Closing The Gap: How Georgia Plans To Produce More High School Graduates — Part 1

Johnson supports and guides her students, but she also helps them with coursework when they get stuck. Here, she’s helping Alexis Darks with a math assignment.

BITA HONARVAR / For WABE

Earning a high school diploma boosts a person’s earning potential and decreases that person’s chances of living in poverty. Georgia is making progress in that area.

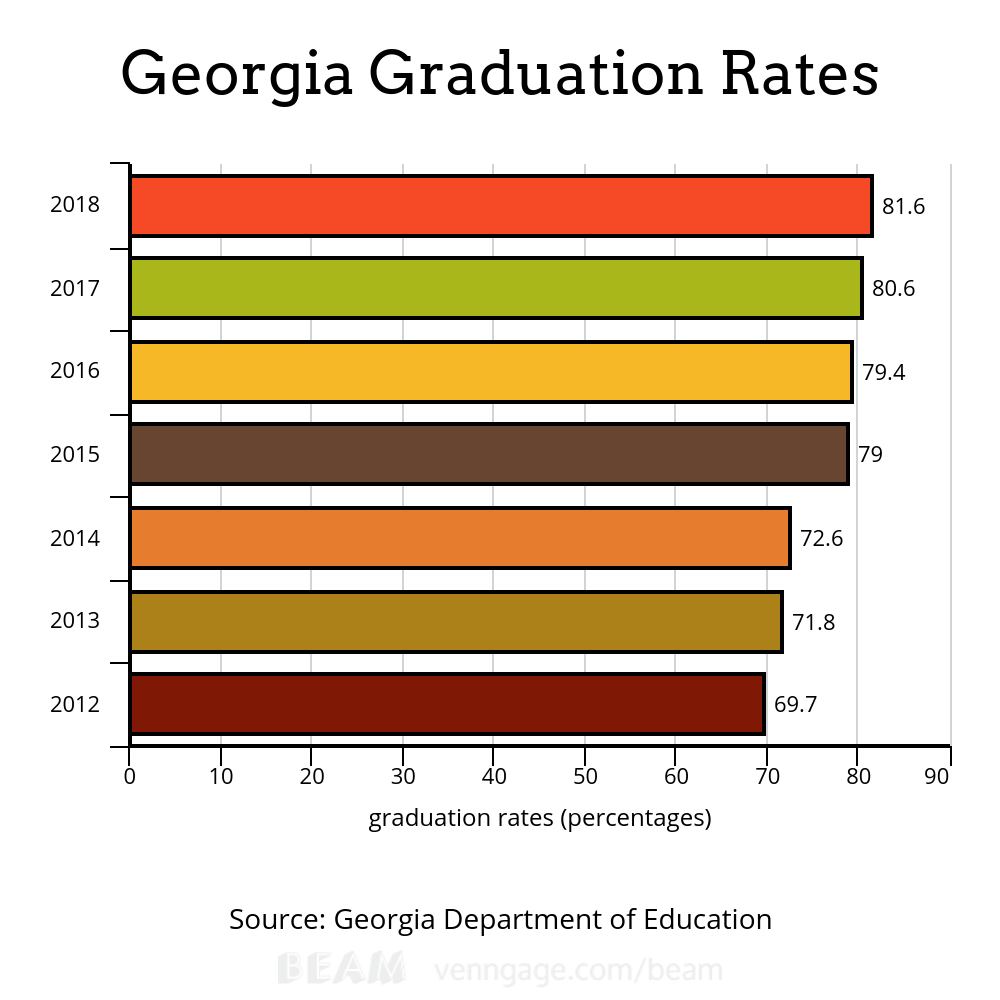

Last spring, the state’s high school graduation rate reached an all-time high of 81.6 percent. The rate includes students who started a Georgia high school in the fall of 2014 and graduated in the spring of 2018. It also includes students who transferred in. It doesn’t include students who take more time to graduate or those who’ve moved to other states and can’t be tracked. However, the number shows almost one in five Georgia high school students didn’t graduate on time last spring.

School leaders have made several efforts to intervene over the years. In 2006, then-governor Sonny Perdue put money in the state budget so that high schools could hire graduation coaches. A study showed the program was effective, but austerity cuts led most districts to eliminate the program.

A nonprofit group called Communities in Schools oversaw the graduation coach program. The organization’s mission has always been to intervene with students at risk of dropping out and helping them finish high school. CIS was founded in Atlanta in 1977. It partners with schools all over the state. CIS hires coaches and mentors to work with students on what the organization calls the ‘ABC’s’: attendance, behavior, and coursework. Usually, students who struggle in at least one of those areas are considered ‘at risk’ of dropping out of school.

Re-Learning The ABCs

Jessica Johnson is a CIS student support coach at Atlanta’s Washington High School. She occupies a classroom on the historic school’s first floor. One Wednesday morning, a group of students has come to visit her in between classes. She senses that they’re dawdling and asks them what they need. One student speaks up, saying she’s thirsty.

“You’re thirsty?” She asks. “Everybody’s thirsty?”

They all say ‘yes,’ as Johnson reaches under her desk to grab some bottles of water. She hands them out and sends the students to class.

More than 70 percent of Washington students come from low-income homes. Johnson’s job is to help them stay on track academically and provide emotional support. She says that sometimes means making sure their basic needs are met.

“If they’re hungry, I’m going to make sure that they eat, but also, while they’re eating, I’m like, ‘Ok, so what classes do we need to make up?’” Johnson says. “’I need you to make sure your attendance is on-point. I need you to make sure we don’t have any additional behavior infractions.’”

Johnson is assigned certain students to work with. They come to her room during free periods to work on assignments. Johnson stays on top of them about their grades. Junior Alexis Darks is one of them. She says she struggles in school sometimes.

“I’m not a visual learner,” Darks says. “I can’t just look at the board and get it. I have to have a one-on-one sometimes. And teachers, they might not take it too well. They’ll think I’m not paying attention or listening.”

If I can just get them to come to school every day, we can work on everything else.

Jessica Johnson, CIS student support coach at Washington High School

Last year, Darks didn’t really like coming to school, so she missed a lot. Her grades suffered. Things weren’t going well at home either, so when she did come to school, she got in fights with other students. That resulted in suspensions. Then Johnson intervened.

“[Ms. Johnson] came in, she be like, ‘Look, you’re too close to graduating, you can’t keep doing it,’” Darks says. “I finally grasped it. I’m like, ‘You’re right.’”

Johnson remembers it differently.

“She’s being modest,” Johnson says. “I stalked her. I would hunt her down in the hallway, like, ‘I’m here. Utilize me. Whatever you’re going through, hey, you can talk to me about anything.’ I believe in praising them when they do good, but they know I’m going to get on them when they’re off track.”

Johnson says Darks’ grades and attendance have improved this year. She expects her to graduate on time next year. Afterward, Darks wants to go to Atlanta Metropolitan College and study cosmetology.

“All It Takes Is One”

Experts say mentors like Johnson are often the key to keeping at-risk kids in school.

Jen Packard is a licensed clinical social worker with CHRIS 180, an organization that provides mental health services for schools and training for teachers. She says kids who beat the odds of having rough home–or school–lives are often resilient. And that resiliency, she says, often comes from building strong relationships.

“Attachment Theory and Resiliency Science show is all it takes is one attuned caring adult in your life to really shift what’s capable for you,” Packard said. “That’s the roots of resiliency. And if you’re not getting it home you can get it from a teacher. You can get it from a coach a mentor.”

Packard says we’ve all experienced some kind of trauma that can interfere with—for example—school performance. The question is often whether it’s trauma with a ‘big T’ or a ‘little t,’ she says.

“In the field we talk about ‘Big T’ traumas of neglect, sexual abuse, physical abuse, witnessing domestic violence, experiencing domestic violence, war, terrorism, medical trauma accidents,” she says. “Those are considered ‘big traumas.’”

The ‘little t’ traumas are more common, Packard says.

“Every human being as has experienced a ‘little t’ throughout their life: moments of disruption, moments of disappointment, grief and loss, divorce, changing of caregivers,” she says. “So trauma really doesn’t discriminate.”

The bigger the trauma, the tougher it can be to focus on something like earning a high school diploma. But for Imoni Stinson, a junior at Washington, just spending time around Jessica Johnson makes a difference.

“When I feel like I don’t want to be around nobody, I come [to her classroom] sometimes,” Stinson says. “I sit at the computer and do my work.”

Stinson says she likes school, for the most part.

“It kind of do help me when I’m going through stuff at home because I don’t like being home sometimes,” she says quietly.

Stinson’s favorite subject is literature, even though she wishes her teacher weren’t so demanding. That’s where Johnson can step in–not to get a teacher to ease up–but to make sure her students know what’s asked of them.

“I’m like, ‘OK. Get your work. If you don’t understand it, I’ll go to the teacher and ask for clarification.’”

A Beginning, Not an End

Johnson says making sure her students complete their assignments isn’t her biggest challenge.

“If I can just get them to come to school every day then we can work on everything else,” she says. “They’ve shared a lot of personal stories with me. And like I said before they know this is no judgment. They know that I love them. They know that I care about them. They know that I’ll advocate for them and then I’ll fight for them.”

Her students are aware of her fierce devotion to them. They have her cell phone number, and Johnson says they’re welcome to call her anytime, and they often do.

Deanna Norman, also a junior, says she likes U.S. History and math, but Johnson is her favorite part of school.

“It’s her personality,” Norman says. “It’s like when I’m at school, it’s like a second home.”

Norman, Stinson and Darks all plan to go to college after graduation. Johnson plans to keep tabs on them to make sure they do. She wants all of her students to see walking across the stage to get their diplomas as the beginning and not the end. This kind of dedication could be one reason why CIS has such a high success rate. During the 2017-18 school year, 95 percent of K-11 students in the program were promoted to the next grade, and 96 percent of twelfth graders earned a high school diploma or GED.

Read Part 2 of the series here

Read Part 3 of the series here