of sexual assault, child abuse, elder abuse and intimate partner violence.

From January 2021 — when Cook Jones started as DA — to the end of 2023 at least 36 prosecutors have left the agency, according to a review of staff lists. Of those, 22% were SVU prosecutors.

In Harper’s case, staffing upheavals meant she had to contend with a revolving door of prosecutors and victims’ advocates during her more than two-year legal case. Although the man who pleaded guilty to attempting to kidnap and rape her has violated the terms of his plea deal, there is no urgency, she says, to put him back behind bars.

“I haven’t had a chance to even process what happened to me,” Harper said, “I’m still dealing with the residual effects of my time being stolen, because I have to hunt down information that should be given to me anyways.”

Cook Jones rejects the criticism that her office is less equipped to handle SVU cases than her predecessors’. She says she worked diligently to clear dozens of inherited sex crimes that were “gathering dust” under the prior DA.

According to court statistics, Cook Jones’ office closed 162 felony sex crime cases between Jan. 1, 2021 and Dec. 31, 2023, her first three years in office. Heap’s office closed 126 such cases in the last three years of her tenure. “Closed” can mean the result was a conviction, guilty plea or dismissal.

Due to the exodus of experienced attorneys and a dismal job market for quality lawyers, Cook Jones said she has trained all her prosecutors to take on major crime cases, without specializing into units. She says the shift is beneficial. Siloed veteran prosecutors can have rigid ideas about sentencing, which can be inequitable, she said.

She concedes, however, that her office could use more funding from the county to support sexual assault survivors.

“The victims of serious violent crime are our highest priority, I wouldn’t be in this line of work if that were not the case,” said Cook Jones, a former SVU prosecutor who specialized in elder abuse cases. “But in order to make that a reality, we have to reallocate our resources so that we are focusing on the crimes that matter most.”

History of victim advocacy

The Chatham DA’s office was once a statewide leader for victim’s advocacy. In 1983, former DA Spencer Lawton, of “Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil” fame, established Georgia’s first-ever victim/witness assistance program, according to Lawton.

Former DA Meg Heap got her legal start interning for that program and then working as a victim’s advocate. Elected DA in 2012, she made prosecuting sexual violence and championing victims’ rights central pillars of the agency. The SVU was staffed with six attorneys when she left office after losing her 2020 re-election bid to Cook Jones.

Between the changeover from Heap to Cook Jones, several services related to crime victims and best practices involving SVU prosecutors were stopped, forgotten or dropped. Supporters of Cook Jones say that is in part due to a lack of detailed succession plan by her predecessor. Detractors of the current DA blame her mismanagement.

The change of leadership did affect how the office received funding for SVU victims’ advocacy.

Between April 2018 and December 2020, Heap received close to $100,000 in state funding from the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council for prosecution and victims’ support

But Heap’s office did not apply for those funds to continue into 2021, minutes from the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council meeting show.

That left a hole in Cook Jones’ victims’ support budget as she started her tenure. She did not re-apply for that bucket of funding, according to the CJCC.

Instead, her office took advantage of federal funds for victim advocates, as well as funds from the Prosecuting Attorneys’ Council of Georgia.

Cook Jones said she plans to ask Chatham County commissioners to fund more victim advocates in the upcoming budget.

Turnover withers institutional knowledge

As of January 2024, none of the six SVU prosecutors who worked under Heap remain employed at the DA’s office.

One former SVU prosecutor told The Current, on the condition of anonymity as not to affect their current position, that attorneys in the DA’s office had to take on more felony cases as more prosecutors resigned, leaving less time to focus on SVU cases.

Within a specialized SVU unit, a prosecutor generally would be involved in a sex crimes case from the first days to a hoped-for conviction. Their knowledge of key evidentiary hurdles means they are alert to preserving sexual assault kits, phone records and police reports. They also establish a rapport with the sexual assault survivor to shepherd them through an often grueling process. Since 2022, there was less and less time to build that relationship, the prosecutor said.

The turnover of SVU attorneys meant that no one remained at the DA’s office to act as point person for Sexual Assault Response Team (SART) meetings, the interagency group that victims’ advocates and former SVU prosecutors say was an important piece of the sexual violence support apparatus in Chatham County.

Those meetings became a central hub where police, victim advocates and social services could share information in support of survivors and the prosecution of their cases, said Doris Williams, the executive director of Mary’s Place, who participated in those quarterly meetings.

“We’re able to lean on each other, or reach out to one another and say, ‘Hey, do you have this resource? Can you help me with this?’” Williams said. “And that connection, it’s a ripple effect. It builds a stronger community and it supports the citizens in a different way.”

All of this helped survivors motivated to go through the courts (some choose not to, Williams noted) withstand the system and see the crime punished.

According to Williams, SART members plan to restart the meetings in February 2024.

Victim feels caught in chaos

The tumult within the DA’s office was just starting when Harper, the hairstylist, experienced the most traumatic evening of her life. She says it has adversely affected her.

Harper spent three days in a haze after her Nov. 19, 2020 date with Antonio Castellano.

Harper, 41, who worked as a bartender and hairstylist, met Castellano in downtown Savannah at around 6:45 p.m.

At the time, Harper, a blunt yet boisterous person, had not been on a date in two years and felt nervous. Castellano comforted her, she said.

Castellano later offered to drive her home; she accepted. Harper’s internal alarm bells began to ring when he drove past the turn-off to her house.

Castellano took her onto Ogeechee Road and then into a dark cemetery, before sexually assaulting her in the car, according to court documents

For the next few days, she wasn’t sure what to do. A friend convinced her to contact what was then known as the Rape Crisis Center, now renamed Mary’s Place. After doing that, she filed a police report.

Harper finally spoke to a police officer four days after the assault. The detective took her statement but wasn’t able to download her phone data into evidence. He told Harper that it was too late for a sexual assault kit to gather physical evidence (The SART guidebook says that examinations can be conducted from five days to a week after an assault).

Castellano was arrested by Savannah Police in December 2020 and indicted in March 2021.

Harper said she was unsatisfied with the victim advocate assigned to her case. She said she found out about her assailant’s bond hearings from the police, rather than the DA’s office.

The DA’s office transferred her to the care of Cheryl Jones, director of Victim/Witness Assistance Program, in April 2021, text messages show.

Jones was kind and helpful, according to Harper. But in June 2021, Jones texted her that she was retiring, and Harper would be transferred back to her original advocate.

By the start of 2022, Harper’s case had been assigned to three separate prosecutors — all of whom resigned from the DA’s office — and three victim advocates.

Harper said she had trouble getting basic information about the case status from the DA’s office.

She also said she was never provided the Crime Victim’s Bill of Rights by the DA’s office, required under Georgia law. The document states survivors have the right to be kept up to date on “court proceedings or any changes to such proceedings” and seek compensation through the Georgia Crime Victims Fund.

“It’s a lack of transparent information to understand the process,” Harper said, “Why do they have the right to decide if I get to feel safe after being violated?”

At the same time, the detective who originally took her statement had been removed from her case. (Savannah Police Detective Vincent Miller was arrested by state police for child abuse in May 2021; that case is still open). Harper wasn’t notified.

By March 2022, Castellano’s case was headed to trial. Harper, by that time, knew that her assailant had previously been convicted of sexual assault. She says her victim’s advocate was slow to answer her questions about whether those records would be included in trial.

Her frustration boiled over in conversations with friends. “I haven’t even spoke to the (prosecutor),” Harper texted a friend, “Just hate feeling left in the dark.”

In April 2022, Castellano decided to plead guilty. Harper sent in her impact statement, a standard for crime victims who want to have their say at a sentencing hearing.

The victim advocate called Harper and told her prosecutors were going to offer him a plea deal with five years in prison. The deal changed to two years by the time she arrived in court, Harper said.

Castellano pleaded guilty to one count of kidnapping, one count of sexual battery (reduced down from aggravated sexual battery), and one count of criminal attempt to rape. He was sentenced to two years in prison, with 18 to serve should he violate probation. He was required to register as a sex offender, not allowed to leave the state without permission, banned from Chatham County, social media and dating apps, and ordered to not contact Harper.

Harper said that the prosecutor at the time, Donna Sims, told her the punishment was weak because the case was weak in evidence: Her phone data was never authenticated, the case’s detective was indicted and removed, and she never had a sexual assault kit completed.

Sims left her job at the end of 2022 and now works at a different county’s DA’s office.

Castellano was released from prison after approximately eight months. As of September 2023, he had violated three probation rules, according to court documents.

In November, a new prosecutor was assigned to handle the probation violations. A hearing to revoke probation has been rescheduled three times and is currently set for May 2024.

Cook Jones defended her office’s handling of Harper’s case. The DA also said her office is partnering more closely with Savannah Police and Chatham County Police to ensure more thorough case investigations in order to help prosecution.

She respects that some victims may be unhappy with the way the judicial system works. However, “does that mean that our office is not effective? Absolutely not,” the DA added.

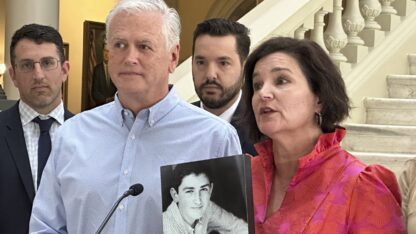

Harper said she wishes her saga could end but feels strongly about advocating for sexual assault survivors. Last spring, she attended a bill-signing at the Chatham County Sheriff’s Office by Republican Gov. Brian Kemp for a prosecutor oversight bill. While the oversight committee is currently in flux, she says holding district attorneys and victim advocates accountable is a nonpartisan issue for her.

“I am not Republican or Democrat. I don’t care about that. This is a bipartisan issue. This is an issue for all. Mother, daughter, sister, child, cousin, grandma, best friend. I don’t care,” she said. “Try to go through that yourself with having to hunt down information and waste your life and have it kill your business. And just watch no justice be served for the innocent.”

This story was provided by WABE content sharing partner The Current.