Critics of Georgia’s new 'divisive concepts' law say it could cause confusion

Corinthia Howard Knight teaches her ninth-grade American Government students about Georgia’s new “divisive concepts” law. (Kaitlin Kolarik)

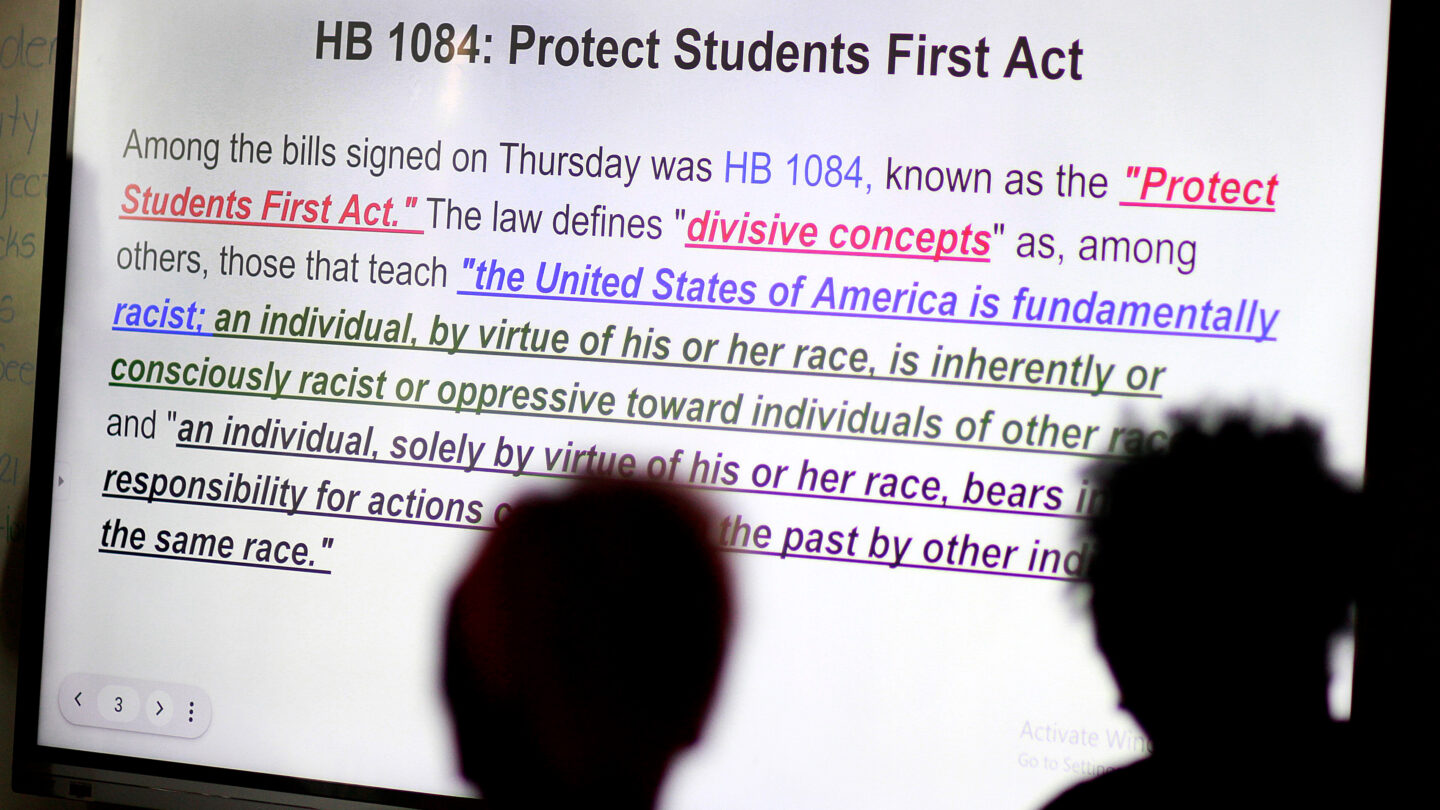

As Georgia public schools resume classes, they have new laws to follow this year. One of them, House Bill 1084, bans educators from teaching so-called “divisive concepts.” The law’s critics say the language is vague, which is likely to cause confusion among educators.

HB 1084 bans nine concepts. Some are straightforward. For example, teachers can’t say one race is superior to another. Others are more controversial: educators can’t teach that the U.S. is fundamentally racist. Brock Boone, an attorney with the Southern Poverty Law Center, says that language is unclear.

“Whenever laws are vague and confusing, and teachers and educators face fear of violating something, it has the result of silencing speech,” he says.

The law’s supporters say it doesn’t prevent teachers from accurately teaching historical events, like the Holocaust or slavery. It also says the law shouldn’t interfere with fully implementing Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate curricula. But Boone says there could be a “chill effect,” where teachers don’t elaborate on the root causes of an event or conflict for fear of breaking the law.

“Where this law comes into play is if a student asked any potential follow-up question like, ‘Why did this happen?’’ he says. “Or ‘What does this mean for our country? Why did we do something so terrible?’ That is where educators have the potential of violating this classroom censorship law.”

Lawmakers considered a House and Senate version of the bill during the 2022 legislative session. Most Democrats opposed the measure, saying it wasn’t needed. Sen. Nan Orrock, D-Atlanta, questioned Republican Sen. Bo Hatchett, R-Clarkesville, who sponsored the Senate version of the bill.

“I’d love your answer to telling us where these practices are occurring now in our school system that requires this massive bill that is being circulated around the country by members of your party in state after state,” she said. “Where’s the example in Georgia? What is it that we’re trying to stop? Have we got a problem that this is solving? Do we have any evidence that this is occurring in our schools?”

Hatchett admitted he didn’t hear complaints about teachers covering the banned topics.

“To your point, 99.99% of Georgia teachers would not teach these divisive concepts,” Hatchett replied. “That’s been one of the biggest questions that I’ve gotten is, ‘Where is the proof? Where do you see this?’ But, I’ll tell you one of the things that was shocking and alarming to me throughout this process based on internet emails, comments on social media, is there are people who criticize this bill and say that these divisive concepts should be taught.”

Hatchett said the bill would prevent a problem from developing as opposed to addressing an existing problem.

But Boone, with the SPLC, says because the law’s language is hard to understand, it could end up confusing parents and teachers.

“Where do you draw the lines between discussion and advocacy?” he says. “It is very possible that a potential teacher who is simply teaching facts or teaching what happened could be seen by some parents or some teachers, or by some students … [who say] ‘I think that teacher’s advocating, not just teaching.’”

Sixteen states have passed similar laws. Georgia’s law requires every school district to adopt a complaint resolution process. That could result in more work for school principals. They’re required to investigate complaints within five school days, decide if a violation took place and inform parents of any action within ten days.