It seems ludicrous that in the state of Tennessee, there are more monuments to a slave trader and grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan than to all three of the state’s presidents combined.

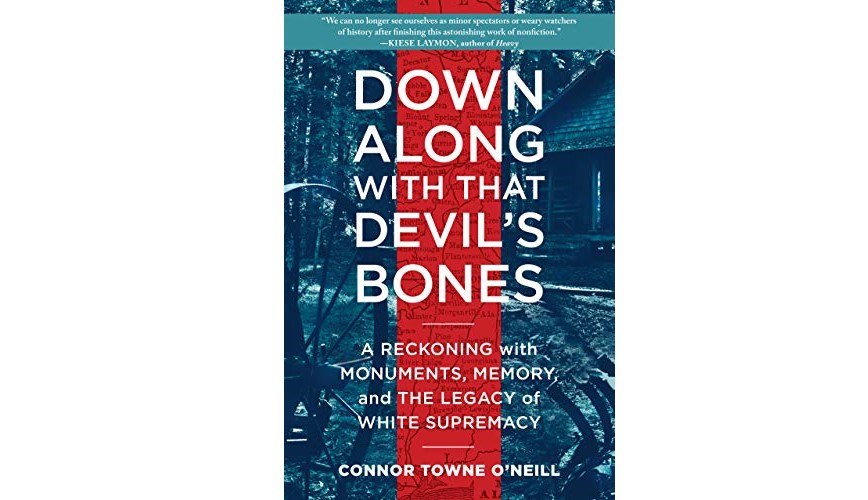

Yet, the tributes to Confederate Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest can be found throughout the South. This was the inspiration behind Connor Towne O’ Neill’s new book “Down Along With That Devil’s Bones: A Reckoning with Monuments, Memory, and The Legacy of White Supremacy.”

“City Lights” host Lois Reitzes spoke with O’ Neill about this essential anti-racist reading.

The Atlanta History Center will be hosting a virtual event with O’Neil on Oct. 27 at 7 p.m. He will be in conversation with Anthony Knight, founder and CEO of The Baton Foundation.

Interview Highlights:

How producing the NPR podcast “White Lies” helped inform his book:

“In the most basic way, it was what was bringing me to Selma a lot and how I stumbled upon this story. When I met this Neo-Confederate group in the cemetery [just a few blocks from the Edmund Pettus Bridge], they handed me a stack of Confederate propaganda that included a letter that outlined the conspiracy theory about how the civil rights movement had killed James Reeb. And we spent a lot of time in the podcast really deconstructing and decimating that conspiracy theory. It was of course the theory that the defense attorney used to lead to the acquittal of the men accused of killing Reeb. The book is kind of a spin-off of some of the reporting we were doing on ‘White Lies.’”

How the monuments are a representation of those who wanted them created in the first place:

“The monuments of the places that we live can sort of fade into the background of the skyline, and it’s easy to think of them as always having been there. They were put up in a particular moment. Especially if they’re on public property, putting them up would require a certain economic power and certainly political power as well. Obviously, they seek to remember someone from the past, but you can’t just put up a monument, it does require some exertion of power. In exerting that power, you’re deciding for a town, a city, a state, a university, who’s worthy of being remembered in the moment you’re remembering them. Not everyone gets a monument. So you can look at the landscape and think, ‘Who gets remembered and when are they being remembered?’ as a reflection of those values of the society in the moments in the present.”

The debate around Confederate monuments:

“Confederate monuments tell us that we don’t need to change. That when we look backwards we should see things that flatter us and don’t hold us accountable or responsible, but instead say, ‘Yes, our past flatters us’ and this is American Exceptionalism 101 in a lot of ways. So if you ask people why they want a statue of Forrest to stay up, they say, ‘Well because he was a great military commander or because he was a self-made man.’ And the sort of magical thinking required to only think about Forrest in those terms I think is really seductive. I think in one way or another it’s seductive for lots of people regardless of their feelings about Forrest specifically. I think we’ve inherited a drastically, unequal, violent, morally bankrupt society. Thinking about the past and the ways that the system of slavery was spiritual and physical torture and essentially built the modern economy, enriched people in the North as well as the South. The lie that people in the North and the South were telling to justify that system … and so if you look at the past and see that we should be held accountable to that past, then we need to change.”